Practically Perfect (18 page)

Read Practically Perfect Online

Authors: Dale Brawn

On the occasions when someone in town spoke of Gauthier, it was likely to relate a story about his drinking. The mayor, for instance, recalled the time he dropped by Gauthier’s house. As he walked up to the door, a bullet whizzed by his head. Gauthier quickly admitted to the shooting, but said he was not really trying to hit the mayor, just scare him a bit. The two men had a long relationship, albeit not a particularly pleasant one. The mayor frequently received complaints about Gauthier’s rowdiness, and once, when things had gone too far, he ordered local hotels to stop serving the garage-man. But that did not stop Gauthier from drinking and acting rowdy. Typical was an anecdote told by the town secretary, who remembered Gauthier breaking three window panes trying to get into his house one morning at 3:00 a.m. Gauthier said he wanted to pay his property taxes.

If Gauthier’s widow had been better able to cope with her husband’s death, things would almost certainly not have ended as they did. Although Alice married Ulric in 1937, she was never really committed to making the marriage work. After Alice hanged herself, the police reopened their investigation into the death of Ulric, and most of the people they interviewed were asked the same question: “Did you ever hear that Gauthier’s wife ran around with other men?” Almost everyone agreed that he had. The exception was the local veterinarian, who, when asked the question, replied, “No, I never heard she ran around with other men.”

[1]

Well, then what did you hear? “I heard only that she had relations with other men.” According to most of those who testified, Roland Asselin was one of those with whom she was most intimate.

These rumours could not be ignored, and for the next ten months Quebec Provincial Police officers looked for some concrete evidence that Asselin, or Asselin and Alice, murdered Ulric Gauthier. Persistence paid off. On December 29, 1947, a little over a year after Gauthier was killed, Asselin confessed, not to murdering the husband of his lover, but to accidently shooting him. According to Asselin, the two men drank beer at several bars just outside St. Telesphore. As they left the last one they got into a heated discussion over Gauthier’s insistence that he drive Asselin’s cab. The two argued, and Gauthier produced a revolver. They fought, and during the scuffle Asselin wrestled the gun away from Gauthier. He fired a single shot, to scare him, but the bullet struck Gauthier in the side of the head.

After Asselin gave his statement to the police he was taken into custody. A third coroner’s inquest was quickly convened to look into the death of Ulric Gauthier. The hearing lasted just two hours, and it took juror’s only fifteen minutes to find Asselin criminally responsible for Gauthier’s death. A week later the cabbie was arraigned on a charge of murder. His trial got underway during the second week of June 1948, and after six days of testimony he was found guilty. The only real question was whether Gauthier’s death was the result of manslaughter or murder. The presiding judge had little doubt about which it was, and shared his conviction with jurors. He told them that they should not believe that Gauthier was shot with his own gun, since it was unthinkable that someone as demonstrative as the dead man could possess a revolver and not wave it around in front of others. On the other hand, they could accept as fact that Asselin had a gun on the evening in question.

Jurors reached a verdict in a little over an hour. Once they made their decision known, court was adjourned for a few minutes to allow the presiding justice to prepare his sentencing remarks. Only one sentence was available to him. Although Asselin showed little emotion throughout his trial, as soon as he was returned to his cell to await the return of the judge, he collapsed. His guards quickly laid him on a bench, and summoned a doctor. After a lengthy delay, Mr. Justice Wilfrid Lazure formally postponed sentencing until the following morning, when Asselin was informed he was to hang on October 1. But he was not executed then, nor on January 14, 1949, March 25, or March 31. Asselin’s luck ran out when the Quebec Court of Appeal ruled there would be no more reprieves; the condemned man was to be executed on June 10. Just after midnight Asselin was hanged, and one half hour later he was declared dead.

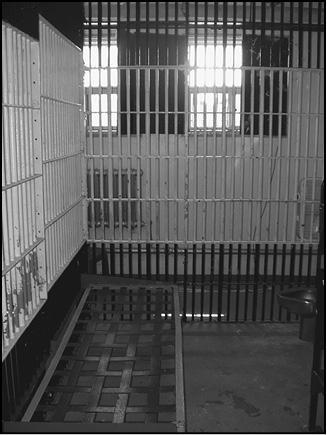

The deaths cells where condemned prisoners were held were small, utilitarian, and totally lacking in privacy. Twenty-four hours a day a member of the death watch sat outside the cell, keeping a written record of everything the prisoner said or did. The windows shown in this photo were covered when a death cell was occupied so that a prisoner would not know how quickly, or slowly, time passed.

The deaths cells where condemned prisoners were held were small, utilitarian, and totally lacking in privacy. Twenty-four hours a day a member of the death watch sat outside the cell, keeping a written record of everything the prisoner said or did. The windows shown in this photo were covered when a death cell was occupied so that a prisoner would not know how quickly, or slowly, time passed.

Author’s photo.

Roland Genest:

He Never Murdered a Woman He Didn’t Love

They made quite a pair. Both were young, vivacious, and seemed to get fulfillment out a relationship that seemed equal parts love and violence. She was only twenty-one when she met the good looking twenty-five-year-old. By the time she realized he was married, the woman was deeply in love. So much so that when he suggested she kill his wife, she did not hesitate. For almost two years the pair got away with murder, and then he tired of her constant nagging. That’s when it all came to an end.

Rita Genest was the first to die. She was just twenty-three, but in the opinion of her husband, she was no fun. A few months before Rita was beaten to death Roland Genest was on his own when he noticed a young woman riding by on a bicycle. They began to talk, and before long were dating. She was already in love when Genest told her that they would have to stop seeing each other — he was a married man. At his trial Genest said he forgot who brought up the subject, but he distinctly remembered that his lover volunteered to murder Rita. That way, she said, Roland would have an alibi, and he would be single again. In a matter of a few hours they decided to do it. Genest bought an iron bar, gave his co-conspirator a key to his apartment, and told her to set fire to the room when Rita was dead; which is exactly what she did.

Rita Genest was murdered on May 21, 1951. The evening she died Rita and her husband went out to supper with her brother. After dropping her off at home, the men spent the rest of the evening drinking and gambling. About 11:00 p.m. neighbours noticed smoke coming from the Genest apartment and called the fire department. By the time fire fighters arrived, the bedroom was completely gutted. All that remained was a smouldering mattress and blood. Lots of it. Firefighters promptly called the police. About an hour after they arrived, Roland Genest drove up. When he was taken to police headquarters twenty minutes later his alibi paid off in spades. He was released after providing investigators with a satisfactory account of his whereabouts when the fire started.

A coroner’s inquest was held on May 30, but soon adjourned to give investigators more time to gather evidence. Before it adjourned, however, jurors heard from the two provincial medico-legal experts assigned to the Genest case. They testified that Rita died from two skull fractures, inflicted by a blunt instrument with a narrow edge, and that she was dead when her bedroom was set on fire. Their conclusion was based on both the extent of her head injuries, and the fact there was no trace of carbon dioxide in her blood. The last anyone heard about the investigation was a brief report published a few days after the murder. According to the newspaper article, Montreal homicide detectives had absolutely no clue who murdered Rita. For the next twenty-one months her file lay untouched.

That changed on February 19, 1953, when the nude body of a woman was discovered lying in a farmer’s field on Île Bizard, a small island now a suburb of greater Montreal. The woman was found about one hundred feet from a much travelled road, and had been badly beaten about the head. She had also been stabbed numerous times. A near total absence of blood at the scene suggested to investigators that the victim was murdered elsewhere, and her body transported to the field. As one detective noted, “There was hardly any blood around the body, which leads us to believe she was carried there in a blanket after being knifed and hammered to death.”

[2]

Although the body of the woman lay in their morgue, the police had no clue who she was. They ran her fingerprints through their own database and that of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, but the searches produced no leads. They decided to publish a photo of the woman’s face in local newspapers and invite Montrealers to visit the city morgue. Their appeal attracted an assortment of the morbidly curious, and those desperate to know whether the corpse was that of a missing loved one. For two days and nights hundreds of men, and a few women, slowly walked by the gurney on which the body lay. The detective leading the investigation made no apologies for what his team of investigators did. “Some of these people were just curious” he said. “But they claimed the victim’s description fitted that of someone they knew. We can’t take chances, because our only chance of learning who the woman is lies with somebody that knew her.”

[3]

Ultimately, that somebody was her mother. Two hours after she and two sisters of the victim identified the missing woman as Marie Paule Langlais, the police took Roland Genest into custody as a material witness. Forty-eight hours later he confessed to the murder, although there is considerable doubt he did so voluntarily.

According to Genest, after the police picked him up on a Montreal street they took him to a police station, where he was put in a cell. The next morning officers read him his rights, and began questioning him about what he knew of the murder of Langlais. All he admitted was that he saw her the day before her body was found, and that the two had a disagreement. Langlais accused him of flirting with another woman. And that was that, at least according to the detectives who interviewed Genest. They said that when they returned to his cell the following day, they again read him his rights, but this time he wanted to get something off his chest, and he began talking. By the time they were done Genest confessed not only to killing Langlais, but to taking part in the murder of his wife as well. At least that was the official version of events. Genest saw it differently.

He said after he was picked up one of the investigating officers came into his cell alone. The detective took off his rings and watch, rolled up his sleeves, and began hitting him. For fifteen minutes the officer punched him in the face and body, and he smashed Genest’s head on a table. By the time the policeman tired, Genest said he was ready to confess. The detective then stopped hitting him, took out a statement already written on a piece of paper, and had Genest sign it.

At his trial the lawyer prosecuting the case could not see what the problem was. He asked the accused killer if he had indeed “told the police you hit Marie Paule over the head with a baseball bat? Do you admit that this is true.” Genest said yes, he said that. “Do you admit that you told them you hid the body on Île Bizard. Do you admit this is true?” Again the answer was yes. “Do you admit you told them where her clothes were? Do you admit this is true?” Another yes. Then Justice Wilfrid Lazure (the same judge who sentenced Roland Asselin to death) interrupted. Lazure wanted to know why Genest would tell the police these things if they were not true. Because, the accused said, he was told the beating was going to continue until he confessed. He did not even read the statement he signed.

[4]

Before his murder trial got underway, however, the inquest adjourned after the body of Langlais was discovered was reconvened. Sitting in the crowded coroner’s court were the mother, five sisters, and four brothers of the dead woman. The statement Genest made to the police was not admitted into evidence, but the court heard testimony from a number of the officers who investigated the murder. They said as a result of information given them by Genest, they recovered several items connected with the killing, including the partially burned clothes of the dead woman, found just outside a Montreal area village, a bloodstained knife recovered from the third story roof of an east end apartment building, and engagement and wedding rings were found in a private residence. Also recovered was the baseball bat used to beat Marie, and the bloodstained tarpaulin on which Genest placed Langlais when he transported her body to the spot where it was discovered.

After hearing the evidence the coroner’s jury deliberated six minutes before finding Genest criminally responsible for causing the death of Marie Paule Langlais. Moments later the short, dapper accused killer was formally charged with murdering his girlfriend. Everything that followed the confession was a mere formality, and when Genest’s trial got underway on May 19, 1953, his guilt was never in question. The only issue was whether he should be convicted of murder or the lesser charge of manslaughter. The first offence involves an element of premeditation and planning, while the second consists of a killing carried out in the heat of passion.

Genest was the first witness to testify. He said he picked up his girlfriend when she got off work at the Saint-Jean-de-Dieu hospital, and the two drove to a garage he rented, where they washed his car. They began to argue over medicine he kept in a trunk.