Please Ignore Vera Dietz (21 page)

DRIVE CAR, DELIVER PIZZA—TUESDAY—FOUR TO EIGHT

I walk out the back door and stand in the fading, dusky sunlight. Larry joins me and lights a cigarette. The Charlies can’t get ahold of me here like they can when I’m in a small space. I don’t want any more drama. I just want to finish my shift, get home, and read the rest of Charlie’s note.

The dinner rush begins. Larry takes the town runs. Charlie stays with me all night as I deliver to the nice parts of town. He continues to try and steer the car to Overlook Road, but I keep telling him that I get off work at eight and that he’ll have to wait. In protest, he makes me endure an AC/DC song on his favorite heavy-metal station.

It slows down, like only a Tuesday can, and Larry and I are standing around in the back, talking and folding boxes. He tells me that he used to be a computer programmer, but hated it. So he’s working here and taking a few courses at the community college while he figures out what to do with his life. He wants to make movies. Says he’s written a bunch of scripts. I don’t tell him anything personal except that I’m a senior, and that I think he’s smart for going to community college.

He folds boxes tonight as if he’s been doing it for years.

“What classes are you taking?” I ask.

“The easy ones, for now. Catching up on math. Comp. What about you? You have a favorite class in school?”

I nod and reach for another box. “I love Vocab. It’s like spelunking in a cave you’ve been in your whole life and discovering a thousand new tunnels.”

When I stand up, Larry’s next to me, whispering Charlie’s voice into my ear. “Being dead is like that, too.” Then he adds, “Don’t open the envelope. You don’t want to see what’s inside.”

When I turn away from Larry and look toward the front of the store, the room is jam-packed with Charlies again. Fat ones. Skinny ones. Tall, short. Over by the bathroom, there’s even a black Charlie with an Afro and a 1970s pick stuck in it. There is a Charlie with a gray parrot on his shoulder, and a Charlie in a sad-clown costume, juggling limp puppies. I want to scream at him, “Jesus, Charlie! Will you just wait until I’m done with what I’m doing?” And as frustrated and freaked out as I am, I’m laughing a little. I’m laughing because Charlie is as hysterically impatient in death as he was in real life. I must be truly ready if I’m laughing at this.

Larry folds boxes next to the back door with an unlit Marlboro Red hanging out of his mouth, oblivious to the room full of Charlie molecules. I hear Marie up front, slapping fresh hot pies into boxes and slicing them, and I claim the order, even though it’s not my turn.

I know the road and vaguely know the address, so I grab four Cokes from the cooler and get into my car before anyone notices I’ve taken the wrong run. In the car, I hear the voices of a thousand Charlies, all of them at once. So I say, “Shut up, Charlie! Go away!” but they will not quiet. I think about what my father would do. The Zen master. Mr. Cool. He would relax his muscles. He would concentrate on his diaphragm, breathing. He would transcend. Breathe in. Breathe out. We have a wooden sign in the downstairs powder room that says:

CHOP WOOD, CARRY WATER

.

I think Zen-like, and whisper, “Drive car, deliver pizza.”

My delivery is in a Hispanic neighborhood. I pop in Santana to block out the loud whispers of Charlie. It’s a warm night, so the old Caribbean men are sitting on the sidewalks in dinner chairs, breathing. They don’t make eye contact. When I get back to the store, I sit there for a second and search for Charlie molecules, but he is gone. Marie is already cashing me out. I go into the bathroom to change, and have a quick look at myself in the mirror. There are no ghosts crowded in here with me, making me scribble things on toilet paper and eat them or trying to steal the air out of my lungs. I breathe on the mirror and fog it up, which proves I am alive—which, in turn, reminds me how lucky I am to be alive.

As I load my shirt into the washer for the night, I daydream about making a sign and hanging it around my neck. I could wear it to school tomorrow. It could read,

I MISS CHARLIE KAHN

.

As I drive home, I picture other signs—one for everyone who has a secret. Bill Corso’s would say,

I CAN’T READ, BUT I CAN THROW A FOOTBALL

. Mr. Shunk’s would read,

I WISH I COULD TOSS YOU ALL ON AN ISLAND BY YOURSELVES

. Dad’s would read,

I HATE MYSELF FOR NO GOOD REASON

.

My idea grows.

I imagine signs on every house on Overlook Road. I pass Tim Miller’s house at the bottom.

PROUD HATERS

. Up the hill past Charlie’s.

WIFE BEATER

. Past the Ungers’ house.

WE BUY SHIT TO MAKE OURSELVES BIGGER THAN YOU

. And up to the pagoda, where I’d stick the biggest sign of all.

USELESS BEACON OF DELUSIONAL OPTIMISM AND FOLLY

.

I park in the lot next to the glowing red beacon and look out over the city, and I feel like I belong here, even though I hate it here. We are one, the pagoda and me. Because when I think about it, I was also built from delusional optimism and folly.

A BRIEF WORD FROM THE PAGODA

Hey—the whole freaking world was built from delusional optimism and folly. What makes you so special? We’re all just making it up as we go along. No one really knows what they’re doing. Anyone who tells you otherwise is talking out of their butt.

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED TO CHARLIE KAHN—PART 1

I get home and shower the grease off myself, and before I’m even dressed, I pull Charlie’s cigar box from behind the bed and open it. I finger the yellow sealed envelope and still can’t bear to think about what’s in it. I open the next napkin, which he’d unfolded and printed on, in small block letters.

V

ALENTINE’S

D

AY

, J

ENNY WAS WAITING OUTSIDE

J

OHN’S HOUSE WHEN

I

CAME OUT

. S

HE TOLD ME THAT SHE WANTED TO GO OUT WITH ME BEHIND

C

ORSO’S BACK

. I

TRIED TO STAY FRIENDS WITH BOTH OF YOU, BUT

J

ENNY HATED YOU

. I

DON’T KNOW WHY, BUT SHE JUST HATED YOU

.

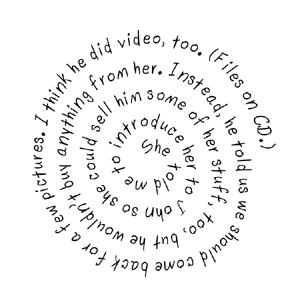

I say to myself, “No! You think?” The next napkin is written in a spiral, in tiny letters. The writing is becoming sloppy.

Okay.

I am completely grossed out.

I look at the clock and wonder what cop at the Mount Pitts police station would be willing to sit down and deal with this. Would they believe my side of the story, nearly nine months later? Would they pay attention because I had something to back it up, or blow it off to avoid the paperwork? Either way, I want Dad with me. I need him to help me do this, because even though earlier today I gave birth to myself, I am still a kid who needs his help.

I read on. The next napkin is written in all block letters again.

W

E ONLY MADE ABOUT

$100

FOR THEM

. I

T WAS NEVER ENOUGH FOR

J

ENNY

. J

OHN TOLD ME THAT HE WASN’T GOING TO DO IT ANYMORE, AND

I

WANTED TO GET AWAY FROM

J

ENNY, SO

I

BROKE UP WITH HER

. S

HE WENT FUCKING CRAZY

. S

HE SAID SHE’D GET ME ARRESTED FOR WHAT WE DID

. S

HE SAID SHE’D PUT ME IN JAIL

. S

HE SAID SHE’D GET

C

ORSO TO KILL ME

. T

HEN SHE SAID

SHE WAS GOING TO BURN DOWN THE STORE BECAUSE SHE HATES HER STEPDAD FOR MAKING HER WORK THERE

. S

HE SAID SHE WAS GOING TO TELL PEOPLE THAT I DID IT

. S

O

I

CAME TO YOU

. I

NEVER THOUGHT YOU’D ACTUALLY GO TO

Z

IMMERMAN’S

. I

DIDN’T KNOW WHAT TO DO

, V

ERA

. I

NEEDED SOMEONE TO KNOW THE TRUTH

.

HISTORY I’D RATHER FORGET—AGE SEVENTEEN—AUGUST (LAST ONE)

I lied to Dad and told him I’d forgotten to go to the office store for school supplies. Because he had to find a coupon from the morning’s paper, I was a little late.

It was 7:03 when I arrived. Zimmerman’s looked normal from the outside. I drove past first, and then parked between two pickup trucks. I didn’t see Charlie’s bike anywhere.

The “open/closed” sign on the door read

CLOSED

, even though they closed at eight on Sundays. The two sheltie pups in the front window seemed agitated. When I opened the door, the smell of gasoline overwhelmed me and I was instantly nervous that the whole place was going to explode any second.

“Hello?” I yelled. “Charlie?”

I took two steps in, but my legs refused to take me any farther. Then I saw Jenny, a small red gasoline canister in hand, ranting behind the glass in the reptile area. She tipped the spout into each cage and poured a trail of gas through the room. Then she saw me and her eyes bulged with the kind of insane evil you see in horror movies.

Right then, as my stomach moved into my throat and the gallons of adrenaline took over, everything went into shock mode. Everything looked different, everything sounded different. The animals even seemed to know what was going on. The birds to my right squawked and pecked on the bars of their cages. I heard the cats in the back hissing and the adoption center dogs barking danger barks. I’m pretty sure a lot of the fish were already floating. I didn’t see the usual darting of neon tetras, and the guppy tanks were all dark.

“Get out!” she screamed.

“Where’s Charlie?” I yelled.

“Charlie’s fucking dead.”

“Is he here?” I pictured him tied to a chair or something. The way she stood there, like a character in a Stephen King novel, she was capable of anything.

I’d been in the store for less than a minute so far, and it felt like an eternity. My whole body was shaking and I felt like throwing up. From what I saw, Charlie wasn’t there, but that didn’t stop me from worrying. (Only for a second did I think maybe he sent me on purpose. Only for a tiny millisecond did I imagine that he wanted me burned alive along with the multitude of helpless animals. Only for an itsy bitsy nanosecond did I suspect that they were working together to frame

me

for the whole thing.)

I was steps from the door and ready to bolt when twelve-year-old Vera kicked in. She reminded me that my mother abandoned me. She showed me pictures in my head of abandoned, charred puppies. She froze my legs.

I said to twelve-year-old Vera, “I can’t do anything for them! I don’t even have keys!”

Twelve-year-old Vera said, “But you

have

to do something!”

I said, “We have to get out of here!”

She said, “We have to save the animals!” and wouldn’t let my legs move.

I said, “Stop being so crazy! Can’t you see? I can’t do anything to save them!” It was true. I felt horrible about it and it sucked, but I couldn’t save them. I just couldn’t.

Twelve-year-old Vera sobbed in my head. I tried to mentally hug her. I said, “Sometimes there are no choices, Vera.” She answered by making me think of my mother again.

Before I could argue, I heard the backroom door slam shut, loudly, and it snapped me back to reality. Jenny Flick was about to burn the place down—and she didn’t care if I was in it or not.

Twelve-year-old Vera finally allowed me the use of my legs, and I pushed myself out the door.

When I got out, I felt dizzy from the fumes. I ran to my car and started it.

Shock warped time. When the clock on the stereo lit up, it said 7:07. It had only been four minutes since I parked, but it felt like an hour. I backed out of the parking space, drove to the farthest corner of the parking lot, and thought about calling 911, but called Charlie instead. The first two times it rang out and went to his voicemail, and I started to panic. (That would be panic inside of panic inside of panic.) The third time, he picked up.

“Dude!” I said. “She’s burning it down!”

“What?”

“Zimmerman’s!”

“You went?”

“Yeah!” My diaphragm was so jumpy, I had to catch my breath. I reached for a tissue. “Where are you?”

“Hiding.” I heard him cover the phone and heard muffled talking.

My concern for him turned into a mix of anger and embarrassment and disappointment and pretty much every bad emotion I could think of. Charlie Kahn had just dragged me into something so awful, I’d gone nearly schizo from it—and he wasn’t even in trouble. He was fine. Probably driving around, drinking beer.

“Are you still there?” I asked.

He was silent but for heavy breathing.

“Are you drunk?”

“Not yet.”

“Charlie, I—”

“I didn’t tell you everything, Vera.”

“It doesn’t matter. You need to go to the cops before she does.”

“Maybe I belong in jail.”

“Don’t say that.” What I meant was:

Oh my God, stop being such a drama queen

.

“No, Vera. Maybe I do. You don’t know what I’ve done.”

This just pissed me off. “Fine, Charlie. Do what you want.”

“I’ll write you a note or something. I’ll leave it where only you can find it.”

“What?” I said. What I meant was:

Say that again so you

can hear how stupid you sound

. Because that’s going too far, isn’t it? I mean, there’s a line between pathetic and dangerous, right?

“I’m going to leave you something,” he repeated—without an ounce of noticing how stupid he sounded.

I said, “Whatever,” and hung up.

I looked at the clock. 7:12. It felt like I’d been gone at least five hours already. I looked over at Zimmerman’s. So far, no fire. Still time to call 911, but rather than dial those three little numbers, I drove toward the mall exit because I wanted to get away from it all first. When the light turned green, I took a left and drove a minute up the strip, to the car wash. When I got there, I put the car in park and picked up my phone to call, but then I heard the fire station’s sirens, followed by fire engines and an ambulance racing down the main strip. Rather than get more involved than I already was, I rummaged through my purse to find a five-dollar bill, fed it to the machine, and drove my car into the auto wash until the buzzer sounded and the red light came on, directing me to stop.

When the car wash started, I thought I’d have a minute to lose myself in the loud darkness of it all. I thought I’d have a minute to work it all out—the right things to do—but I just sat and stared. I thought about those poor animals—were they going to be okay? I thought about Jenny, and wondered was she going to burn up in there, too? What happened to her to make her so crazy? Could Charlie breaking up with her really make her this mad?

As the auto wash soaped and rinsed the car, the thoughts continued. What would happen to Charlie? Would he go to jail? Would he be blamed for Jenny’s death? And what about the people in the mall? How many would die? Would he be blamed for that, too? If I told the truth, would anyone believe me? Why was I in this position anyway? How did I, after a lifetime of being safe and reasonable, end up

here?

When the unit switched off, I drove out into the lot and opened my window again to the sounds of chaos unfolding down at the Pagoda Mall, and I made my choice. Charlie Kahn had screwed me over enough. I would never trust him again, and I would forget this night had ever happened. I would pretend that I was just out buying school supplies. When the story came out and he got carted off to jail for life, I wouldn’t even wave. I was done.

The clock read 7:22. Suddenly the biggest thing on my mind was how I’d lied to Dad. I was worried that if I came home with no supplies, he’d think I was sneaking around doing something bad. So I drove to a completely different mall two miles in the opposite direction from the mall that was presently on fire. Ten minutes later, I was in line at Kmart, buying three spiral notebooks, a new calculator, a pack of unsharpened pencils, and a pack of Skittles. I felt people looking at me. I think I smelled like gas.

When I got home, it was past eight and Dad was reading in the den. I went inside and straight upstairs and took a shower. When the hot water hit my hair, I smelled the gas again. I said good night to Dad from the steps and I turned off the upstairs hall light and got into my bed and under the covers. I was still in complete shock. I tasted that weird metallic adrenaline in my mouth and my skin felt cold. I listened to the frogs and the crickets and the cicadas. I blocked out two overwhelming thoughts in my head—twelve-year-old Vera talking about the suffering animals and Charlie saying, “I’m going to leave you something”—and I tried to think about something positive. Senior year. My cool job. My bright future. An hour later, I was thinking about how there was no way I would ever fall asleep … when I fell asleep.

After a restless night of helpless-animal dreams, I woke up and went downstairs to find Dad crying on the couch. I’d never seen him cry before, not even when Mom left, so this was a big deal. He told me Charlie was dead. I didn’t understand. How did this happen? How could Charlie be dead?

“I didn’t get any details yet, Veer. Mrs. Kahn just told me he passed away last night sometime.”

I was still so numb from the night before, I found it hard to even fathom the fact of it. Charlie—dead. The worst part was, I couldn’t cry. As if I believed all the vowing and promising I’d done the night before never to care about Charlie Kahn again, I just couldn’t cry.

And then, Dad told me about the fire at the Pagoda Mall. I acted shocked. He showed me the newspaper article, and I was happy to learn that no one was dead or injured, aside from the animals (though many survived, including the nasty gray parrot and a lot of the adoption center animals, thanks to the sprinkler system and the fire-retaining walls between the pet areas).

As I sat pretending to read the story while Dad watched me, my mind wandered. Now I knew that Jenny Flick was not dead. But I knew that Charlie was. I just couldn’t understand this. Even if I said something right then about everything I knew, the wrong person had died and the wrong person had lived. I couldn’t help but feel like I’d been so busy arguing with twelve-year-old Vera about saving the animals that I overlooked that I could have saved human beings. Or—maybe just one human being.

Dad and I sat together for quite some time on the couch. We didn’t say anything. A few times, Dad reached out and held my hand. It seemed harder on him then than it was on me, and he told me, “I just can’t imagine what it must be like to lose a child. Please, Vera, be careful.” We each took a shower and tried to eat breakfast, but neither of us could swallow anything. I called off work for the day, and Dad canceled the only appointment he had, which was for a haircut.

We went over to the Kahns’ to offer our sympathy. They didn’t really make eye contact, and after ten minutes of saying we were sorry and telling them we were there if they needed us, we went back home. Dad made a big pot of chili for them while I took a walk.

I went to the pagoda first, but I couldn’t fly airplanes or even sit on the rocks because it’d been ruined by the Detentionheads. I wanted to walk to the Master Oak, but that was ruined, too, with Bill Corso’s big, ugly initials. The only place to go was the tree house, which was worse than either of the others, but something was telling me I had to go, so I did.

I didn’t go inside. I just sat on the octagonal deck, with my legs swinging over the edge. I read the old bumper sticker out loud. “The more I know people, the more I love my dog.” I finally cried.

They’d found him on the front lawn. They said he was probably pushed from a car. He’d landed folded into himself, so that when Mr. Kahn came out to go to work at 6:00, he saw a mystery lump in the front yard until he got close enough to see Charlie’s shoes. The ambulance didn’t put its lights or siren on. Dad and I slept through the whole thing, which was probably for the best. Nobody knew anything for sure yet, but it looked like Charlie might have died from alcohol poisoning or asphyxiating on his own vomit. His blood alcohol level was really high, and it looked like he was involved somehow with the fire at the Pagoda Mall. That’s what the Kahns told us. As they said these things, I pretended I wasn’t hearing them. My body and brain had gone into shock overdrive, where nothing made much sense. How was this happening? How could it be possible that after all that, Charlie was dead and Jenny Flick was still alive?

The Pagoda Mall closed until Halloween, when they opened a new, improved Zimmerman’s Pet Store. Before then, the newspaper ran a few articles about the fire, with details about how the deceased Charlie’s Zippo lighter was found at the scene. Stories went around town about how Jenny had broken up with him and he was so angry, he burned down the store to kill her. People said, “Thank God it wasn’t the school he burned down,” or “That boy was trouble from the start.” The Kahns had to go through a series of police interviews and in the end, no one went to jail. But no one knew the truth, either.

The night of the funeral, a pickle talked to me inside my head. It said, “Eat me and you will know the truth.” Sure, it was after I took those shots of vodka, but it did talk to me, and I did eat it. I’ve been waiting ever since.