Overlord (Pan Military Classics) (14 page)

Read Overlord (Pan Military Classics) Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Some subordinate German commanders, such as General Richter of 716th Division, responded more forcefully to the spectacle of enemy paratroopers dropping around them. Richter directed a battalion of infantry with an anti-tank gun and self-propelled artillery support towards Bénouville to recapture the Orne and Caen Canal bridges in the early hours of the morning. But when their leading light tank was knocked out by a British PIAT and the paratroopers opened heavy fire on the counter-attacking force, the Germans contented themselves with occupying Bénouville and exchanging fire with the British. 716th Division’s operations were conducted with nothing like the determination that could have been expected from a top-class formation.

‘You could see that the Germans were really frightened because they started being so nasty,’ said Nicole Ferté,

8

one of the local inhabitants of Hérouville, three miles south of the Orne bridge. ‘They had always been so courteous in the past.’ Madémoiselle Ferté, the 20-year-old daughter of a local garage owner, had lain on the floor during the bombing, sheltering her eight-year-old sister and listening spellbound to the sound of the glider tugs and transport aircraft overhead before midnight. Suddenly there was a knock at their door, and the local teacher stood outside. A wounded British soldier was in the school. Could Nicole come and interpret? Together they hurried back down the road and, in a mixture of half-remembered English, French, and even German, began to talk to the airborne soldier, lying in great pain with a broken leg. They had just given him tea when German soldiers burst in. The civilians were busquely sent to their homes, the British soldier taken away. Most of the local inhabitants hastily fled from the village, but the Fertés stayed through a week when the fighting raged to within a few hundred yards of their door,

‘because we were certain that liberation must come at any moment. The only other people who stayed were the girls who had been sleeping with Germans.’ After a week, the Germans abruptly ordered all the remaining occupants to leave Hérouville, and they endured many weeks of fear and privation before they saw the village again.

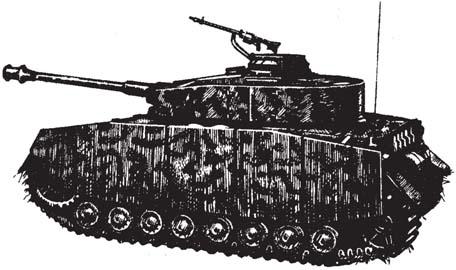

At 21st Panzer’s headquarters, although two companies of infantry exercising north of Caen reported the British glider landings immediately, in the absence of General Feuchtinger and his senior staff officer the only action that could be taken was the immediate removal of divisional headquarters to its operational location. Corporal Werner Kortenhaus, wireless operator in one of the division’s 127 Mk IV tanks, was out on picket with two other men when they heard the massive air activity overhead – the sound of aircraft descending, and then climbing once more as the glider tugs loosed their tows. As the panzer crew approached their platoon harbour in the darkness, they could see the shadows of men already clambering over the tanks, preparing to move off. While his own crew hastily unloaded their drill rounds and filled the turret with armour-piercing ammunition, Kortenhaus ran to the house of the Frenchwoman who did their laundry to collect their clean clothes. By 2.00 a.m., the crews were in the tanks and ready to move. Yet it was 8.00 a.m. before the 1st Tank Battalion under Captain von Gottberg began to roll north from its harbour up the long, straight road north to Caen. The 2nd Battalion under Major Vierzig did not start to move until 9.00 a.m., although that officer had held his tanks on standby since 2.20 a.m. No order had been given to them and for this failure responsibility must be shared between Speidel and Feuchtinger, who at the very least displayed an astounding lack of initiative when he arrived at his headquarters some time between 6.00 and 7.00 a.m.

Lieutenant Rudolf Schaaf, commanding a self-propelled battery of the 1716th Artillery, was telephoned at 3.00 a.m. and ordered to

take his guns to join the counter-attack against the British airborne bridgehead. Yet he had driven only a few miles across country when he received a radio message recalling them to their original positions. It was clear by dawn that the seaborne menace would have to be met by every infantryman and gun that the defenders possessed.

Shortly before H-Hour, Allied bombers struck the station at Caen and soon afterwards fighter-bombers began to strafe German installations and barracks. A loudspeaker vehicle toured the streets, ordering civilians to stay in their houses. Throughout the day there were intermittent Allied air attacks. By mid-morning the first truckloads of British prisoners were being driven through the streets. The first of more than 80 ruthless executions of French civilians alleged to have assisted the invaders were taking place at the barracks. Early reports of the airborne landings and the fleet offshore were as confused as those reaching German headquarters. The overwhelming sensation among the French was terror that a landing might fail. The memory of Dieppe, the possibility that all the suffering, destruction and death might be in vain, hung heavy over Caen and all Normandy that morning and through the days that followed. A local historian described the events of the dawn of D-Day: ‘Thus Caen, like other towns in Normandy, passed the night of 6–7 June in fire and blood, while elsewhere in France they celebrated the invasion by drinking champagne and dancing to the gramophone.’

9

Before dawn, the invasion coast was lit by flares and flashes as the naval guns pounded the defences, explosions of every hue rippling up and down the shoreline as hundreds of launches and landing craft scuttled amid the dim silhouettes of the battleships and cruisers, transports and rocket ships a few miles out to sea. No

man who saw it ever forgot either the spectacle of the vast invasion fleet crowding the Channel at first light on the morning of D-Day, or the roar of the guns rolling across the sea, or the tearing rasp of the rocket batteries firing over the heads of the men in the landing craft. Nine battleships, 23 cruisers, 104 destroyers and 71 corvettes dominated the 6,483-strong assembly of converted liners, merchantmen and tank landing craft now shaking out into their positions a few miles offshore. 4,000 landing ships – craft and barges of all sizes – would carry the troops ashore. Alongside the transports, overburdened men clambered clumsily down the scrambling nets into the pitching assault craft below. For many, this was among the most alarming experiences of the day. Thousands of men tossing upon the swell strained to make their eyes focus through binoculars upon the coastline ahead. Captain Hendrie Bruce of the Royal Artillery wrote in his notebook: ‘The villages of La Breche and Lion-sur-Mer are smothered with bursts, and enormous dirty clouds of smoke and brick dust rise from the target area and drift out to sea, completely obscuring our target for a time and enveloping many craft in a veritable “fog of war”.’

10

Gunnery observation was to be one of the least satisfactory aspects of the landings, with scores of ships compelled to waste ammunition on harassing objectives selected from the map, for lack of targets pinpointed by forward observers. As the first waves of landing craft headed for the shore, the guns lifted their barrage precisely according to the time schedule. As a result, with so many craft running minutes late, the German defences enjoyed a precious pause before the first infantry hit the beaches.

Probably the first Allied vessel to be destroyed by the shore batteries was PC 1261, one of the American patrol craft leading landing craft towards Utah beach. Lieutenant Halsey Barrett was concentrating intently upon the task of holding a course of 236 degrees true when the quartermaster stepped down into the

chartroom and reported that the batteries ashore had just straddled the craft. Seconds later, just 58 minutes before H-Hour at 5.34 a.m., they were hit.

There was a crash – not terribly loud – a lunge – a crash of glass, a rumble of gear falling around the decks – an immediate, yes immediate, 50° list to starboard – all lights darkened and the dawn’s early light coming through the pilot house door which had been blown open. The Executive Officer immediately said: ‘That’s it’, with finality and threw down his chart pencil. I felt blood covering my face and a gash over my left eye around the eyebrow.

11

While most of the crew took to the liferafts as the craft turned turtle, Barrett and a cluster of others clung to the upturned hull, watching the great procession of landing craft driving on past them towards the shore.

A landing craft LCVP with thirty or so men aboard was blown a hundred feet in the air in pieces. Shore batteries flashed, splashes appeared sporadically around the bay. Planes were flying in reasonable formation over the beach. One transpired into a huge streaming flame and no trace of the plane remained. Aft of us an LCT lay belly skyward no trace of survivors around it. The USS battleship

Nevada

a mile off to the northwest of us was using her 14-inch guns rapidly and with huge gushes of black smoke and flame extending yards and yards from her broadside . . . There was a beautiful sunrise commencing . . . A small British ML picked up with difficulty one of our men shrieking for help while hanging on a marker buoy. His childish yells for help despite his life jacket and secure buoy was the only disgraceful and unmanly incident which I saw . . .

12

Most men, even those who had suffered as savage a shock as the crew of PC 1261, felt reassured by the sense of the Allied armada’s dominance of the sea. Barrett and the other survivors knew that

somebody would pick them up as soon as they had time to spare, as indeed they did. For the men of the British and American navies, there was an overwhelming sense of relief that they faced no sudden, devastating attack from the Luftwaffe as some, despite all the reassurance of the intelligence reports, had feared they might. ‘We were all more or less expecting bombs, shells, blood etc.’ wrote a British sailor on the corvette

Gentian

. ‘Dive bombers were expected to be attacking continually, backed by high-level bombing. But no, nothing like that . . . Instead, a calm, peaceful scene . . . The Luftwaffe is obviously smashed.’

13

In England early that morning, only a few thousand people knew with certainty what was happening across the Channel, and only some thousands more guessed.

The Times

news pages were dominated by the latest reports from Italy, with the Fifth Army past Rome; there was a mention of Allied bombing of Calais and Boulogne. The daily weather bulletin recorded dull conditions in the Channel on 5 June, with a south-west wind becoming very strong in the middle of the day: ‘Towards dusk the wind had dropped a little, and the sea was less choppy. The outlook was a little more favourable at nightfall.’

Outside Portsmouth, at 21st Army Group headquarters, Montgomery’s Chief of Staff, Major-General Francis de Guingand, turned to Brigadier Bill Williams and recalled the beginning of other, desert battles. ‘My God, I wish we had 9th Australian Division with us this morning, don’t you?’ he said wryly.

14

Some of the British officers at SHAEF were taken aback to discover their American counterparts reporting for duty that morning wearing helmets and sidearms, an earnest of their identification with the men across the water. Brooke described in his diary how he walked in the sunshine of St James’s Park: ‘A most unreal day during which I felt as if I were in a trance entirely detached from the war.’

15

In his foxhole in the Cotentin, Private Richardson of the 82nd Airborne was woken by daylight, and the overhead roar of an Allied fighter-bomber. Hungry and thirsty, he munched a chocolate bar until the word came to move out. Richardson picked up a stray bazooka without enthusiasm, because he had only the barest idea of how to use it. Among a long file of men, all of them unknown to him, he began to march across the Norman fields, ignorant of where they were going. They reached a hedge by a road and halted, while at the front of the column two officers pored over a map and discussed which way to go. Suddenly everybody was signalled to lie flat. A car was approaching. They lay frozen as it approached. Richardson and the others could see the heads of its three German occupants passing the top of the ledge like targets in a shooting gallery. It seemed that no one would move against them, each American privately expecting another to be the first to act. Then one man stood up and emptied a burst of Browning automatic rifle fire at the car. It swerved off the road into a ditch, where somebody shouted, ‘Finish ’em!’ and tossed a grenade. But the Germans were already dead. One of them was Lieutenant-General Wilhelm Falley, commanding the German 91st Division, on his way back to his headquarters from the ill-fated war games in Rennes.

Like Richardson, many of the paratroopers had never seen a man killed before, least of all on a peaceful summer morning in the midst of the countryside. They found the experience rather shocking. Leaving the Germans where they had fallen, they marched on through the meadows and wild flowers, disturbed by nothing more intrusive than the buzzing insects. They encountered another group from the 508th, presiding over 30 German prisoners, arranged in ranks by the roadside as if for a parade. Most were Poles or oriental Russians. One American threw a scene about shooting them: ‘The Japs killed my brother!’ He was dissuaded at the time, but Richardson heard later that the whole group had been killed.