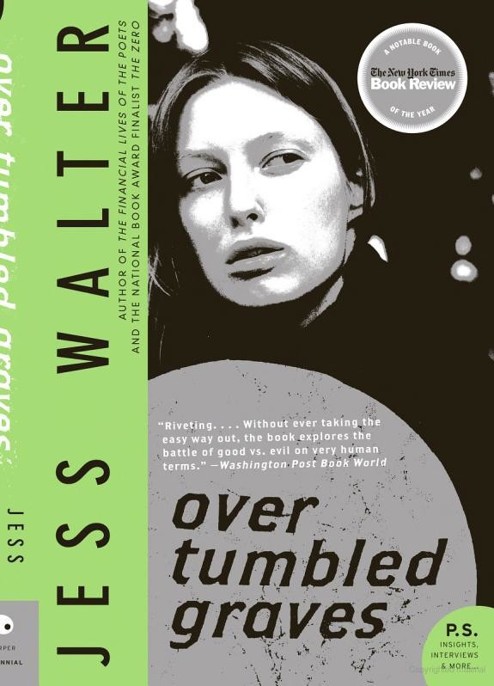

Over Tumbled Graves

In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing Over the tumbled graves.

—T. S. E

LIOT

,

The Waste Land

April: Burial of the Dead

Caroline Mabry was transfixed by falling water. For her, the…

Riverfront Park covered a hundred acres surrounding Spokane Falls, spread…

“You know what awful means?” Dupree squinted into the sun.

Caroline had gone back to the office, turned off her…

After witnessing a couple of them firsthand, Alan Dupree had…

Lenny was sitting in his uncle’s car across the street…

“That’s him.”

Thick Jay was in his underwear and a once-white T-shirt,…

Dupree’s first thought when he was called to the river…

Caroline expected more from death. Whether it came from some…

May: A Game of Chess

The chair she sat in was a throne of leather…

Figure 450,000 people in the greater Spokane area—counting from the…

She couldn’t be twenty, even though that’s what she claimed.

On his way to the hospital Dupree tapped his cell…

The headlights would be the first thing, and every time…

By 10 P.M., the picture Dupree had in his mind…

The alley opened into the parking lot and back entrance…

The tires bounded once off the curb and then Dupree…

The thin, exhausted girl, who had decided to change her…

They sat in Dupree’s car, in front of Caroline’s house.

June: The Fire Sermon

Supplemental Report

When she was little, Caroline called the sunrise “Mr. Pink…

The girl goalie was coming right at Marc Dupree. He…

Burgundy Street stunk. Not like Bourbon, of course, which ran…

It wasn’t long after the drunk girls joined their table…

Bourbon after midnight was a thin but enthusiastic stream of…

Date: 6 June, 0800 hours

“Okay, now apply the models of pre- and post-offense behavior…

Lenny Ryan’s beard was coming in nicely. He turned from…

July: Death by Water

As always, the first sign was the disappearance of the…

To her surprise, Caroline found that she rather liked working…

Dupree bent down, shined his flashlight beneath the tree limbs,…

Caroline was flipping through the channels when she saw footage…

Dupree lurched awake in his car, in front of his…

Shaking, Caroline backed into her house, grabbed her cell phone…

Lenny Ryan found himself thinking about the dog he’d had…

Her first thought was to turn herself in, call Internal…

The recipe called for golden mushroom soup, but all she…

The drug counselor’s thick face spread into a smile. “I’m…

August: What the Thunder Said

A jogger found the fifth body in a blind of…

The calf had fallen into what Angela called a coulee,…

At 6 P.M., halfway into his second-to-last shift as a…

“Please, get up,” Caroline said, looking down the long hall…

There was a pinch, and then Rae-Lynn felt a warmth…

Kevin Verloc’s shoulders were carved and sculpted, and he had…

So fucking cold. She whispered, “Kelly, you took all the…

Spivey stood a few feet away, chewing on a poppy-seed…

The backyard extended forty feet behind Kevin Verloc’s house before…

The doubts ran through her mind faster than she could…

Burial of the Dead

Caroline Mabry was transfixed by falling water. For her, the river had other currents, pulling her to its banks when she was upset or distracted, when she wanted to lose herself. She did this most often at the falls—the dramatic series of rocky, churning rapids at the center of her city. Determined upstream, even languid and eddied in places, the Spokane River began to tumble here, to froth and roil, and eventually to fall.

Sometimes the river’s pull surprised Caroline. She would be running errands or jogging or riding her bike and suddenly find herself here, on the footbridge between the upper falls and the Monroe Street Dam. She was amazed by this place, by what it meant for a city to have at its heart a tumbling, roaring waterfall. Here, overwhelmed by scale, she could drift into epiphanies of scope and flow and believe that a river has a purpose more vital than transportation or power. The river cleansed the city, carried away its debris, its sump and its suicides. The river irrigated the long, gray wound of civilization. Over time she’d begun to bring her own chronic infections to the river, her random loneliness and cyclic despair, her isolation. And if she wasn’t cured by the falls, her jagged anxieties were

at least dispersed, drowned out by white water, dwarfed by boulders that jutted like broken bones from the river’s skin.

Caroline paused on a footbridge over the falls, checked her watch, and finished crossing, pushing the baby stroller deeper into the park, over an embankment covered with people and blankets, Frisbees and Hacky Sacks, to a still arm of the river, dammed off from the rocky channel across the park as a place for ducks and park benches, for lovers and quiet contemplation. The Spokane River was steel and steady here, gray, moving like molten metal between its banks. Caroline wondered what it meant to be more comfortable with the airy roar of the falls than with this pleasant meandering, this stillness. But she blinked away her doubts and concentrated, wheeling her stroller along the sidewalk, finding her place. Waiting.

At thirty-six, Caroline Mabry looked ten years younger and felt ten years older, with round green eyes and short brown hair that softened her tall, athletic build. She stood next to the stroller at the base of a wide footbridge and leaned against a piling to tie her new running shoes. Looking up, she made eye contact across the bridge with a transient who had been in the park all day, a transient in new running shoes. Then, as if operating from a checklist, Caroline stretched, bent at the waist in her nylon running suit, pushed away from the piling, checked on her baby, put on her sunglasses, and surveyed the park.

The park that day had a strange but familiar feel, very much like a map on a wall, with pins marking the major players. But it was also tinged with a fleeting déjà vu, a sensation Caroline had always imagined was akin to losing one’s mind, attaching meaning to every movement. Looking around the park, she allowed herself to believe that

none of it

was real—not the Frisbees, not the dogs, not even the river, and certainly not herself, a young mother out for a walk on a sunny day in the park.

Across the bridge, a businessman on a park bench paused to look up from his two-day-old

Wall Street Journal

, caught her eye, and smiled. Her own thoughts seemed deafening, as if everyone would know what she was thinking, and wonder how she knew the businessman had been there all day and that he was wearing the same brand of ninety-dollar running shoes as the transient, the same as she was.

The three—Caroline with her baby, the transient with his pack, the businessman with his newspaper—made a sort of triangle around the wide footbridge, Caroline on one side, the other two across the bridge. In the middle of the triangle, just over the bridge on the side of the businessman and the transient, was a sinewy black kid in baggy carpenter pants, a white T-shirt, untied cross-trainers, and a New York Giants football cap. His name was Kevin Hatch, but he went by the street name Burn, a fact that Caroline knew as well. If someone did share her thoughts, that person would be amazed at the things she knew, the nearsighted omniscience she had in the park that day, like a god who knows everything except what will happen next.

A voice crackled in Caroline’s ear:

“We’re good. Go on the next buy.”

Caroline sat down against a bridge piling with a paperback book and turned the page every minute or so. After five pages, she stood and checked her baby, then sat back down and turned more pages. Within ten minutes, a man had approached Burn, a man about forty, with shoulder-length hair, wearing khaki pants and a plain black T-shirt. He wore sunglasses, and Caroline was taken by the fact that she knew nothing about him. She watched Burn greet the man, first suspiciously, then warmly, as if the man had mentioned a mutual acquaintance to gain Burn’s confidence. The man spoke and Burn listened, nodding a couple of times.

Nearby, conversations rose and blended—a couple’s charmed declarations, teenage pleas, some hushed conspiracy from men in suits. On the other side of the bridge, the transient eased up from the ground and began moving forward as the sun edged away from thin cloud cover, lighting the park and river as if a curtain were being drawn.

They waited for Burn to reach out with a cupped hand to the man in khaki pants, a move repeated dozens of times each day—drugs going out in one handshake, cash coming back in the next. But it didn’t happen. They just talked, the man in khaki doing most of the talking, Burn adding a word here or there. Still, they watched, waiting for the deal. Finally, Burn put his hand in his pocket. Thirty feet away, the businessman folded up his old newspaper, stood, and reached into his jacket.

Caroline stood too, ready, but she was stopped by the nearby jan

gle of a cell phone, familiar but muffled. Had she left her phone on? It was in the stroller. She paused, looked around, then bent forward to turn the phone off. She wedged her hand beneath the bundle and grabbed the phone, but snagged the blanket too. She stood quickly and the blanket—tucked under the baby into the side of the stroller—went taut, like a slingshot. Or a rebounding trampoline.

It was an image she would have to compose later, because in that moment Caroline lost track of the sequence and sense of things. Disparate images crashed together, straining against the time required to process each event.

People screamed. The baby was launched into the air. A man reached out, but too late. The baby flew over the railing. People began rushing toward the bridge, to watch or to help, perhaps only sorting out their own motives later. The baby hit the water, barely breaking the surface, floating on its back in its swaddling blanket, pulled along by the slow gray mass as it eased through the downtown park. Like Moses.

Startled by the screaming, the drug dealer Burn and his potential customer in khaki pants looked up from their conversation in time to see two undercover cops, dressed as a transient and a businessman, handguns drawn, coming toward them, but momentarily caught up in the crowd coming toward the bridge to help the baby, or to watch it drown.

Caroline saw all of this from the other side of the river, frozen in place next to her stroller, and before she could form a full sentence—“No! It’s just—” a man in jeans and a sweatshirt had leaped over the footbridge and into the water.

“—a doll!” Caroline finished. As if for punctuation, her cell phone rang again.

“Suspects on the move!”

someone yelled over the radio.

Caroline turned away from the river. Both men were coming toward her, the two detectives fifteen feet back and falling away in a crowd of gawkers. She reached behind her back for her gun, but there was too much commotion over the bundled doll floating downstream—people pulling at Caroline’s arms, pointing, trying to comfort her. Burn and the other man raced by, and she could only grab at their shirts. She managed to get a hand on the older man in khaki, but he swung wildly and hit her in the neck. She fell away.

Sergeant Lane, still dressed as a businessman, was there immediately, crouching to see if she was okay.

“I’m fine.” Caroline rubbed her neck and nodded in the direction the two suspects had gone, and Sergeant Lane ran after them, much to her relief. There was a ringing then, and Caroline realized the phone was still in her hand. She stared at it. Dumbfounded, she stood, brushed herself off, pressed the button, and held the phone to her ear.

“Hello.”

“Hey, babe.”

Joel.

“How’d the bust go?”

She turned the phone off.

Two other drug detectives came from the van, but they were too late and were coming from the wrong direction. Caroline couldn’t watch the thing unravel anymore and so she turned back to the water. In the calm stretch of river, the hero had reached the doll Caroline was planning to give to her niece, but he could do nothing except swim with it to shore and hold it up by a plastic arm. The people on the bridge applauded anyway and he shrugged, embarrassed.

As Caroline stood along the river, she thought she knew how the man must feel, crawling from the dark water. Was he still a hero, even if the baby wasn’t real? For herself the question seemed even more pointed: If the trappings weren’t real—the baby, the stroller, the jogging suit—then what about the feelings? The disconnection and the longing for something more. Were those things real?