Poisoned Bride and Other Judge Dee Mysteries (24 page)

Read Poisoned Bride and Other Judge Dee Mysteries Online

Authors: Robert H. van Gulik

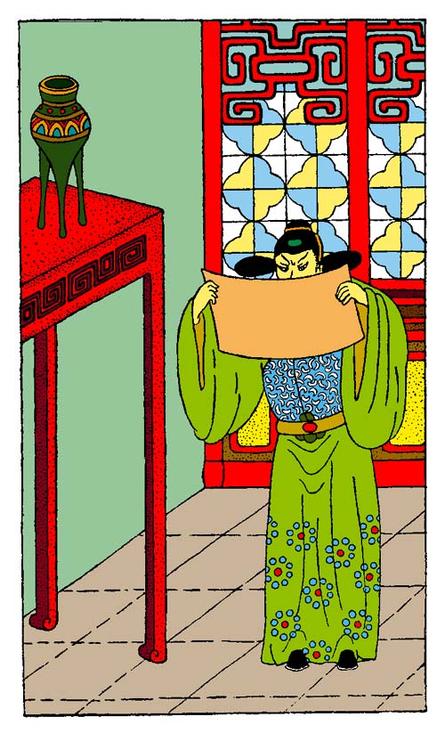

Judge Dee took the scroll, and slowly unrolled it, holding it high in both hands, so that the Imperial seal never was below his head. Judge Dee read aloud in a reverent voice:

Whereas, respectfully following the Illustrious Example of Our August Ancestors, it is Our traditional policy to appoint meretorious officials to those functions where their talents find widest employment, thus enabling them to exhaust their loyalty to Us on high, and to protect and foster Our people below;

It had been originally Our pleasure to promote the said Dee to the office of prefect of Hsu-djow.

Of late, however, pressing affairs of State leaving Us no rest either day or night, it is Our will that all those of extraordinary talents in Our Empire shall be near Us, so that We may summon them to assist the Throne whenever We so desire;

We now, therefore, on this second day of the fifth moon of the third year of Our Reign, issue this Edict, whereby the said Dee is appointed President of Our Metropolitan Court of Justice. Tremble and obey!

Drawn up by the Grand Secretary of State

So be it. Despatch by courier.

Judge Dee slowly rolled up the Edict and replaced it on the table. Then, turning in the direction of the capital, he again prostrated himself, and knocked his head on the floor nine times in succession to express his gratitude for this Imperial favour. Having risen, he called Ma Joong and Chiao Tai and ordered them to stand guard in front of the court hall. Nobody was to be allowed inside as long as the Imperial Edict remained there.

A servant came in and reported that the horses of the messenger’s escort had been changed and that everything was ready for his departure. The messenger said that he regretted leaving so soon, but he still had urgent business in the neighbouring district. So Judge Dee conducted him to the hall, where the Imperial Edict was handed back to him with due ceremony. Then the messenger hurriedly took his leave.

Judge Dee waited in his private office, while the entire personnel of his tribunal assembled in the court hall.

As Judge Dee ascended the dais, the crowd of constables, guards, scribes, clerks and runners all knelt down to congratulate the judge, and this time his four faithful lieutenants also knelt down in front of the dais.Judge Dee bade them all rise, and then said a few appropriate words, thanking them for their service during his term of office. He added that the next morning all would receive a special bonus, in accordance with their rank and position. Then he returned to his private office.

He finished his report on the execution of the criminals, and then had the chief steward called in. He ordered him to have everything prepared in the reception hall early the next morning for the entertainment of the local gentry and the lower functionaries of the district administration, who would assemble there to offer their congratulations. He was also to have a separate courtyard in the compound cleared as temporary quarters for the new magistrate and his retinue. These matters having been settled, he told the servants to bring his dinner to his office.

There was rejoicing all over the tribunal. Sergeant Hoong, Ma Joong, Chiao Tai and Tao Gan talked excitedly about life in the capital and then got busy planning a real feast for that night in the best inn of the city. The constables were happily arguing about the exact amount of the bonus they would receive the next day.

Everyone in the tribunal was happy and excited. But in the street ,there were heard the wails of the common people assembling in front of the tribunal, bemoaning the fate that took this wise and just magistrate away from them.

Judge Dee, seated behind his desk in his private office, started to put the files in order for his successor.

Looking at the pile of leather document boxes that the senior scribe had brought in from the archives, he ordered the servants to bring new candles. For he knew that this would be another late night.

THE END

Wu-tsê-t'ien-szû-ta-ch'i-an

[Note 1]

), “Four great strange cases of Empress Wu’s reign.”

The printed editions (b) and (c) are practically identical. The text of (a), however, is much more compact: it lacks many irrelevant passages contained in (b) and (c), and the contents of some chapters are rearranged in a more logical way. This manuscript is written in indifferent calligraphy, with many unauthorised abbreviated characters. Yet it is singularly free from real mistakes: wrong characters in the names of several historical persons occurring in (b) and (c), are here given in their correct form. It would seem that this novel — as most literary productions of this type — circulated for many years in manuscript form only, and that (a) was edited by a scholar, while (b) and (c) are based upon inferior manuscript copies. I have, therefore, taken (a) as the basic text for my translation.

This book numbers 64 chapters, ch. I-XXX (which hereafter are briefly referred to as Part I) are devoted to the earlier part of Ti Jên-chieh’s career, and more especially to three criminal cases solved by him; ch. XXXI-LXIV (hereafter called Part II) describe his career at the Imperial Court. In all texts, these two parts differ widely in style and contents. Part I is written in a fairly compact style, and cleverly composed. The style of Part II, on the contrary, is prolix and repetitious, while the plot is clumsy, and the characters of the new persons introduced are badly drawn. Further, while Part I is written with considerable restraint, in Part II there occur various passages which are plain pornography, e.g. where the relations of Empress Wu with the priest Huai-i are described.

If one reads the author’s own introductory remarks in Chapter I carefully, it will be found that his summary of the contents of this book recapitulates in a few terse sentences the main happenings described in Part I. The phrase “People who commit murder to be able to live to the end of their days in an odour of sanctity” refers to the young lady in the

Case of the Strange Corpse

; “people who commit crimes in order to amass riches” refers to the murders of Shao Li-huai; “people who get involved in crimes through adulterous relationships” refers to Hsü Tê-tai; the phrase “people who meet sudden death by drinking poison not destined for them” refers to

The Case of the Poisoned Bride

; and, finally, the phrase “people who through words spoken in jest lay themselves open to grave suspicion” refers to Hu Tso-pin, in the same criminal case. While thus the contents of Part I are indicated in detail, all the thirty four chapters of Part II are summed up in but one brief phrase, saying “People who defile the Vernal Palace”.

Now in my opinion this last sentence is an interpolation, and the entire Part II a later addition, written by some other author. On the basis of the data available to me at present, I am convinced that Part I was an original novel in itself, entitled

Ti-kung-an

, “Criminal Cases solved by Judge Ti.” This novel ended in a way which is very typical for Chinese novels, viz. with Yen Li-pên recommending Judge Ti to the Throne for promotion; most Chinese novels dealing with official life end in a veritable orgy of promotions. In my opinion a later scribe of feeble talents added the 34 chapters of Part II, and changed the title, in order to make the book seem more attractive to the general public. For Empress Wu being notorious for her extravagant love-affairs, her name in the title would suggest a book of pornographic character

[Note 2]

). Further, the title

"Four great strange cases of Empress Wu’s reign

” is inapposite, inasmuch as Part II does not describe a “case” at all, but simply is a garbled version of some historical happenings.

The present translation, therefore, covers only Part I, which I consider genuine, and which makes a good story in itself.The hero of this novel is the famous T'ang statesman Ti Jên-chieh (630-700); his biography is to be found in ch. 89 of the

Chiu-t'ang-shu

, and ch. 115 of the

Hsin-t'ang-shu

. It would be interesting to try to verify in how far the criminal cases related in this novel have any real connection with Ti Jên-chieh. His official biographies mentioned above merely state that as a magistrate he solved a great number of puzzling cases, and freed many innocent people who had been thrown into prison because of false accusations; neither these official biographies, nor local histories and other minor sources which I consulted give any details about these cases solved by Judge Ti. In order to answer this question one would have to make a comparative study of all the famous older detective stories. Here it may suffice to add that for instance the plot of the

Poisoned Bride

and of the

Strange Corpse

are used also in other old Chinese detective novels; cf. below, the notes to chapter XXVIII-XXIX.

Ti Jên-chieh’s nine memorials to the Throne are to be found in the

Shih-li-chü-huang-shih-ts'ung-shu

, a collection of reprints collated by the famous Ch'ing scholar Huang P'ei-lieh (1763-1825), under the title

Liang-kung-chiu-chien

.

“While being strict, yet shun the doctrines of Shên and Han.”