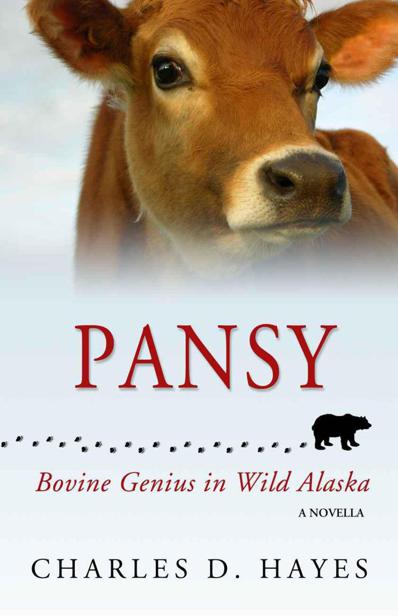

Pansy

Authors: Charles Hayes

Pansy

Pansy: Bovine Genius in Wild Alaska

Charles D. Hayes

Autodidactic Press

Wasilla, Alaska

Copyright © 2012 by Charles D. Hayes

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations and events in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

ISBN

978-0-9621979-9-4

First Edition

Autodidactic Press

P. O. Box 872749

Wasilla, AK 99687

www.autodidactic.com

Contents

He always considered calving in Alaska to be an invitation to disaster, and today was starting out to be no exception. Two inches of wet snow underfoot and, toward the mountains, another April snow squall no doubt headed his way. It would add to his work. He began to mutter, and then stopped in dead silence. There, just ahead in yesterday’s snow, were fresh bear tracks. Jesus, just what I need, a goddamned bear after a cow ready to calf.

Still. No noise, not a sound. He wished otherwise. Couldn’t be that far behind, though. The bear tracks appeared much fresher than the heifer’s, which were almost gone. Maybe he would get there in time to head off another loss. Picking up the pace, he took long strides and unstrapped the .44 pistol holster on his side.

Years ago, a lifetime ago it seemed now, Edward Armstrong had been a state trooper. That’s how he’d met Amy Kellogg. It was a simple traffic stop, and a few days after it happened, she waved him down on the same stretch of highway. Ed likely would have stayed a trooper had not moving to a remote village at one time or another been mandatory. He just couldn’t see it, especially after Mandy was born. He knew other troopers who described how difficult it had been to have their children grow up in a remote village, and he thought it would be too much to ask of a wife and child.

Another few hundred feet, and he came to a draw where he figured the heifer would likely stop to drop the calf. Then he heard it—the chilling primordial cry of an animal in distress. He drew his pistol, keeping his eyes straight ahead, and cocked the hammer without looking at his weapon. He still couldn’t see anything. There it was again—a god-awful bawl, louder this time. Then the wet snow exploded, spewing in all directions, as a brown beast appeared running hell-bent straight for him. Just as he’d rehearsed a thousand times, Ed dropped to one knee, pointed the revolver as far ahead as he could reach with both hands, squeezed the trigger, and fired. The sound awoke the valley, and no creature in hearing distance could tell the first shot from the second or third, and this from a single-action revolver.

As fast as it started, the confrontation was over. Three feet in front of him lay a dying grizzly, a young one at that, not more than his second year on his own. When the bear twitched, Ed pulled the hammer back and fired again, slamming another slug into the back of its head for good measure. Too bad it wasn’t Methuselah, but then, he should have known that because the tracks weren’t nearly big enough. And, of course, if it had been Methuselah, no pistol, not even a .44 at close range would kill him quickly enough to stop him. He was a tough old bastard, no question.

For years now, Ed had been feuding with the monster, an old blond grizzly with a very bad disposition and a strong, insatiable appetite for beef. He hadn’t had a run-in with Methuselah for some time and had begun to think the creature might have died of old age. Bear predation on domestic livestock was unusual in these parts, unless of course you lived where Ed did.

Satisfied that the bruin was dead now, he dreaded what lay in front of him. Good reason to think the worst from the noise, he figured, and he nearly always figured right about these matters. There she was, at the low point of the draw, just where he thought she would be, looking as though she’d already dropped the calf, but he couldn’t see it. The heifer was a goner though. She had a gash in her side, exposing ribs, and her left front leg was snapped it two like a willow twig. As quickly as he could, he raised the Ruger again and fired. She went down without as much as a shiver. He stood in silence watching the crimson artwork in the snow, the blood coming from all sides of her making erratic designs on a canvas of pristine white.

Ed had almost forgotten about the calf when a weak bawl echoed from a short distance ahead in a stand of leafless alders. She looked like an image that would have made the cover of the

Saturday Evening Post

in his grandfather’s day. Trembling and still wet and wobbly from delivery, the calf was the perfect likeness of a Jersey cow.

“My, my, aren’t you something,” he said, gathering up the calf and turning back toward the house in the same motion. “I suppose I couldn’t call you anything but Pansy,” he mused, “that's better than Mutant.” How else would a cow the spitting image of a Jersey come from his beef stock? It made no sense.

The snow was getting heavy, and visibility was quickly fading. He’d walked only a few yards when a heart-stopping image appeared. It was gone so fast, he may have simply imagined it. But, for a moment, he thought he’d seen his nemesis up close. Dreading the worst, he pushed harder through the driving snow.

When he stepped into the house, he carried the calf with him, which was something he had never done before. “Happy Birthday, Mandy,” he said, when his daughter came into the kitchen. She turned seventeen today. “This is Pansy.”

“Original name, Dad,” she said, exiting the room.

The next morning, Ed walked back to the scene of the kill. As he approached, two wolves, a black and a gray, ran up the hill to the west of him. They had no doubt been feeding on the cow carcass. But when he got close to the remains of the cow, there was very little left. Huge bear tracks covered the hard-packed snow. He had been wrong. Methuselah was very much alive and last night had been only a few yards away from Ed and the calf in the blowing snow. It was a chilling thought and one he didn't want to dwell on.

Spring was giving way to summer, bringing warmth and long hours of daylight. Mandy fed Pansy with a bottle, even after the calf had started eating from a pail. Pansy followed Mandy everywhere and at times would bawl incessantly when left alone. Some days it was a bit too much to put up with. Ed thought about getting rid of the calf, and he would have, except that taking care of the animal seemed to be having a positive effect on his daughter. She smiled more often, though she wasn’t very fond of May. Just a year ago this month, breast cancer had taken her mother. Ever since Amy’s death, Mandy and Ed just sort of labored through each day, one grudging motion after another. They had made it an unspoken rule not to talk about Amy, although both wanted to frequently. It was just too soon, too painful.

The thing about running a small farm in Alaska is that most of the folks who try it can’t rid themselves of the notion that it’s the wrong place and the wrong time for such a venture. Alaska is a hard country on people and animals alike. Few farms or ranches in Alaska have many cattle. By Alaska standards, Ed Armstrong, with nearly five hundred head, was a big-time rancher. His 2700-acre spread near Delta Junction was a family homestead from a state-held lottery in 1978, one of a handful in the vicinity with cattle, most of the livestock in Alaska being in the Aleutian Chain or on Kodiak Island. No one in the family, save Ed, Mandy, and Amy, thought raising cattle where they were located was a good idea. Ed had always had serious doubts, although he wasn’t used to saying so out loud. But now he was beginning to daydream about moving away, back to Idaho where he’d grown up.

They were just too far into the wild country. The Kellogg place was too remote. It was Amy who had always talked about how nice it would be to have an actual working ranch on her parents’ dormant property. The land had been left to Amy when her mother, Gladys, and her father, Martin, were killed in a car wreck on the Glenn Highway only a few years after Ed and Amy were married. Thanks to an inheritance from his own parents’ estate, Martin had paid the place off right after winning the right to buy it. Martin had said at the time that the Kellogg clan was wearing thin. Not many left, and now it seemed that his prediction was coming true.

Martin's imprint on the land reflected his ambition. He built two luxurious homes on the ranch, both of the finest logs that could be found. One was the main house, and the other was what he called the guest cottage. When Martin brought people to the ranch in the early days, he always made a comparison to the television show

Bonanza.

He said the Ponderosa ranch house had nothing on him, and he was right. The Kellogg home was beautiful, spacious, and comfortable.

A year after the wreck, Amy couldn’t carry on a conversation for long without talking about how she, Ed, and Mandy could make a go of the Kellogg place as a working cattle ranch. After he quit the troopers, Ed had worked on the North Slope in the oilfield as a captain for a private security firm. His nephew, Randy, worked the place with Amy while Ed was away, until Randy joined the Marines.

Sometimes Ed worked a four-and-two schedule on the Slope, four weeks on and two off. Amy often said that his being away so long was much worse than if he had stayed with the troopers and they’d have had to move to the likes of Barrow, but the money was good. After a decade, he’d saved enough to give it up, or so he thought. He had quit just before Amy was diagnosed with stage-four breast cancer. Fortunately, just as a precaution, he’d kept his medical insurance in play, and it saved him from financial disaster. Amy lived only fourteen months to the day from diagnosis.

These days, Ed sensed it was just his spirit that was broken. What was worse was the realization that all of the time he’d spent working on the Slope had estranged him from his daughter. When she was little, there had been times that they were so close as to seem inseparable, but then, ever so slowly, the distance grew, the more time he was away. Sometimes he hoped it was just his imagination that Mandy seemed to avoid his presence. When he walked into a room, she would exit. Every time he intended to broach the subject with her, though, he could never quite bring himself to utter the first word.

For Mandy’s part, she both admired her father and simultaneously blamed him for her mother’s death, even though down deep she knew he wasn’t responsible. She had become accustomed to brooding alone in her room and often she would eat alone. She would make her father’s dinner and then say she wasn’t hungry. She’d go to her room and lock the door. Her door made a loud noise when it locked, and Ed wondered if that’s why she did it.

Pansy the calf changed all that. After Pansy arrived, Mandy’s mood brightened. Perhaps Mandy thought it was something special, after all, that the calf had been born on her birthday. Still, there was something about that calf and the knowing look in those big black eyes that made it seem to Mandy that Pansy was thinking—thinking about Mandy. One day when Mandy left the barn, she was surprised to find Pansy at the back door bawling as if she were calling her mother. Thinking she must have forgotten to lock the gate with the crossbar, she led Pansy back to the barn only to hear her again at the door a few minutes later, bellowing even louder. She led her to the barn once more, but this time she hid around the corner and watched in awe as Pansy pitched the lock bar up and open with her nose and pranced out of the barn.

“You smart little devil, you,” Mandy said, leading the calf back to the barn. She grabbed a piece of rope and was tying the gate shut just as her cousin walked into the corral.

“Randy, you will never believe what Pansy knows how to do.”

“Probably not,” he said.

“She knows how to open the gate.”

“You sure somebody didn’t just leave it open?”

“That’s what I thought at first, but then I caught her at it.”

Randy laughed. “Well, maybe you should enter her at the fair.”

“Sure, as a gate opener?”

“Well why not? I’m sure you would win because you would be the only entry. Cows just aren’t that smart, you know.”

“Well, this one is.”

“If, you say so.”

“You don’t really believe me, do you?”

“Of course, if you say so, but I don’t think she’ll keep trying to do it.”

With that, he readjusted his ball cap, jumped onto his four-wheeler, and sped off to the pasture. Mandy seemed like a sister to him instead of a cousin. At times she acted many years his junior in maturity, and then, in the blink of an eye, she could seem wise many years beyond her age. “It must be the reading,” he thought. She was seldom without a book in her hand or nearby. He figured it was an escape from grief over her mother’s death, and her aunt’s, both from cancer.