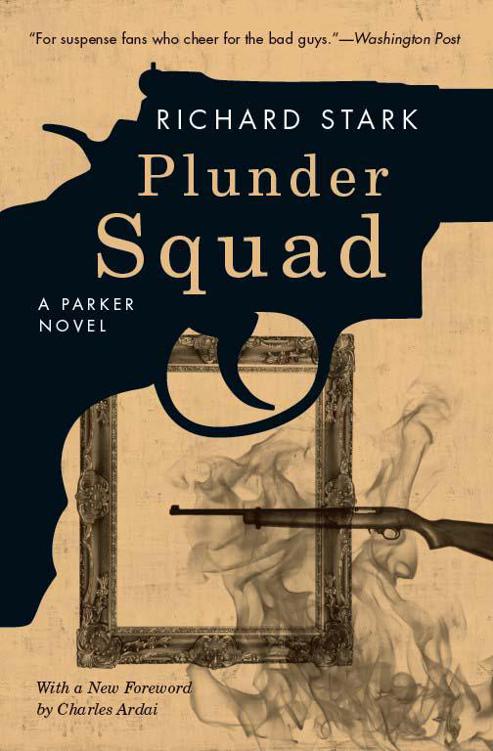

Plunder Squad

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 60637

Copyright © 1972 by Richard Stark

Foreword © 2010 by Charles Ardai

All rights reserved

University of Chicago Press edition 2010

Printed in the United States of America

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-77093-2 (paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-77093-1 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-77291-2 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stark, Richard, 1933-2008.

Plunder squad : a Parker novel / Richard Stark; with a new foreword by

Charles Ardai.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-77093-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-77093-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Parker (Fictitious character) I. Title.

PS3573.E9P59 2010

813’.54—dc22

2010007749

Information about the complete list of Richard Stark books published by the University of Chicago Press—and electronic editions of them—can be found on our website:

http://www.press.uchicago.edu

A Parker Novel

by

RICHARD STARK

With a New Foreword by Charles Ardai

The University of Chicago Press

Praise for Richard Stark and the Parker novels:

“Richard Stark’s Parker . . . is refreshingly amoral, a thief who always gets away with the swag.”

—Stephen King,

Entertainment Weekly

“Stark was, and is, a pseudonym for Donald Westlake, a writer so inventive and wildly fecund that he had no option but to publish under other names. . . . It’s excellent to have [his novels] readily available again—not so much masterpieces of genre, just masterpieces, period.”

—Richard Rayner,

L. A. Times

“If you’re looking for crime novels with a lot of punch, try the very, very tough novels featuring Parker by Donald E. Westlake (writing as Richard Stark).

The Hunter, The Outfit,

The Mourner,

and

The Man with the Getaway Face

are all beautifully paced [and] tautly composed.”

—James Kaufmann,

The Christian Science Monitor

“Parker is a brilliant invention. . . . What chiefly distinguishes Westlake, under whatever name, is his passion for process and mechanics. . . . Parker appears to have eliminated everything from his program but machine logic, but this is merely protective coloration. He is a romantic vestige, a free-market anarchist whose independent status is becoming a thing of the past.”

—Luc Sante,

The New York Review of Books

“Richard Stark is the Prince of Noir.”

—Martin Cruz-Smith

“One of the most original characters in mystery fiction has returned without a loss of step, savvy, sheer bravado, street smarts, or sense of survival.”

—

Mystery News

“The Parker novels . . . are among the greatest hard-boiled writing of all time.”

—

Financial Times

(London)

“Richard Stark (which must be the pseudonym of some long-experienced pro) writes a harsh and frightening story of criminal warfare and vengeance in

The Hunter

with economy, understatement and a deadly amoral objectivity— a remarkable addition to the list of the shockers that the French call

romans noirs.

”

—Anthony Boucher,

New York Times Book Review

(1963)

“No one can turn a phrase like Westlake.”

—

Detroit News and Free Press

“Westlake’s ability to construct an action story filled with unforeseen twists and quadruple-crosses is unparalleled.”

—

San Francisco Chronicle

Parker Novels by Richard Stark

The Hunter (Payback)

The Man with the Getaway Face

The Outfit

The Mourner

The Score

The Jugger

The Seventh

The Handle

The Rare Coin Score

The Green Eagle Score

The Black Ice Score

The Sour Lemon Score

Deadly Edge

Slayground

Plunder Squad

Butcher’s Moon

Comeback

Backflash

Flashfire

Firebreak

Breakout

Nobody Runs Forever

Ask the Parrot

Dirty Money

This is for

Justin and Debby,

who’ve been needing a book

By the time Donald Westlake, the prolific soul behind the “Richard Stark” pseudonym, sat down to write

Deadly Edge, Slayground

, and

Plunder Squad

, he’d already written a dozen books about the professional thief Parker and his too-often ill-fated attempts to separate institutions and individuals from their valuables. After dreaming up a dozen exploits in nine years for the same protagonist, the author could have been forgiven if he’d begun to repeat himself or if the series had started to run out of steam—but what happened was precisely the opposite.

Following a quartet of novels whose thematic unity is suggested by their similar titles—

The Rare Coin Score, The Green Eagle Score, The Black Ice Score, The Sour Lemon Score

—and which began to soften the edges of the Parker character (principally by adding a love interest), Westlake decided to take Parker into harder, darker territory. The result was as bracing as a slap across the cheeks.

Penned over the course of just two years (a period during which Westlake wrote at least three other novels as well),

Deadly Edge, Slayground

, and

Plunder Squad

reinvigorated the Parker character, confronted him with some of his most memorable crises,

and went a long way toward establishing the Parker series as a landmark of crime fiction. When you ask people who revere the Parker books which ones they admire most, they’re likely to name one of these three, or else the epic sequel to

Slayground, Butcher’s Moon

. After

Butcher’s Moon

, Parker wasn’t heard from for twenty-three years—it was as if the character had finally burned himself out with the sheer intensity of these last four grueling jobs. But what a way to go.

Reading the Parker novels—especially if you are fortunate enough to read several back-to-back—is a little like watching a jazz musician at work. The performance begins with a familiar melody, the unadorned restatement of a basic theme; but then the performer cuts loose, interpreting, elaborating, inverting, transforming, improvising. Donald Westlake had an almost frightening ability to sit down at the keyboard and just let his fingers go, extemporaneously unfolding his stories seemingly in real time with breathtaking invention.

At a certain level of abstraction, of course, the Parker novels are all the same: there’s the planning of the job, the assembling of the crew, the execution of the heist, the escape with the loot, the betrayals and double crosses, the tracking down of missing money, the remorseless elimination of men who pose a threat, the drive for survival at all costs. And yet, Westlake somehow manages each time to assemble these elements into a thoroughly new book. Bix Beiderbecke famously said he never played a solo the same way twice, and neither did Westlake. It may be the same song each time, but all the notes are different.

Consider:

Deadly Edge

opens with Parker and crew robbing

a rock concert of its cash take,

Slayground

with Parker and crew robbing an armored car.

Plunder Squad

’s opening scenes describe two heists being planned: one an attempt to rob a department store of its cash take and one to rob an armored car. A trained eye might be able to detect some similarities here. But all it takes is reading a few chapters into each to discover just how different these books are from one another.

Deadly Edge

turns out to be the story not of the heist, but of a pair of psychopaths who begin killing off the members of the heist crew one by one.

Slayground

becomes a claustrophobic tale of survival when Parker gets trapped in a shuttered amusement park with a team of gangsters hunting for him. And

Plunder Squad

unfolds into a melancholy, almost autumnal reflection on the burdens of Parker’s chosen profession, as one job after another disintegrates before his eyes, and a rare moment of mercy he showed in a previous book comes back to haunt him. It would be hard to imagine three more different books.

In fact, these rather similar starting points actually generated four different books, since Westlake took the opening scene of

Slayground

almost verbatim from a book he’d written two years prior (also under the Stark pseudonym), The

Blackbird

. After completing the armored car robbery, Parker and his sometime partner in crime Alan Grofield wind up in a car crash as they attempt to escape. Parker gets away on foot while Grofield is captured by the authorities. In

The Blackbird

, we follow what happens next to Grofield as he’s taken to a hospital and coerced into a mission for a secret government agency; in

Slayground

, we instead follow Parker as he desperately hides out in that deserted amusement park and undergoes a one-man-against-twenty ordeal that makes the movie

Die Hard

look like, well, a walk in the park. Westlake’s deriving two completely different novels from the same opening scene is a bit of virtuoso finger work that demonstrates the author’s

playfulness, as well as his interest in formal experiments. (Another example: in

Plunder Squad

, Westlake has a scene in which Parker meets detective Dan Kearny, a character created by fellow mystery writer Joe Gores; Gores included the same scene, told in reverse from Kearny’s perspective, in his novel

Dead Skip

the same year.)

Part of the pleasure in cracking open a Parker novel is that you never know just what you’re going to get. You know you’re in the hands of a master storyteller and in the company of a fascinating character—but that’s all you know and all you can count on. In a genre too often known for predictability, it’s exhilarating not to be able to guess what’s going to be on the next page until you turn it and see.

Yet amidst all these twists and variations and surprises and reversals, one thing remains constant: Parker. He is unchanging, stable and steady and calm, unflinching and unfailingly professional. He doesn’t say much—Parker is more a doer than a talker (although when he does talk he is persuasive)—and doesn’t spend a lot of time on contemplation or introspection. He is a man of action in the most literal sense, and he acts decisively, relentlessly, and ruthlessly in pursuit of his goals.

In some ways, Parker is the embodiment of the Protestant work ethic, the consummate hard-toiling craftsman whose craft just happens to be robbery. He is intensely practical and self-reliant. (From

Slayground

: “He’d walked into this himself, it was up to him to walk back out again himself. He understood that, and he didn’t worry about it.”) He despises “wasted movement.” It “bother[s] him . . . to do illogical things”; he is “troubled . . . that all [is] not rationality.” He has no patience for the frivolity and functionlessness of pop music and modern art and, though the man likes a certain amount of sex in its proper place, he disdains sexual excess. He is careful, calculating; he has a purpose for everything

he does; he doesn’t indulge himself or others, or respect those who do. He is not, as far as we can tell, a happy man. He’s the best at what he does—but one wonders, does it give him any pleasure?

This question would baffle Parker. Parker doesn’t do things for pleasure—he does them because they’re his job, because they’re what he has to do. It’s true that some of the elements of domesticity that began to humanize the character in the preceding four books ripen somewhat in these three. Like any traveling salesman or long-haul trucker or touring-company actor, Parker has a home that he leaves for long stretches at a time but then returns to, to recharge. And he has a partner who waits for him there, eager to help him release his stress. (

Slayground

again: “Lately, a thaw had taken place. He liked knowing this house was here, in an isolated corner of New Jersey, with Claire waiting in it for him. . . . He enjoyed it.”) But the enjoyment he permits himself is of the narrowest sort: he likes Claire, but he makes it clear he doesn’t

need

her. Even when they’re together, Parker’s actions seem to spring not from desire but merely a will to accomplish his ends. Claire thinks of him as “unfeeling,” noting in

Deadly Edge

that “even when he was with her, he was in some manner away from her; he was the most locked-in man she’d ever met”; when she tells him, “You can relax here,” his internal response—unspoken, of course—is, “There was no answer to that. He was on guard everywhere.” And as it turns out, rightly so: within 100 pages of this silent comment, their sanctuary-like home will be invaded by one of the series’ most frightening villains, with bloody consequences.

Parker occupies a world of constant threat, where style counts for nothing. (

Deadly Edge

: “That was the edge Parker had; he knew that survival was more important than heroics. It isn’t how you play the game, it’s whether you win or lose.”) If he is constantly on guard, it’s because he has to be. He’s chosen a dangerous

life, and only someone with his capacity for turning off emotion, thinking clearly and quickly, and getting the job done—whatever job it is—could possibly survive the gauntlet Westlake makes him run.

Perhaps this is why the Parker series continued for so long and commanded such passion from readers; perhaps it’s why, even after twenty-three years of silence, Westlake ultimately found it irresistible to return to Parker and bring him back for another eight novels (and surely would have written still more if not for his untimely death on New Year’s Eve, 2008). Parker is tough enough and smart enough and good enough to handle anything that’s thrown at him, even by someone as ingenious as Donald Westlake. In Parker, Westlake met his match—and the clash of wills between the two, with its suggestion of irresistible force versus immovable object (

Could Donald Westlake invent a situation so dire that even he couldn’t get Parker out of it?

), makes for a set of stories that leave us still whipping through the pages breathlessly today, four decades after the white-hot blaze of their composition.

CHARLES ARDAI