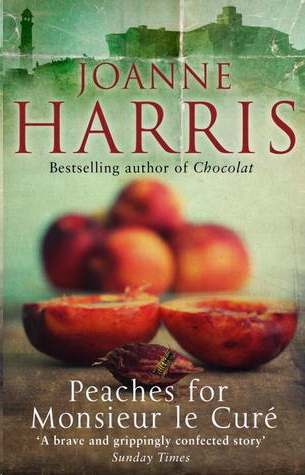

Peaches for Monsieur Le Curé

About the Book

It isn’t often you receive a letter from the dead.

When Vianne Rocher receives a letter from beyond the grave, she has no choice but to follow the wind that blows her back to Lansquenet, the village in south-west France where, eight years ago, she opened up a chocolate shop.

But Vianne is completely unprepared for what she finds there. Women veiled in black, the scent of spices and peppermint tea, and there, on the bank of the river Tannes, facing the square little tower of the church of Saint-Jérôme like a piece on a chessboard – slender, bone-white and crowned with a silver crescent moon – a minaret.

Nor is it only the incomers from North Africa who have brought big changes to the community. Father Reynaud, Vianne’s erstwhile adversary, is now disgraced and under threat. Could it be that Vianne is the only one who can save him?

Contents

PEACHES FOR

MONSIEUR LE CURÉ

Joanne Harris

To my father, Bob Short, who would never let good fruit go to waste.

CHAPTER ONE

SOMEONE ONCE TOLD

me that, in France alone, a quarter of a million letters are delivered every year to the dead.

What she didn’t tell me is that sometimes the dead write back.

CHAPTER TWO

Tuesday, 10th August

IT CAME ON

the wind of Ramadan. Not that I knew it then, of course. Paris gets windy in August, and the dust makes little dervishes that skate and scour the sidewalks and leave little sparkling flakes of grit on your eyelids and your face, while the sun glares down like a blind white eye and no one feels like eating. Paris is mostly dead right now, except for tourists and people like us who can’t afford a holiday; and the river stinks, and there is no shade, and you’d do almost anything to walk barefoot in a field somewhere, or to sit under a tree in a wood.

Roux knows how it is, of course. Roux wasn’t made for city life. And when Rosette is bored she makes mischief; and I make chocolates for no one to buy, and Anouk goes to the internet café on the Rue de la Paix to talk with her friends on Facebook, or walks up to Montmartre cemetery and watches the feral cats that slink among the houses of the dead, with the sun coming down like a guillotine between the slices of shadow.

Anouk at fifteen. Where does the time go? Like perfume in a bottle, however tight the seal, evaporating so slyly that, when you open it to look, all you find is a scented smear where once there was enough to spare—

How are you, my little Anouk? What’s happening in your strange little world? Are you happy? Restless? Content? How many more of these days will we have before you leave my orbit for good, shooting away like a rogue satellite, vanishing into the stars?

This train of thought is far from new. Fear has been my shadow ever since Anouk was born, but this summer the fear has grown, blooming monstrously in the heat. Perhaps it’s because of the mother I lost – and the one I found four years ago. Or maybe it’s the memory of Zozie de l’Alba, the taker of hearts, who almost robbed me of everything, and who showed me how fragile our lives can be; how easily the house of cards can fall at the smallest breath of wind.

Fifteen.

Fifteen

. At her age I’d already travelled the world. My mother was dying. The word

home

meant any place we stayed for the night. I’d never made a real friend. And love – well, love was like the torches that burn at the terraces of cafés at night; a source of fleeting warmth; a touch; a face half glimpsed in firelight.

Anouk, I hope, will be different. Already she is beautiful; although she is quite unaware of this. One day she will fall in love. What will happen to us then? Still, I tell myself, there’s time. So far, the only boy in her life is her friend Jean-Loup Rimbault, from whom she is usually inseparable, but who this month has had to go into hospital for another operation. Jean-Loup was born with a heart defect; Anouk doesn’t speak of it, but I can understand her fear. It’s like my own; a shadow that creeps; a certainty that nothing lasts.

She still sometimes talks about Lansquenet. Even though she is happy enough here, Paris seems more like a stopping-place on some as yet untravelled road than a home to which she will always return. Of course, a houseboat is not a house; it lacks the conviction of mortar and stone. And Anouk, with the curious nostalgia that affects the very young, remembers in rosy colours the little

chocolaterie

across from the church, with its striped awning and hand-painted sign. And her eyes are wistful when she speaks of the friends she left behind; of Jeannot Drou and Luc Clairmont, and of streets where no one is afraid to walk at night, and of front doors that are never locked—

I shouldn’t be so anxious, I know. My little Anouk is secretive, but unlike so many of her friends, she still likes her mother’s company. We’re still all right. We still have good times. Just the two of us, tucked up in bed, with Pantoufle a hazy blur at the corner of my eye and the screen of the portable television flickering mystic images against the darkened windows, while Rosette sits out on the deck with Roux, fishing for stars in the silent Seine.

Roux has taken to fatherhood. I really hadn’t expected that. But Rosette – eight years old, and the image of him – seems to have drawn something out of Roux that neither Anouk nor I could have known. In fact, there are times when I think that she belongs more to Roux than to anyone; they have a secret language – of honks and hoots and whistles – in which they can confer for hours, and which no one else shares, not even me.

Otherwise, my little Rosette still doesn’t talk much to anyone, preferring the sign language she learnt as a child, in which she is very proficient. She likes drawing and mathematics; the Sudoku on the back page of

Le Monde

takes her only minutes to complete, and she can add up great lists of numbers without ever having to write them down. We tried sending her to school once, but that didn’t work at all. The schools here are too large and too impersonal to cope with a special case like Rosette. Now, Roux teaches her, and if his curriculum is unusual, with its emphasis on art, bird noises and number games, it seems to make her happy. She has no friends, of course – except for Bam – and sometimes I see her watching the children who pass on their way to school with a look of curious longing. But on the whole, Paris treats us well, for all its anonymity; still, sometimes, on a day like this, like Anouk, like Rosette, I find myself wishing for something more. More than a boat on a river that stinks; more than this cauldron of stale air; more than this forest of towers and spires; or the tiny galley in which I make my chocolates.

More

. Oh, that word. That deceptive word. That eater of lives; that malcontent. That straw that broke the camel’s back, demanding – what, exactly?

I’m very happy with my life. I’m happy with the man I love. I have two wonderful daughters and a job doing what I was meant to do. It’s not much of a living, but it helps pay for the mooring, and Roux takes on building and carpentry work that keeps the four of us afloat. All my friends from Montmartre are here; Alice and Nico; Madame Luzeron; Laurent from the little café; Jean-Louis and Paupaul, the painters. I even have my mother close by, the mother I thought lost for so many years—

What more could I possibly want?

It began in the galley the other day. I was making truffles. In this heat, only truffles are safe; anything else runs the risk of damage, either from refrigeration, or from the heat that gets into everything. Temper the couverture on the slab; heat it gently on the hob; add spices, vanilla and cardamom. Wait for just the right moment, transmuting simple cookery into an act of domestic magic.

What more could I have wanted? Well, maybe a breeze; the tiniest breeze, no more than a kiss in the nape of my neck, where my hair, pinned up in a messy knot, was already stinging with summer sweat—

The tiniest of breezes. What? What possible harm could that do?

And so I called the wind – just a little. A warm and playful little wind that makes cats skittish, and races the clouds.

V’là l’bon vent, v’là l’joli vent

,

V’là l’bon vent, ma mie m’appelle—

It really wasn’t very much; just that little gust of wind and a glamour, like a smile in the air, bringing with it a distant scent of pollen and spices and gingerbread. All I really wanted was to comb the clouds from the summer sky, to bring the scent of other places to my corner of the world.

V’là l’bon vent, v’là l’joli vent—

And all around the Left Bank the sweet wrappers flew like butterflies, and the playful wind tugged at the skirts of a woman crossing the Pont des Arts, a Muslim woman in the

niqab

face-veil, of which there are so many these days, and I caught a glimpse of colours from underneath the long black veil, and just for a moment I thought I saw a shimmy in the scorching air, and the shadows of the wind-blown trees scribbled crazy abstract designs across the dusty water—

V’là l’bon vent, v’là l’joli vent—

The woman glanced down from the bridge at me. I couldn’t see her face; just the eyes, kohl-accented under the

niqab

. For a moment I saw her watching me, and wondered if I knew her somehow. I raised a hand and waved to her. Between us, the Seine, and the rising scent of chocolate from the galley’s open window.

Try me. Taste me

. For a moment I thought she was going to wave back. The dark eyes dropped. She turned away. And then she was gone across the bridge; a faceless woman dressed in black, into the wind of Ramadan.