Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (5 page)

Muskrats remain active throughout the year, even when winter closes like a giant vise on pond and marsh. Mostly they remain under the ice, foraging for a variety of foods while using their living quarters and any pushups they may have built as feeding spots. Several muskrats frequently share the same winter quarters, particularly in their domed houses of mud and reeds. Evidently this communal arrangement serves two important purposes: first, it keeps the interior of the house relatively warm; and, second, the warmth helps to keep the water from freezing in the interior entrances to their underwater exits.

Although muskrats normally don’t attempt forays above the ice, they may sally forth if they run short of edibles, as sometimes happens in small wetland areas. Then they’ll leave the water and travel overland, even in the dead of winter, to seek another food source. Also, the need to find a mate may cause lone muskrats to leave their winter quarters in late February or March and set out on a cross-country journey. At such times they may turn up in odd places, such as garages, or may be killed while crossing highways.

Heidi, our black Labrador retriever, and I once had a painful adventure with one of these winter wanderers. I happened to glance idly out the window one afternoon when the snow lay deep on the field adjoining the house. A distant movement caught my eye, and I spied a brown object moving in our direction. As it drew closer, the object soon resolved itself into a muskrat.

Intrigued by such an incongruous sight, I took Heidi and went outdoors for a closer look. The muskrat continued to move steadily in our direction until it was perhaps twenty feet away. Then, without warning, it accelerated and charged straight at us at top speed.

Astounded by this turn of events, I failed to react in time. Heidi, curious about this strange creature, lowered her head, and the onrushing muskrat bit the unfortunate dog savagely on the end of the nose! Blood, which always looks far worse on snow, seemed to fly everywhere, while the muskrat turned and fled in the direction it had come from. Because I had to attend to Heidi’s wounded nose, we never did learn what became of the muskrat.

What was a muskrat doing at that time of year, exposing itself to danger in open, snow-covered fields? There was no rabies in Vermont at the time, so any suspicion of a rabid animal can be eliminated. No doubt the peripatetic muskrat had either been forced to seek a new food supply or was heeding the siren call of the mating season. At any rate, it provided a thoroughly memorable experience, albeit a most unpleasant one for the unhappy Heidi!

As befits their semiaquatic status, muskrats have a full complement of adaptations to equip them for life in the water. Like beavers, muskrats are notable divers without benefit of outsized lungs. With the same sort of adaptations possessed by beavers, they can easily spend ten minutes underwater, and longer dives of up to fifteen minutes are by no means unknown. One biologist saw a muskrat dive and remain submerged for an astounding seventeen minutes, come to the surface for just three seconds, and then dive for another ten minutes!

The muskrat has other useful adaptations as well. Its hind feet are partially webbed to provide efficient paddles for easy movement in the water, while its long tail acts as a rudder. On occasion, this tail can present a rather comical appearance: when the muskrat is floating at rest, it sometimes angles its tail upward, completely out of water. There, unsupported, it forms a shallow curve, first upward and then, farther back, gradually drooping toward the surface.

Meanwhile, the muskrat’s admirable fur coat protects its owner against the effects of even the most frigid water. Although muskrat fur isn’t quite as highly prized as that of the beaver, it’s nonetheless very handsome. Beneath the long, dark brown, glossy outer guard hairs lies a dense coat of fine, soft, grayish underfur, designed to keep water away from the muskrat’s skin.

Because of the high quality of their pelts, muskrats have long been a staple of the fur trade in North America. In Wisconsin, for example, the value of muskrat pelts from 1970 to 1981 exceeded $33 million. Despite being both extensively and intensively trapped each year, however, the muskrat has remained abundant down through the years and continues to thrive. This is due to a combination of the muskrat’s adaptability and its exceptional reproductive capacity, which is far more like that of the vole than the beaver.

For an animal of its size—two to four pounds—the muskrat has a remarkably short gestation period, lasting a little less than a month. Further, it has at least two litters annually, often three, and sometimes as many as four, with most litters consisting of four to eight young. Add the fact that a female muskrat can breed as early as eight months, and the biological potential of a pair of muskrats, if completely unchecked, is astronomical!

Obviously, many influences restrain the growth of muskrat populations: otherwise we’d be knee-deep in muskrats. Disease, parasites, injuries, and predators all take a toll. Humans are now a major predator of muskrats, but mink are also an important natural enemy. Thoroughly at home in the water, mink often enter muskrat houses in search of a meal. There, despite being much smaller than an adult muskrat, these fierce little predators quickly do away with the occupants and dine in style. Otters, too, even swifter and more at home in the water than mink, sometimes prey on muskrats.

Other predators also abound, though they mostly prey on young muskrats. Big snapping turtles and large fish, such as northern pike and garfish, relish young muskrats and feed on them at every opportunity. Raccoons, hawks, great horned owls, and alligators also esteem muskrats as food. All in all, this system of muskrat fecundity and numerous predators seems to work very well, as muskrats are neither scarce nor overabundant in most locations.

If there’s any threat to the muskrat, it’s habitat loss. Despite its adaptability, the little marsh dweller can’t survive without suitable areas for food and shelter. Habitat loss comes from two sources. The first is the continued drainage of wetlands for everything from agricultural land to development. Although laws protecting wetlands have helped to slow the destruction of our enormously important wetlands, they haven’t yet halted it.

The second major source of habitat loss for muskrats comes from the nutria, or coypu

(Myocastor coypus),

a rather large rodent that weighs fifteen to twenty pounds. It was unwisely imported from South America for its fur, and its introduction has had serious repercussions for both marsh and marsh dwellers. The nutria is found mostly in coastal areas in Maryland and Delaware, from Georgia to Louisiana and Texas, and in parts of California, Washington, and Oregon. Inland, there are also some infested areas in parts of the Midwest.

The problems with this interloper are twofold: first, the muskrat can’t compete with the nutria for food; and, second, the nutria’s feeding habits simply destroy a marsh. Where muskrats eat the stems and leaves of aquatic plants, as well as some tubers and fleshy roots, the nutria totally destroys the root systems of these plants. Once the vegetation is eliminated, there’s nothing to hold the land in place, and the marsh is washed away.

Louisiana, where coastal wetlands have enormous economic value not only for muskrats, but also for alligators, shrimp, and waterfowl, is losing 300,000 acres of these priceless wetlands annually to nutria “eat-outs.” The state is fighting back, however: in addition to promoting the use of nutria fur in an effort to control these destructive pests, Louisiana is also trying to develop a market for nutria meat. And in Delaware, the state has recently received a $2-million federal grant to eradicate the nutria, if possible.

Despite the habitat destruction wrought by humans and nutria, an enormous amount of suitable habitat remains in North America for the versatile muskrat. Considering its enormous reproductive potential, and the vast acreage of available habitat, it seems likely that this fur-bearing rodent will continue to be a common sight throughout most of North America.

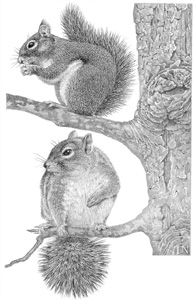

Red squired; gray squirrel

3

A Sylvan Odd Couple: The Red Squírrel and the Gray

MYTHS

Red squirrels drive out gray squirrels.

Red squirrels drive out gray squirrels.

Red squirrels castrate gray squirrels.

Red squirrels castrate gray squirrels.

Gray squirrels remember where they bury nuts.

Gray squirrels remember where they bury nuts.

Squirrels are vegetarians.

Squirrels are vegetarians.

Gray squirrels are very tame.

Gray squirrels are very tame.

THE RED SQUIRREL

(TAMIASCIURUS HUDSONICUS)

AND THE EASTERN GRAY SQUIRREL

(SCIURUS CAROLINENSIS)

ARE BOTH TREE SQUIRRELS AND LIVE IN PROXIMITY TO EACH OTHER THROUGHOUT A WIDE STRETCH OF TERRITORY, YET THEY DIFFER WIDELY IN SIZE, MODE OF LIVING, FOOD AND HABITAT REQUIREMENTS, AND MOST ESPECIALLY IN PERSONALITY.

These two tree-dependent rodents inhabit the same tracts of forest land from the southern edge of the eastern Canadian provinces down the Atlantic coast to Virginia, west to Illinois, and back north through parts of the Dakotas; narrow bands also extend southward into Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. All or parts of some five Canadian provinces and twenty-four of the lower forty-eight states harbor both red and gray squirrels.

Within this broad area, two of the most common and enduring of all wildlife myths have sprung up. It’s an article of faith with many people that “the reds drive out the grays,” and, even worse, that the reds castrate the male grays.

While it’s true that red squirrels sometimes chase their big relatives, they hardly do it with the intention of “driving them out” in the sense of excluding them from a large area. Far more than gray squirrels, reds are highly territorial in regard to their dens and caches of food. Thus, if a gray squirrel approaches one of these too closely, the red may chase it for a short distance. Once the gray vacates the small area around den or cache, however, the red has no further interest in pursuing it.

This behavior is similar to what is often seen in birds. It’s a common and entertaining sight to see small songbirds chasing and harassing much bigger birds, such as crows, that have violated the airspace above the songbirds’ nests; this behavior even extends to attacks on hawks and other birds of prey that fly too close to a nest site. In both cases—squirrels and birds—the aggrieved party seems to have the upper hand, and the offending party flees. In the same manner, gray squirrels will drive away reds that come too close to their dens.

Many people say they’ve seen red squirrels chase grays away from backyard bird and squirrel feeders. No doubt they have, in some cases, but this behavior is far from universal. In years of watching the interaction of the two species at our feeders, only twice have we seen a red squirrel take after a gray.

In one instance the gray ran up a tree, pursued by the red. When the red got too close, the gray turned on it, and the red squirrel fled down the tree. A moment later the red made another try; this time it took only a menacing move of the gray squirrel’s head to make the red hurriedly depart for good. In another incident, we watched a red run toward a gray eating fallen seeds beneath a feeder. The gray ran a short distance, although not in much haste; the red pursued for three or four feet and then turned back to feed, clearly uninterested in chasing the gray any farther.

In contrast to these two incidents, we’ve observed countless occasions when grays have pushed reds out of our feeders or chased them away from a choice spot under a feeder. In general, we’ve seen the reds defer to the much bigger grays in numerous ways that make it abundantly clear that reds don’t “drive out the grays.”

It’s also likely that if a hungry red squirrel approaches a gray squirrel satiated from stuffing itself with sunflower seeds, the gray may allow itself to be chased out of a feeder. At that point the red squirrel is powerfully motivated by hunger, while the gray has no incentive to remain or to act aggressive.

All of these observations and suppositions aside, there is irrefutable proof that red squirrels don’t drive out the grays. If they did, as one biologist pointed out, there would be few if any gray squirrels left in the very large areas where the ranges of the two species overlap. Obviously this has not happened. Both species are common throughout most of these areas, and go their separate ways with only occasional minor conflicts.

Because red squirrels do chase grays on occasion, the erroneous conclusion that the reds drive out the grays is at least partially understandable. However, the myth that the reds castrate the male grays must have originated either as the result of an overheated imagination or as a deliberate tall tale.

Merely consider the facts. The gray squirrel generally weighs from two to three times as much as the little red. Even what are normally the most peaceable of animals will fight savagely, if necessary, to protect themselves. Nor could a red squirrel, with its little teeth, neatly snip off the testicles of the gray with one or two bites. The notion that the much bigger gray squirrel would allow its testicles to be gnawed off by its little relative is preposterous; long before that happened, the gray would make squirrel hash of the offending red!

The final proof, if any is needed, is the same as for the myth that red squirrels drive out the grays. If the reds were successfully sterilizing the grays, there would soon be few grays within the red squirrel’s range—and that clearly isn’t the case.

Grays are not only much longer and heavier than the little reds, but their size is exaggerated by their long, bushy tail. This plume like affair can be quite splendid on a healthy specimen, partially because the gray’s tail is longer in proportion to head and body than the red’s tail. When a gray is sitting up, its beautiful tail follows the line of its back as far as the head and then curves backward in a graceful arc. This characteristic elicited Winifred Welles’s perceptive imagery in

Silver for Midas:

My squirrel with his tail curved up

Like half a silver lyre.

Both species shed their coats twice a year and simultaneously grow new ones, first in late spring and again in early autumn. As in the case of birds, this process is known as molting. Oddly enough, the tail in both species molts only once, in the middle of summer.

Considering how often these two squirrels can be found in the same sections of woodland, it’s worthwhile—and quite fascinating—to see how different their lives are in many respects. Food requirements and feeding habits are as good a place as any to start.

In simplest terms, gray squirrels depend on nuts as their most essential food supply; historically, wherever nuts—acorns, hickories, beechnuts, butternuts, and black walnuts—are abundant, so are gray squirrels. Red squirrels, on the other hand, rely heavily on the seeds and buds of coniferous trees: pine, spruce, fir, and hemlock. Thus, even though they relish nuts where available, their range is confined mostly to coniferous or mixed-growth forests. In a nutshell (pun intended), that is the most important difference in the food requirements of the two species.

Of course, nature is never quite that simple, so there are many complexities and permutations of the simple formula that nuts equal gray squirrels, while cones equal reds. Red squirrels eagerly devour nuts when they’re available and can subsist on them in the absence of seeds from cones. The converse isn’t true, however; gray squirrels don’t feed on the seeds from cones, and so are dependent on nuts. In addition, a wide range of foods is shared by the two species. Fungi, fruit, many kinds of seeds, hardwood buds, sap, and the inner bark of trees all are part of the diets of both reds and grays.

Both species also share another food source, one that isn’t commonly thought of in connection with squirrels. Far from being vegetarians, as most people believe, reds and grays alike are quick to consume birds’ eggs and baby birds whenever they have the chance, and grays are known to feed on forest-dwelling frogs. The reds, even more omnivorous than the grays, go a step further and often eat the young of small mammals such as mice and voles.

Just as the basic food requirements for the two species are widely divergent, so too are their methods of caching food and consuming it. Gray squirrels are justly noted for industriously storing nuts underground. These are buried singly in dispersed fashion throughout each squirrel’s territory.

This behavior has led to the common myth that gray squirrels remember where they’ve buried each nut. Research has shown that grays don’t have that kind of remarkable memory; although they may recall general areas where they’ve buried nuts, the location of individual nuts isn’t part of their memory bank.

That being the case, how do squirrels find the nuts when they need food? The answer lies in their remarkable sense of smell. Gray squirrels locate buried nuts—even under many inches of snow—by scent alone! This means that individual squirrels dig up nuts buried by other squirrels wherever they happen to smell them. Such behavior, though it might seem a bit unjust, probably results in something like a fair exchange in most cases.

This uncertain and somewhat haphazard retrieval of buried nuts has one vital, if unintended, result. Many nuts are never found, and these sprout and grow into new nut trees. While some nuts, such as the acorns of white oaks, will sprout on the surface of the ground, others must be buried in order to germinate.