Pediatric Examination and Board Review (117 page)

Read Pediatric Examination and Board Review Online

Authors: Robert Daum,Jason Canel

5.

(D)

Among African American youth age 15-19 years, suicide rates in boys are more than 6 times higher than girls.

6.

(E)

A comprehensive physical examination of an adolescent should include the following:

• Height, weight, BP, and heart rate

• Growth assessment, plotting height, weight, growth velocity, and calculated BMI in the corresponding growth charts

• Skin examination

• Eyes, ears, nose, and throat, dental and gum examination

• Neck examination for thyromegaly or other adenopathy

• Cardiopulmonary examination

• Abdominal examination

• Genital examination and assessment of sexual maturity rating

• Breast examination

• Musculoskeletal examination

• Neurologic examination

• Vision and hearing screening

7.

(C)

According to the American Medical Association’s GAPS, adolescents should have a comprehensive examination once during early adolescence (age 11-14 years), once during middle adolescence (age 15-17 years), and once during late adolescence (age 18-21 years). These guidelines also recommend that BP and BMI be monitored yearly.

8.

(C)

A pelvic examination should be performed in adolescents with gynecologic complaints such as pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, or severe menstrual bleeding. Sexually active adolescents should also be examined to exclude STDs. However, a pelvic examination is not indicated before prescribing contraceptives in the asymptomatic, nonsexually active teen. According to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and National Cancer Institute, a pelvic examination including pap smear is not needed until age 21 in asymptomatic women who have not become sexually active, or within 3 years of initiating sexual activity before 21 years old. Most cases of primary dysmenorrhea are functional and, if the clinical history is highly suggestive of that diagnosis, a pelvic examination is not required.

9.

(C)

Despite the fact that the patient denies sexual activity, it would be prudent to document that pregnancy has been excluded as a cause of secondary amenorrhea. This should be discussed with the patient and her consent should be obtained before performing the test. Up to 50% of adolescent girls have physiologic irregular menses for the first 12-24 months, secondary to having anovulatory cycles.

10.

(C)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revised its HIV screening recommendations in 2006, and it now recommends annual HIV screening for patients 13-64 years old unless the practice area has a documented prevalence of undiagnosed HIV cases of less than 0.1%. Otherwise, there are no other universal recommendations regarding laboratory screening tests in asymptomatic adolescents. Several national organizations have published screening guidelines but vary widely in their advice. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends baseline anemia screening, neither the American Medical Association (AMA), Bright Futures, nor the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force endorses that view. An anemia screen would be indicated in an adolescent girl if the clinical history reveals inadequate diet or frequent or heavy periods. Cholesterol screening is performed in all adolescents with a family history of premature cardiovascular disease or hyperlipidemia. Screening for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis is recommended at least annually for sexually active teens. Diabetes screening is recommended for those with BMI higher than 85% and a family history of an immediate relative with diabetes.

11.

(A)

She should be immunized against varicella. Two doses, at least 1 month apart, are given to adolescents 13 years and older. Alternatively, varicella titers could be obtained followed by immunization if the titers are negative. Serologic testing is unnecessary after immunization given the high rates of seroconversion with the use of the vaccine. Varicella vaccination is not contraindicated in household members of immunocompromised patients, including those with HIV infection. Immunized persons who develop a rash should avoid contact with immunocompromised susceptible hosts for the duration of the rash.

12.

(B)

Tuberculin testing should be considered positive in children 4 years and older without any risk factors if the area of induration measures more than 15 mm. With an induration of 8 mm it will be important to determine whether this teen has been in close contact with a known or suspected contagious case of active or previously active tuberculosis, either untreated or inadequately treated before the exposure took place. This result would only be interpreted as positive in teens receiving immunosuppressive therapy or those with immunosuppressive conditions including HIV. The interpretation of a positive tuberculin skin test should not be influenced by a previous history of BCG administration.

13.

(D)

Previous BCG administration is not a contraindication to tuberculosis skin testing. Moreover, disease caused by

M tuberculosis

should be suspected in any symptomatic patient with a positive PPD, regardless of the history of BCG immunization. In the asymptomatic teen who has received BCG, the interpretation of a positive PPD should include consideration of the following factors: exposure to a person with contagious tuberculosis, family history of tuberculosis, immigration from a country with high prevalence of the disease, and a PPD reaction more than of 15 mm. These factors strongly suggest actual infection. Prompt radiographic evaluation of all teens with a positive PPD test is recommended regardless of their BCG immunization status.

14.

(D)

During the well-adolescent visit, the primary care provider has an invaluable opportunity to discuss a number of preventive health-care issues including sexual activity and its consequences. After establishing an initial rapport and adequate communication with the patient and family, the physician can elicit any questions or concerns the patient may have regarding sexuality. Pregnancy and STD prevention can then be addressed, tailoring the discussion to the teen’s level of cognitive and emotional development and to his or her sociocultural background. Knowing that in the United States approximately 30% of adolescent girls are already sexually active by ninth grade and that this percentage more than doubles by twelfth grade, it is essential to discuss pregnancy prevention, including abstinence, barrier, and hormonal methods early during adolescence. Similarly, at any given time, approximately 25% of all teens 15-19 years old have an STD.

15.

(E)

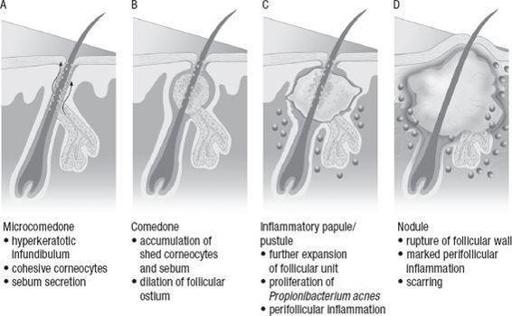

Acne vulgaris is the most common skin disorder in the United States (see

Figure 71-1

). The prevalence of comedones during adolescence approaches 100%. Four pathogenic factors play a major role in this condition: (1) retention hyperkeratosis, (2) increased sebum production, (3) proliferation of

P acnes

within the pilosebaceous follicle, and (4) inflammation. Follicular hyperkeratinization with increased proliferation and decreased desquamation of the keratinocytes lining the follicular orifice lead to the formation of a hyperkeratotic plug (a combination of sebum and keratin in the follicular canal). During adrenarche, there is an increased production of sebum as sebaceous glands enlarge.

P acnes

organisms thrive in the presence of increased sebum, hydrolyzing triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerol, which in turn, together with other factors, leads to local inflammation. According to the extent of follicular hyperkeratinization, sebum production,

P acnes

growth, and inflammation, the initial microcomedo will evolve into a noninflammatory closed comedo, an open comedo, or an inflammatory pustule, papular, or nodular lesion. Dietary factors play no role in the development of acne.

FIGURE 71-1.

A

-

D

acne pathogenesis. (Reproduced, with permission, from Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008: Fig. 78-1.)

16.

(B)

Comedolytic agents such as benzoyl peroxide and retinoids help to prevent and/or decrease keratinocyte proliferation and retention. Initial management of mild comedonal acne includes topical 5% benzoyl peroxide gel or 0.025% tretinoin topical once daily.

17.

(D)

It would be advisable to monitor acne treatment 3 months after initiating topical medication, stressing the need for consistent, long-term compliance to achieve adequate therapeutic results.

S

S

UGGESTED

R

EADING

An overview of minors’ consent law. Guttmacher Institute Web site.

http://www.guttmacher.org/sections/adolescents.php

. Accessed September 2009.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings.

MMWR.

2006;55(RR14):1-17.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years. United States.

MMWR

. 2010;58(51&52).

Guide to Clinical Preventive Services

. Washington, DC: United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); 2009.

Guidelines for adolescent preventive services. American Medical Association Web site.

http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/1980.html

. Accessed September 2009.

Joffe A, Blythe MJ. Handbook of adolescent medicine.

Adolesc Med.

2003;14:2.

Krowchuk DP, Lucky AW. Managing adolescent acne.

Adolesc Med.

2001;12:355-374.

Maternal and Child Health Bureau.

U.S. Public Health Services (MCHB)—Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Care Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents

. 1994. Bright Futures Web site.

http://www.brightfutures.org

. Accessed September 2009.

Neinstein LS.

Adolescent Health Care

.

A Practical Guide.

5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS.

Red Book

2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases.

28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009.

Ten leading causes of death and injury by age. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site.

http://www.cdc.gov/injury/ wisqars/LeadingCauses.html

. Accessed September 2009.

CASE 72: A 15-YEAR-OLD BOY WITH SHORT STATURE AND PUBERTAL DELAY