Peeps at Many Lands: Ancient Rome (Yesterday's Classics) (9 page)

Read Peeps at Many Lands: Ancient Rome (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: James Baikie

Tags: #History

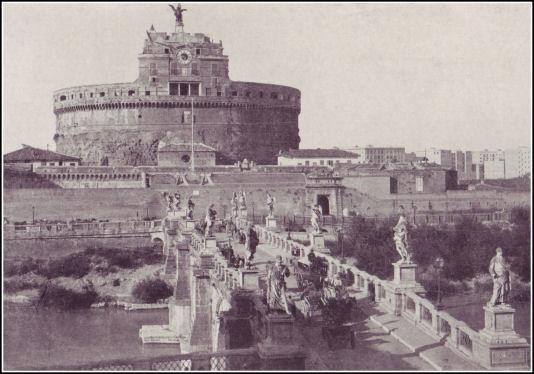

HADRIAN'S TOMB AND AELIAN BRIDGE

The triumph that we are about to witness is an imperial one, but it is no mockery, like that of Caligula or Nero. For the Emperor Vespasian and his noble son Titus have been in deadly wrestle with an enemy, not strong in numbers, but strong with all the courage of despair; and the siege of Jerusalem, which Titus has victoriously concluded, has been one of the most terrible in the long list of terrible sieges that the legions have carried through. There is every likelihood, too, that the Emperor and his son will make their triumph the most glorious that Rome has ever witnessed; for though Vespasian may be miserly, Titus knows the value of display in maintaining the popularity which he has known so well how to gain.

All the arrangements have now been made. The Emperor, with his two sons, Titus and Domitian, have been living beyond Tiber, outside the city walls; for, by ancient custom, no victorious general can pass the city gate until his claim has been granted, without forfeiting his right to the triumph. The Senate has met in the Portico of Octavia, beyond the river, to receive first the laurel-wreathed letter claiming the triumph, and then a visit from the Emperor and his son in person to plead their claim. Needless to say, when Cæsar pleads, his claim is never disregarded. The Senate has decreed a triumph, and it takes place to-day.

From early dawn the whole city has been astir. All thought of work is forgotten, and hundreds of thousands of Romans, young and old, rich and poor, are out in the streets, waiting for the coming of the great procession, and breaking, every now and then, into shouts of "Io Triumphe!" Some prefer to go far afield, and to meet the victors as they pass along the Via Triumphalis, beyond Tiber; some have a fancy for the corner where the procession, after passing the Forum Boarium, will turn sharp to the left along the Via Sacra to the great Forum; but we shall take our post just on the hither side of the river, and watch the long procession file slowly across the Triumphal Bridge. Then we shall transport ourselves, on shoes of swiftness, to the foot of the Capitoline hill, and see what happens when the earthly gods of Rome, Vespasian and Titus, go up to greet their heavenly brother Jupiter of the Capitol.

We are looking, then, across the bridge to the Triumphal Gate, through which the gay train must come. Cæsar and his sons have met once more with the Senate in the Portico of Octavia, have made solemn prayer to the gods, have tasted of the feast provided for the soldiers, and now, beyond the gate, they are offering sacrifice, and putting on the gold-embroidered purple robes that every triumphing victor must wear. Listen! That blast of trumpets means that the procession has begun to move, and through the gateway we see the city fathers coming first, with lictors accompanying them to clear the way. We have not come to see them, however, and the real show begins behind them.

A glitter of metal and a brazen blare from many trumpets heralds its approach. Here come the trumpeters, golden-helmeted and purple-clad, their great metal horns curling from their lips away underneath their arms, and then back over their shoulders, so that the wide mouths bellow triumph right ahead. And here, behind them, is something worth coming out to see—the spoil of all the long campaigns in Syria. Here are vessels of gold, and silver, and bronze, beaten and chased, ivory thrones and couches, carved with the most exquisite skill, and robes and tapestries of the most lovely fabric and the richest Tyrian dye. Now come all the treasures of the captured cities—diadems and necklaces, heaps of gold, and the flash and sparkle of innumerable jewels; so that, as the old Jewish historian says, it seems as though a river of treasure is flowing along the road, and people marvel that they ever held such things to be rarities. The legionaries who bear these riches are themselves gorgeously arrayed in tunics of purple silk, embroidered with gold.

Behind them come statues, in bronze, gold, and silver, borne on the shoulders of panting soldiers; and here are specimens of all the animals of Syria and the Arabian desert, with elephants harnessed for battle, and camels padding on their broad feet along the hard Roman way. But who are these that follow, gaily dressed, to grace the triumph, but belying their garb by their mournful bearing? Some, mostly the women or the children, are in tears; others tramp onwards looking straight before them with eyes that see nothing, in sullen desperation, while others look round upon the gaping and shouting throng with scorn and hatred written upon every line of their faces. These are the prisoners from Jerusalem, who defended their Holy City till famine drove tender mothers to devour their own children, and strong men fell dead of mere want at their posts, and pestilence raged unchecked, and the dead who lay unburied in the streets were more than the living in the houses or on the ramparts. Some of them, the youngest and the fairest, will be sold as slaves; some will be sent as oarsmen for the Roman fleet; and some will die in the arena in deadly conflict with one another, or with wild beasts. Small wonder that they have nothing but sad or bitter looks for Rome's day of triumph, as they think of what awaits them, and remember what they have lost, and their Holy and Beautiful House, now burned with fire.

Now, borne with difficulty by gangs of the brawniest men of the legions, come models of the conquered cities, followed by great panoramas of all the incidents in the campaign. Here you shall see the battles, the sieges, the alarums and excursions of the whole war rendered to the life—armies meeting in the shock of equal charge, the rout and the slaughter of the beaten host, the captives led away in chains, the drawing of the lines around a beleaguered city, the advance of the rams and catapults, towers crashing to the ground and burying helpless multitudes beneath their ruins, and above all the final sack and conflagration of Jerusalem—all painted with the most savage realism, to delight the cruel Roman spirit, that was never satisfied until it had supped full of horrors.

For some of us, the little group of trophies which follows this vulgar display of the horrors of war is infinitely more moving and suggestive—a golden table, a quaint seven-branched candlestick of gold, a few golden utensils for an altar, a number of silver trumpets, a great curtain of blue and purple and scarlet and fine twined linen, a rude pair of stone tablets incised with ancient script. For these are the relics of the Holy of Holies in God's House at Jerusalem never touched by unholy hands, or viewed by mortal eyes save those of an anointed High Priest of the line of Aaron. Now the basest scoundrel from the Suburra may jeer and mock at them. Behind them comes the man who could not save them—Simon, son of Gioras, bravest of the brave, but also most frantic of fanatics, who defended Jerusalem foot by foot and inch by inch with the most ferocious courage, fighting his enemy within the gates as savagely as he fought the foe without, and deaf to all the appeals of the Roman Prince to surrender on reasonable terms. Simon is dressed in black and laden with chains, and what remains of life for him is measured exactly by the time it will take this procession to pass from where we are standing to the foot of the Capitoline hill.

And now a thrill of expectancy passes over the vast crowd, for the ivory and gold statues of Victory have come in sight, and behind them, on two golden chariots, each drawn by four white horses, come the heroes of the day, Vespasian and his gallant son Titus; while his other son Domitian rides by his father's chariot on a magnificent charger. A thunderous shout of "Io Triumphe!" that shakes the very earth, heralds their appearance, and as the laurel-wreathed horses pace slowly by, we can gaze our fill at the men who have wiped the Holy City from the face of the earth. Vespasian, stout, vulgar-looking, and, in all probability, supremely contemptuous of the part he has to play, and greatly disgusted at the thought of what all this foolery is costing him, would probably already have fallen asleep, as he did, at the risk of his life, when Nero sang, were it not that his uncomfortable position in the jolting chariot makes sleep impossible. But Titus looks and plays his part to perfection.

He and his father are supposed to represent great Jupiter himself to-day, so he wears a purple toga bordered with gold like that which decks the great image in the temple on the Capitol. His arms are encircled by golden bracelets, his head crowned with a gilded laurel-wreath. Strangest of all, since Jupiter Capitolinus is painted vermilion, Titus must needs "paint an inch thick to imitate great Jove," and his hands and his handsome features are disfigured with a thick daubing of red paint—the Roman had a strong taint of ancient and incurable barbarism at his heart, even when he fancied himself the heir of all the ages. In his red hand Titus holds an ivory sceptre surmounted by a golden eagle, and his nodding steeds are led by a purple-clad and golden-helmeted girl who represents Roma. Behind the victor Prince, on the step of the chariot, stands a slave, who every now and then bends forward and whispers in his master's ear, "Cæsar, remember that thou also art a man!" Yes, even in the midst of such glory, a man, doomed to die, like Simon, who must die so soon!

The conquerors pass, and the shouts roll away like thunder through the Triumphal Gate. And now the army follows, in endless procession, chanting rough camp-fire songs, and shouting rude jests at the expense of its commanders; for all is permitted on this day of joy and licence. Meanwhile we use our shoes of swiftness to bring us to the foot of the Capitoline hill. At the top of the marble stairway above us towers the triple colonnade, splendid with purple and gold, of the great Temple of Jupiter. Vespasian and Titus alight from their chariots and slowly mount the steps towards the portico; but they do not enter the temple—yet. One small ceremony, surely worthy of such mighty conquerors, has still to be performed.

The lictors advance upon the black-robed Simon, and lay rough hands upon him. He is led away into the Forum, and there he is scourged with savage cruelty. Dripping with blood, and already half dead, he is dragged remorselessly to the gloomy Mamertine dungeon which lies beneath the gorgeous temple where his victors wait. Simon is cast down headlong into the hideous underground cell, the Tullianum, where so many famous enemies of Rome have gasped out their lives. An executioner awaits him, and the axe quickly ends his agony. The poor mangled body is dragged away and flung into the Tiber. Did we not say that the Roman remained in some things a barbarian to the very last?

Above, within the portico of the temple, the victors wait. A lictor hastens up the steps, and, bowing low before his lords, he utters a single word—"Vixit" (He has lived). Simon is dead, then, and the two gods on earth, having completed so noble a work, may safely enter the presence of their brother, the God of Heaven. They pass into the sanctuary and bow in thanksgiving and praise before the image of great Jove. Then Titus places in the hand of the god a branch of laurel, and lays his golden diadem upon the divine knees in token that all the chiefest of the spoil shall belong to Jupiter; and the day ends with sacrifices innumerable and Gargantuan feasting through the whole city. Rome is ablaze with lights and ringing with rejoicing; and Simon's mutilated corpse drifts seaward down the muddy Tiber, a witness to heaven and earth against the hearts of stone that even in triumph and joy could not remember mercy.

The Games: The Circus Maximus

T

HE

Romans, as I dare say you know already, were always passionately fond of their games. From the earliest to the latest days of their history it was always the same with them, and we know that the games had been a regularly established event in the city year, with high officials specially appointed to attend to them, for nearly 400 years before the fall of the Republic and the coming of the Empire. Under the emperors the passion for such amusements grew continually. It came to be no longer a question of games on a few great festival occasions every year, but on every possible opportunity. The only way to keep the turbulent rabble of Rome in good temper was to give them constantly free bread and free games; and the cry, "Bread and the games!" was one to which no ruler of Rome who valued his popularity ever dared to turn a deaf ear.

You must know, however, that what a Roman meant by "games" was something very different from our harmless contests in wrestling, running, and leaping, or even from the sterner conflicts of the great Greek athletic festivals. The only Roman game that was even comparatively harmless was the chariot-race, and even then the drivers ran a good risk of having their necks broken. The real "game" was to see men killing and being killed—gladiators hacking and thrusting at one another, wild beasts being attacked by men whose miserable weapons were only sufficient to provoke the creatures to fury and make them turn upon their hunters with greater savagery, sea-fights in some great artificial lake, where slaves dashed galley against galley in some mimic Salamis or Mylæ, till the waters were red with blood. Such things the fierce Roman nature always loved to see, and the thirst for blood grew year by year, till the Roman games were horrors that cannot be described.