Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies (69 page)

Read Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies Online

Authors: Catherine E. Burns,Beth Richardson,Cpnp Rn Dns Beth Richardson,Margaret Brady

Tags: #Medical, #Health Care Delivery, #Nursing, #Pediatric & Neonatal, #Pediatrics

Treatment of type 1 diabetes in children has a strong evidence base. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, 1993, 1994) clearly demonstrated that tight glycemic control achieved through intensive insulin therapy is critical in preventing or forestalling long-term complications of diabetes. The Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Study (White et al., 2001; Writing Team for the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, 2002), a prospective epidemiologic study of DCCT participants, provides ongoing evidence that the improved metabolic control achieved for those in the intensively treated group remains protective against the long-term complications of diabetes. Application of DCCT findings to pediatric patients was initially cautious because of risk of hypoglycemia (DCCT Research Group, 1994) and safety of intensive insulin regimens when young children were away from parental supervision. Recent reports (Churchill, Ruppe, & Smaldone, 2009; DiMeglio et al., 2004; Fox, Buckloh, Smith, Wysocki, & Mauras, 2005; Jeha et al., 2005; Litton et al., 2002; Mack-Fogg, Orlowski, & Jospe, 2005; Wilson et al., 2005) provide evidence that intensive insulin regimens are both safe and efficacious, even when used in young children. Current American Diabetes Association standards of care for children with type 1 diabetes (Silverstein et al., 2005) reflect both lower glycemic targets and intensive insulin regimens using multiple daily injections or insulin pump therapy as the means to achieve them.

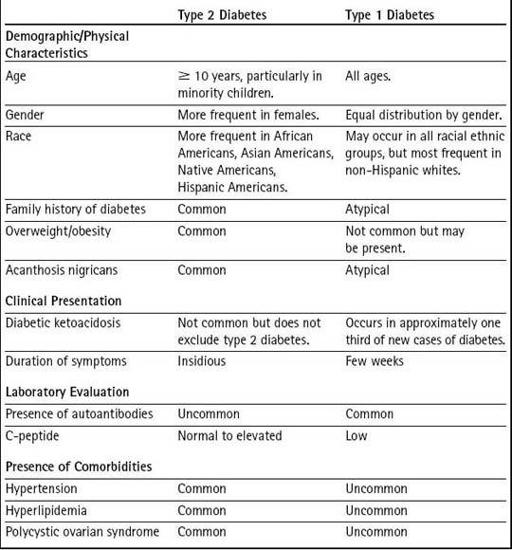

There is no diagnostic test to differentiate type 2 from type 1 diabetes; further, some features of diabetes formerly thought to be present only in type 1 diabetes (e.g., diabetic ketoacidosis and presence of autoantibodies) are now recognized as not being exclusive to one type of diabetes.

Table 18-3

examines demographic, laboratory, and comorbidity factors and their frequency in type 1 and type 2 diabetes in childhood. The presence of a factor does not confirm or exclude one type of diabetes; however, a particular factor may occur more frequently in type 1 or type 2 diabetes (Dabelea et al., 2007).

Table 18–3 Differentiating Type 2 from Type 1 Diabetes

Rethinking Mary’s Diabetes Diagnosis

Hospital records document that Mary presented to the hospital emergency room with persistent vomiting, polyuria, and excessive thirst. She had been ill for the past 2 days. Her past medical history was uneventful and her prior health described as excellent. Although sluggish, she was oriented to time, person, and place. On physical examination her pulse was 108, respirations 30, temperature 37°C (98.6°F), blood pressure 130/90, and weight 142 lbs. Lungs were clear to auscultation, heart sounds were normal, and abdomen was soft without hepatosplenomegaly. Mary’s initial laboratory evaluation included a basic metabolic panel, venous blood gas, complete blood count, and urinalysis. Subsequent laboratory evaluation included hemoglobin A1c and islet cell antibody (ICA) and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) titers.

Notable among Mary’s laboratory results, blood glucose was reported as 500 mg/dL (reference range 60–100 mg/dL), serum sodium 128 mEq/L (reference range 133–146 mEq/L), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 40 mg/dL (reference range 5–26 mg/dL). Venous blood gas results were indicative of a metabolic acidosis with pH 7.12 and pCO

2

10. Urinalysis results demonstrated specific gravity > 1.030, large glucose, and large ketones. Hemoglobin A1c was 12% (reference range < 6%) and ICA and GAD antibodies were reported as negative.

She was admitted to the intensive care unit for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) management, which included fluid resuscitation with normal saline to restore fluid balance, titration of blood glucose using an insulin infusion drip, and potassium replacement. No sodium bicarbonate was given. She remained in the intensive care unit for 36 hours, was discharged to a pediatric hospital unit for diabetes education, and was subsequently discharged to her aunt’s home. The hospital discharge note indicated uncertainty regarding type of diabetes, a nonspecific plan for follow-up care in the child’s community, and pending results of ICA and GAD antibody levels.

Making the Diagnosis

After thorough review of the pathophysiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes, the history and physical examination data, and Mary’s hospital records, you begin to rethink Mary’s initial diabetes diagnosis. Following review of Mary’s family history and hospital laboratory data with your collaborating physician, you conclude that Mary has type 2 diabetes. Her laboratory results on hospital admission definitively document diabetes (blood glucose 500 mg/dL with symptoms of polyuria and polydipsia) (see

Table 18-2

) and presence of diabetic ketoacidosis (blood glucose 500 mg/dL, low serum pH, and low CO

2

) (Frazier & Pruette, 2009; National High Blood Pressure Education Program, 2004). Her strong family history of type 2 diabetes, age, race, and negative ICA and GAD antibody status help to clarify her type of diabetes as type 2.

Table 18-3

compares characteristics of children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Management

Mary returns accompanied by her mother for her 2-week follow-up visit since her last visit with you. Mary has been well and brings blood glucose records with her today. She states that she has not had many low blood glucose readings and that she has been eating an apple for a snack instead of chips if she is hungry between meals. Her weight today is 147 pounds (3-pound weight loss) and blood pressure is 122/78 (90th percentile for age and height (Frazier & Pruette, 2009). Her blood glucose records show that most readings are in a range of 80–140, with occasional episodes of hypoglycemia after softball games.

Managing a teenager with diabetes is complex. Fortunately, a great deal of work has been done in this area that can help you develop a complete long-term healthcare plan.

Goals of Therapy

First, you need to establish goals for your care as well as goals for Mary and her family to achieve. Treatment goals for the adolescent diagnosed with type 2 diabetes are the following:

• Maintain blood glucose values as close to a normal range as possible while minimizing hypoglycemic episodes.

• Maintain hemoglobin A1c values at ≤ 7%.

• Prevent and/or identify comorbidities of diabetes and long-term microvascular complications of diabetes.

• Promote normal growth and development.

• Promote weight loss.

• Engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Treatment Options

Although diabetes treatment and education approaches for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes are well defined and supported by findings of the Diabetes Complications and Control Trial (DCCT) (DCCT Research Group, 1993, 1994), treatment of type 2 diabetes in youth remains in its infancy and currently lacks a strong evidence base. The TODAY Study, a multi-center randomized controlled trial presently in progress, was designed to identify the best “Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth.” (Information about the TODAY Study may be accessed online at

http://www.todaystudy.org/index.cgi

.) The study is comparing the effectiveness of three treatment options for youth with type 2 diabetes: 1) metformin (currently the only oral diabetes agent approved for use in children), 2) metformin plus rosiglitazone, and 3) metformin plus an intensive behavioral intervention (Zeitler et al., 2007).

Medication Management

The hallmark of management of children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes is instituting a change from unhealthy to healthy nutritional and physical activity behaviors leading to weight loss. In the United States, fewer than 10% of individuals with type 2 diabetes are successful in achieving glycemic control with diet and exercise alone. Therefore, pharmacologic therapy is recommended in addition to diet and exercise.

Although a wide variety of medication choices are currently available for management of type 2 diabetes, metformin and insulin are the only medications currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the pediatric population (Atkinson & Radjenovic, 2007; Zeitler et al., 2007). However, because the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents is similar to that of adults, recent advances in different classes of medications for adults with type 2 diabetes have led to their off label use in children. Therefore, it is important that health professionals are well versed in the medications used in their particular setting.

Oral medications used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes lower blood glucose levels by increasing sensitivity to insulin (biguanides, thiazolidenediones, α-glucosidase inhibitors) or increasing insulin secretion (sulfonylureas, meglitinides) (Ludwig & Ebbeling, 2001). Over time, the natural course of type 2 diabetes will result in the body’s inability to produce sufficient insulin and insulin replacement so that long- and/or short-acting insulin will be necessary.

Metformin, a biguanide, is recommended as the initial drug of choice in management of type 2 diabetes in adolescents. Metformin improves blood glucose levels without risk of hypoglycemia, and treatment is associated with a mild decrease in weight and decrease in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and triglyceride levels. In girls with irregular menses or polycystic ovarian syndrome, treatment with metformin may also improve ovarian abnormalities and, therefore, increase the risk of unplanned pregnancy (American Diabetes Association, 2000). Metformin is contraindicated in patients with impaired renal function or hepatic disease, and treatment should be temporarily discontinued during any illness accompanied by dehydration or hypoxemia because of risk of lactic acidosis (American Diabetes Association). If monotherapy with metformin is unsuccessful in achieving glycemic targets, an agent from a different class or insulin may be added to the therapeutic regimen.

Medication may also be prescribed to control hypertension (National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group, 2004; Tan, 2009) and dyslipidemia, two frequent comorbidities of type 2 diabetes in youth. Guidelines for treatment of dyslipidemia in pediatric patients were recently amended to include children 8 years of age or older, particularly when accompanied by other cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity or diabetes (Daniels & Greer, 2008).

Children and families should receive both verbal and written instruction for each prescribed medication including purpose, dose, frequency, and potential side effects. It can be helpful to write medication changes in the blood glucose diary as an additional daily reminder. Medication adherence should not be assumed; it is important that adherence be assessed routinely at each patient encounter, particularly during adolescence.

Nutritional Changes

Healthful eating, in terms of both nutritional value and portion size, and improving physical activity are important components of the treatment plan for youth with type 2 diabetes. At diagnosis, the family should meet with a dietician experienced in nutritional management of children with diabetes to receive individualized, culturally appropriate medical nutrition therapy to achieve diabetes treatment goals, prevent cardiovascular disease, and promote behavior change (Gidding et al., 2005). Medical nutrition therapy recommendations should be reviewed with families at least yearly. Modest weight loss has been shown to decrease insulin resistance (American Diabetes Association, 2008). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently launched a “Healthy Weight” Web site (

http://www.cdc.govhealthyweight/index.htm

)

that provides nutrition information geared to parents and a site with interactive games specifically designed to promote healthy food choices and physical activity for children (

http://www.smallstep.gov/kids/flash/index.html

).

Physical Activity Changes

It is recommended that adolescents engage in 60 minutes of physical activity most days of the week (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). Physical activity has multiple benefits for the child or adolescent with type 2 diabetes. In addition to lowering blood glucose levels, activity helps to burn fat, increase insulin sensitivity, and increase energy expenditure, and has beneficial effects on blood pressure and lipid levels. Because of their more sedentary lifestyle pattern, many children/adolescents with type 2 diabetes may need ongoing encouragement to initiate an exercise program and should be counseled to start slowly, gradually increase intensity, and build physical activity into lifetime habits. Overweight or obese adolescents may lack self-esteem or motivation to participate in school sports activities but may be willing to walk as a form of exercise. Use of pedometers has been effective in improving physical activity levels in adolescents, particularly when individualized behavioral goals are set (Butcher, Fairclough, Stratton, & Richardson, 2007; Schofield, Mummery, & Schofield, 2005).