Prisoners of the North (13 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

A group of Copper Eskimos whom Stefansson discovered on Victoria Island

.

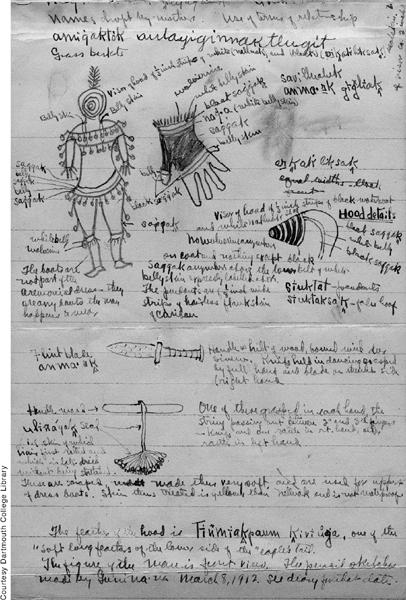

A page from Stefansson’s diary, March 1912

.

In his book

My Life with the Eskimo

, Stefansson devoted a whole chapter—5,100 words—to the subject, using literary, scientific, and historical references to support his conviction that this

might

be a unique band descended from survivors of the long-gone Greenland colony. “There is no reason,” he wrote, employing a lame bit of reverse logic, “for insisting now or ever that the ‘Blond Eskimos’ of Victoria Island are descended from the Scandinavian colonists of Greenland, but looking at it historically or geographically, there is no reason why they might not be.”

—TWO—

Stefansson’s new expedition, which again included Rudolph Anderson, was to search for new land in the Beaufort Sea, notably “Crocker Land,” which Robert Peary claimed to have seen in the misty distance during his quest for the Pole. It would be a three-winter, six-man expedition, and it would also attempt to measure the extent of the continental shelf in Arctic waters. For this Stefansson again secured the co-operation of the American Museum of Natural History but also that of the National Geographic Society, each of which was prepared to contribute $2,500 to the enterprise. Through his friendship with Professor James Mavor of the University of Toronto, another Arctic enthusiast, he also lobbied the prime minister, Robert Borden, for official support.

The whole question of Canadian sovereignty over the Arctic had become a major issue, and Borden was eager to ensure that any newly discovered lands would be Canadian. Stefansson, who knew exactly how to handle the prime minister, pointed out that as an American citizen and leader of the expedition, he would have to claim any new land for the United States—unless, of course, Canada became a partner in the venture. Borden turned the matter over to cabinet, whose members could not stomach any Yankee-led expedition claiming territory for the Land of the Free. They decided, in Stefansson’s words, “that it would be beneath Canada’s dignity to go into partnership with others in such an expedition.” Instead, the Canadian government would take over the entire venture, placing it under the Department of the Naval Service. With that the two American institutions bowed out, and the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913 was born.

Herein lay a recipe for trouble. When Stefansson reported his new deal to the National Geographic Society in February 1913, that organization made one condition: unless he got the Canadian expedition underway by June, the society would revert to its own investigation of Crocker Land. At the same time, the Canadian government decided it wanted to expand the venture beyond mere exploration. There would now be

two

parties, both acting for Canada and both under Stefansson’s leadership.

The Northern Party would follow an expanded version of the original plan. Its task would be “to discover new land, if any exists, in the million or so square miles of unknown area north of the continent of North America and west of the Parry Islands.” The vast frozen expanse of the Beaufort Sea stretched from the continental coastline north to the Pole. You could hide the province of Newfoundland in its waters and still have plenty of room left. Who was to say that another continent might not lie hidden under the ice? Peary had surely seen

something

when he glimpsed “Crocker Land” in the distance.

The Southern Party would be formed under Anderson, acting as Stefansson’s deputy, to engage in anthropological, archaeological, and zoological research on the Arctic coast. That would require fifteen trained scientists, most of whom had no Arctic experience, together with a support group to travel with them. Thus Stefansson’s tight little party of six was expanded to more than seventy, including Inuit.

That was a tall order, given the early deadline set by the National Geographic Society. It would have been sensible to forget about Crocker Land, which didn’t exist anyway, as later explorations would reveal. But Canadian nationalism together with Stefansson’s own impetuosity forced the issue. Now, on short notice, he had to comb North America and Europe for an appropriate scientific staff, complete some contracted articles for

Harper’s

magazine, take passage to England to enlist the aid of the Canadian High Commissioner, Donald A. Smith (Lord Strathcona, who gave him a personal cheque for a thousand dollars), and try to complete his book, an early chapter of which he managed to dictate during the Atlantic crossing.

Before Canada became involved, Stefansson had taken it upon himself to buy a ship to navigate the Beaufort Sea and the Arctic coast. He had several in mind but settled on a 247-ton brigantine, the

Karluk

, which had done duty as a whaler but was now laid up in San Francisco. Although it was not ideal for the purpose, the impulsive explorer insisted it was the only ship available, and besides, it was a bargain—a mere $10,000. He closed the deal with a down payment of $500, expecting that whatever sponsor took on the venture would underwrite the cost. The

Karluk

was sent to the government’s naval dockyard at Esquimalt, B.C., where it underwent repairs at a cost of $6,000, a hefty sum since it had already undergone repairs before being sold.

Bob Bartlett, the

Karluk

’s designated captain, a seasoned Arctic hand who had been with Peary in 1909, was more than dubious. The ship, in his opinion, was absolutely unsuitable for spending a winter in the ice. Should it take the expedition north, it would have to return south before the freeze-up; it didn’t have sufficient beams or sheathing to withstand the pressure of the ice pack.

Stefansson’s response was that the ship had wintered in the Arctic a dozen times and was as good as any whaler in the western Arctic. “Besides,” he said, “we have to use [the] only ship we have.” As usual, he was eager to get moving, and in this he was abetted by the government, which was as anxious as he was to get Canada’s name on any unknown islands in Arctic waters.

As an explorer, Stefansson preferred to plunge ahead, heedless of detailed planning, confident that everything would work out. His friend Richard Finnie described him as “really a lone wolf explorer … at best when travelling by himself or with a few congenial followers.” Later, at a ceremony in New York, Robert Peary would describe him as “the last of the old school” of Arctic explorers, “the worker with the dog and the sledge.” But now he was “leading an expedition that would eventually entail the use of half a dozen vessels.”

Stefansson dragging a seal across the ice, an image that was reproduced on the cover of

The Friendly Arctic,

perhaps his most controversial book

.

As a one-man operator Stefansson had always been an improviser, roaming the frozen wilderness, acting instinctively on his own, free of authority, always sure that something would turn up. Now he was in charge of a major enterprise that his sponsors had expected him to plan perfectly—but he had left too little time for organization. In fact, there was no organization. During the time the venture was being mounted in Victoria, B.C., he was absent because of his other commitments. There was no supervisor because he could not delegate, and he did not turn up to take charge until late in the enterprise.

There were further complications. Not only did the fifteen scientists lack Arctic experience but nobody, apparently, had figured out a system of packing and stowing the goods of the two parties. To carry the scientists and the extra equipment, two gasoline schooners had to be bought, the

Alaska

and the

Mary Sachs

, both with auxiliary engines. The supplies purchased for both parties were put aboard without any thought or planning. Boxes intended for the Northern Party were mixed up with others intended for the Southern. The

Karluk’s

decks were piled with fifty tons of bagged coal and sacks of fresh meat, vegetables, snowshoes and skis, canoes, alcohol, drums, and assorted wooden boxes. The same disorder existed below deck.

Kenneth Chipman, the expedition’s topographer, was angered and disillusioned by the disorganized arrangements. As he told his diary, “The responsibility for systemizing things has never been given to any one man.” Boxes repacked in Esquimalt, when the division between the two parties was made, were either poorly packed or even half empty. As Stefansson himself wrote, “we have had a good deal of trouble and difficulty in finding certain articles that got shoved underneath other cargo.”

By the time he reached Victoria, the full complement of the two parties and the ship’s crew had already been selected. It was not a happy group. William Laird McKinlay, a diminutive twenty-four-year-old meteorologist who had been hired by telegram for the Southern Party, was skeptical of the crew that had been picked up from Pacific Coast ports before Bob Bartlett took over the captaincy of the

Karluk

. McKinlay, who was to become a lifelong critic of Stefansson, thought they were good enough seamen but lacked “the other qualities which would be necessary for harmonious living in the kind of circumstances which might face us in the north.” One crew member, he noted, was a drug addict; another suffered from venereal disease; two more had managed to smuggle liquor aboard ship.

Most of the scientists, of course, had no idea what they were facing and were given no training in polar conditions before the ship left Victoria. Chipman tried to stir up enthusiasm for the venture among other members of the party but failed. There was “practically no confidence in the leader [Stefansson] and little assurance of getting good work done.”

Much of this pessimism sprang from the cumbersome mix of the two-party expedition insisted upon by the Canadian government. Stefansson was to report to the Naval Service; the scientists were to report to the Geological Survey, an arrangement marked by interservice rivalry. The scientific staff was alarmed to find that Stefansson would be in overall charge while Anderson of the Southern Party would be his deputy.

Stefansson had made it clear to the government that he didn’t want a salary of any kind. He would work for free because he expected to pay for his efforts by writing magazine articles and a book and by giving lectures about the Arctic. As an unpaid leader he would be, in his own mind at least, answerable to no one. He would make his own decisions as he always had, without bureaucratic interference, and he alone would profit financially from the expedition. He would retain exclusive publication rights in Canada, the United States, and Europe for a full year after the end of the adventure. In Victoria he directed that all expedition members must turn over all their personal diaries to the government office after the expedition ended. That did not sit well with the scientists, who insisted on confronting their leader. Several members of the Southern Party, including Anderson, tried to resign, but as Chipman recalled, “the thing had gone so far that we could simply make the best of it.” Stefansson calmed down, giving Anderson the rights to reports on the activities of the Southern Party for two New York newspapers with which he, Stefansson, had a contract, but no others.

The problems did not go away. The scientists had little faith in Stefansson’s personal ambitions. His determination to live by his wits and push aside all obstacles clashed with the cautious, conservative attitude of the Southern Party members, whom he tended to patronize, as his published reference to the poor physical condition of one of them suggests. “Such softness,” he wrote, “is the inevitable result of the time-honoured polar explorer custom of spending the winter in camp.… Such idleness makes muscles flabby and (what is worse) breeds discontent, personal animosities, and bickering.…”

The discontent continued after the

Karluk

reached Nome. Stefansson, who was used to a lean, mean operation, was dealing with a group of scientific experts, many of whom had not comprehended that life in the Arctic differed from a cozy existence in Ottawa. He grew irascible at the questions flung at him about the expedition’s plans. When somebody wanted to know if the twenty tons of provisions purchased in Seattle would be suitable for sledge travel, he declared that the questioner had no right to ask. When James Murray, the oceanographer, acting as a spokesman for the party, asked what arrangements had been made for fur clothing, Stefansson retorted that the question was impertinent. Murray feared that the

Karluk

might get crushed in the ice and tried to suggest that the Northern Party establish a base on shore as well as on the ship. But Stefansson insisted on dealing with all the problems in his own way. When he bluntly told the scientific members that lives were secondary to the success of the expedition, they were shocked at what to them was inexcusable callousness. Irritated by their flood of queries, Stefansson told them that he was in command of the expedition and they must have confidence in him. According to Chipman, he made the remarkable statement that the expedition was not essentially scientific, and that scientists were inclined to be narrow-minded and engrossed in their own lives.