Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies (135 page)

Read Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies Online

Authors: Catherine E. Burns,Beth Richardson,Cpnp Rn Dns Beth Richardson,Margaret Brady

Tags: #Medical, #Health Care Delivery, #Nursing, #Pediatric & Neonatal, #Pediatrics

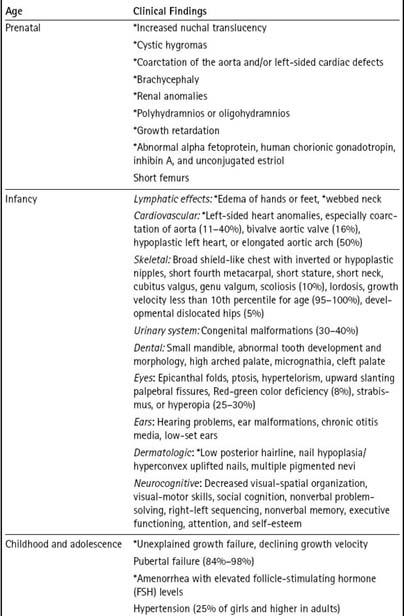

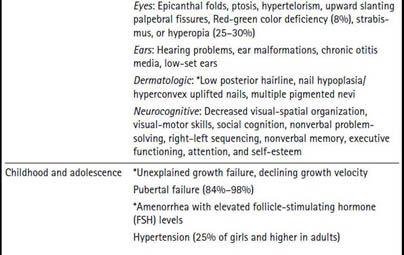

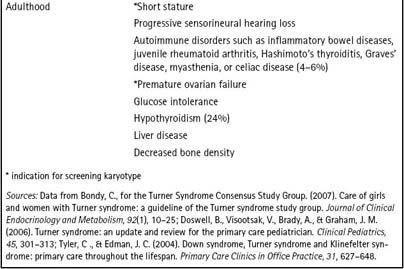

As adults, women with Turner syndrome can have health problems such as obesity, and autoimmune issues such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, and inflammatory bowel disease. High-frequency hearing loss occurs in about 25% to 66% of individuals (see

Table 34-1

).

Epidemiology

Turner syndrome occurs in approximately 1 in 2,000 to 3,000 live female infant births (Frias, Davenport, Committee on Genetics, & Section on Endocrinology, 2003; Nielsen & Wohlert, 1991). It is thought to occur in about 1–2% of all conceptuses; however, the majority of these are spontaneously lost in the first trimester of pregnancy. The retained X chromosome can come from either parent (Tsezou et al., 1999).

Differential Diagnoses

Although Turner syndrome is classically the most common syndrome associated with young women with short stature, it should be noted that Noonan syndrome also presents with similar findings, including poor growth, congenital heart malformations, short stature, renal problems, learning problems, pectus excavatum, impaired blood clotting, webbed neck, low hairline, low-set ears, and scoliosis. This syndrome may occur in males or females. It is caused by genetic mutations of chromosome 12q24.1, including genes PTPN11, KRAS, and RAF1. The karyotype is different from that of Turner syndrome.

Table 34–1 Common Clinical Findings in Turner Syndrome

Making the Diagnosis

What test will you order to make the diagnosis of Turner syndrome or another chromosomal condition?

Diagnostic Testing

The diagnosis of Turner syndrome is confirmed by obtaining high-resolution chromosome studies.

You discuss the possibility of a genetic cause for Jane’s short stature and kidney problem with Jane and her mother. They agree to testing and you send them off for high resolution chromosome studies. The results shows a 45, X karyotype as you suspected.

You might choose to call a geneticist and consult with him or her regarding testing at this point or make a referral and then let that person decide what studies are necessary. In this case, you are fairly confident about the diagnosis and a karyotype is a basic genetics test. Other diagnoses might require considerably more studies including metabolic assays and others. In that case, given the expense, it would probably be better to send the child off and let appropriate studies be ordered from there.

Management

How will you begin management of this child with the genetic condition of Turner syndrome?

Because genetic conditions do not occur very often in your daily primary care practice, you go online to see if there are guidelines for care of these children prepared by experts from across the country. The National Institutes of Health and the American Academy of Pediatrics are good places to start. Online, you quickly find that guidelines have been developed by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and Turner Syndrome Consensus Study Group (Bondy, 2007). Earlier guidelines were published in 2003 by the American Academy of Pediatrics (Frias et al., 2003). You feel prepared now for the Murphys’ return visit.

Jane and her mother return to the clinic to learn the results of the chromosome studies. You tell them what the syndrome is and explain that the condition was not the fault of either parent. Turner syndrome is caused by a loss of an X chromosome, so the underlying chromosomal defect cannot be repaired. However, there are a variety of treatments that can positively affect the symptoms of the genetic disorder, including help with her short stature.

Management of Turner Syndrome

Your management plan generally follows the national guidelines. Here is the information you learned from your study before seeing the family.

Short Stature

Short stature is one of the most common findings associated with Turner syndrome, affecting almost all of the girls with this diagnosis. The mean final height in untreated women is 143 cm, or only 4’ 9” (57 inches). Growth hormone has been approved for the treatment of short stature and is considered the standard of care for a child with Turner syndrome. The best time for it to be started would be when the child’s height falls below the fifth percentile. For approximately 50% of girls, that would occur between 2 and 3 years of age. Starting children on growth hormone at an early age is important, because gains of 8 to 10 centimeters (about 3 to 4 inches) have been noted if individuals receive at least 6 years of growth hormone (Bondy, 2007; Tsezou et al., 1999).

Starting Jane on growth hormone at age 10 years will not give her as much additional height as it would had she been started at age 2 or 3 years, but some increase in growth velocity and final height can be anticipated.

Cardiovascular Issues

Jane requires a cardiovascular evaluation, although her murmur sounds innocent. Even if there is no evidence of a murmur, all children with the diagnosis

of Turner syndrome should be evaluated by a cardiologist and have an echocardiogram, an ECG, and other studies as necessary. Cardiovascular anomalies are thought to occur in 20% to 40% of affected individuals or more, and many of these congenital heart problems can be repaired through intervention. Hypertension occurs in about 25% of girls and is an important risk factor for dissecting aneurysms, another health problem for Turner syndrome patients (Bondy, 2007).

Endocrinology

An endocrine evaluation is extremely useful because gonadal dysgenesis is common (90%) in Turner syndrome (Doswell et al., 2006). Many girls will require sex hormone replacement in order to begin puberty. It should be noted that a variety of issues are associated with sex hormone replacement. It can be initiated early in some individuals, whereas other individuals who are still working on gaining height may have their estrogen therapy delayed until as late as 15 years of age to allow them to achieve their maximum height potential. Although secondary sexual characteristics can develop in individuals with mosaicism, even those individuals should have their endocrine system evaluated because they may also require estrogen therapy.

In the majority of cases, individuals with Turner syndrome are not able to bear children. It is the responsibility of the primary care provider to discuss reproductive options such as adoption or medically assisted reproduction with individuals who have this diagnosis when they are at an age for comprehension. Occasionally, a rare individual may have sufficient ovarian function to ovulate and may become pregnant; however, there is an increased risk of fetal chromosomal abnormalities or miscarriages in such women so genetic counseling is important. Pregnancy with a donated egg is more commonly achieved (Doswell et al., 2006).

Neurocognitive Issues

Many individuals with Turner syndrome have a specific set of cognitive functioning differences in the areas of decreased visual-spatial organization, social cognition, nonverbal problem-solving, right-left sequencing, executive function, attention, and self-esteem (Bondy, 2007; Doswell et al., 2006; McCauley et al., 1995; Romans, Stefanatus, Roeltgen, Kushner, & Ross, 1998; Ross, Zinn, & McCauley, 2000).

Psychosocial Support

It is important for the primary care provider to assess the psychological support that is available to the child and family. Involvement with local Turner syndrome support groups or the Turner Syndrome Society of the United States (

http://www.turnersyndrome.org

) is a way of allowing individuals to interact with other families who have similar problems. Literature should be supplied to the family about Turner syndrome, and other resources should be available

including therapy resources if they are needed. The American Academy for Pediatrics provides information for medical providers.

Genetics Issues

Genetic conditions, as do other chronic conditions, affect families for many years, influencing decisions about childbearing, health care, social relationships, finances for health insurance, and many other aspects of life. Consultation with a genetics clinic or geneticist can be very helpful in answering a family’s questions.

Other Healthcare Needs

A variety of other abnormalities are associated with Turner syndrome, including hearing loss, strabismus, obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertension, thyroid dysfunction, orthopedic issues, and urinary tract abnormalities, among others. Each of these systems needs to be evaluated in a child with Turner syndrome, and appropriate referrals will need to be made (Bondy, 2007; Donaldson, Gault, Tan, & Dunger, 2006; Doswell et al., 2006; Tyler & Edman, 2004).

Given the national guidelines for treatment of girls with Turner syndrome (Bondy, 2007), you talk with the family to describe the plan and rationale for each step. You arrange for her:

Referrals for care: