Out of Darkness (32 page)

Authors: Ashley Hope Pérez

But something had to stay behind. For the next two days, Naomi's body moved through her daily routine. Whole hours disappeared uncounted, unlived. School. Washing and hanging and folding. Serving meals and clearing them away. Sweeping, mopping, dusting. The house was cleaned but not lived in, not by Naomi.

It was a way of surviving, and it was a preview of what her life would be if their plan failed.

Â

NAOMI

Naomi pulled open the door to the cafeteria cleaning supply closet with no more thought than she'd given to any other task over the last two days. She was vaguely aware that she was here to get a box of baking soda for the home economics teacher. She did not expect to find children sitting in a circle on the floor, holding hands. She did not expect to see a ring of candles with her mother's braid and red dancing shoes at the center.

Her eyes adjusted, and she recognized faces. Cari, Beto, and Tommie's cousin Katie. Their eyes were wide and surprised.

“Cari! Beto! What is this?” Naomi pulled the light chain, and the bulb blinked on, revealing two more children crowded into the back of the closet.

Cari jumped up.

“When did you take these things?” Naomi pointed at the floor. “You had no right.”

“She was our mami, too.” Cari's chin jutted out. “Right, Beto?”

Beto kept his eyes on the floorboards.

“Hey, am I gonna get my nickel back?” A freckled boy standing in the back crossed his arms. “This ain't no say-dance.”

“Séance. And it's gonna be, just hang on.” Cari flashed a salesman's quick smile, but Naomi wasn't buying. She blew out the candles and grabbed her mother's shoes and tucked them under her arm. She cradled the braid.

“They're too small for you,” Cari said, “and anyhow, my shoes are back in Miss Bell's room.”

Naomi pushed off her own worn black shoes and kicked them toward Cari.

“You promised us voodoo,” a girl by the brooms whined, fingers twined in her stringy bob.

“It's called spiritualism,” Beto whispered.

“Back to class, now.” As she said it, Naomi looked at each child. They shifted to their feet but didn't meet her gaze. Except Cari.

“It's not fair,” Cari said. “Why should everything be yours? Why didn't she leave us something?”

Naomi stiffened. “She did. She left me.”

“Well, we want her.”

“Yeah? I do, too. But I lost her when you were born, so let's not talk about fair.” As soon as the words were out, Naomi wished she could snatch them back. Cari's face turned to stone. Tears slid down Beto's nose.

“Go back to class,” Naomi said again. She could hear the coldness in her own voice. Later, she'd explain. Later, she'd make the twins understand.

“Yes, ma'am,” the girl with the bobbed hair said.

“Hey, I still want my nickel back.” The freckled boy reached for Cari's sleeve.

She shook him off and stared at Naomi. “I hate you,” she whispered. She shoved her feet into Naomi's shoes, pushed out of the closet, and clomped across the cafeteria. Beto and the others hurried after her.

Naomi followed them partway, seeing them out the cafeteria door. Only Beto looked back, his face a plea she could not answer, not now. She watched from the window as they trudged along the long sidewalk back into the main school building. Once she'd seen them go inside, she gripped the braid tight and stumbled back to the closet.

The mindless, mechanical ease she'd managed was now gone. Reality settled on her shoulders, and she felt the cruel weight of it. It was her mother's birthday. She was engaged to her stepfather. The twins hated her.

Â

BETO

Beto got back to Miss Bell's classroom half a minute before Cari, who refused to hurry.

He slid into his seat in the desk he usually shared with Cari. Not today he wouldn't, though.

“Deenie.” Beto leaned across the aisle to whisper to the pale girl with red hair. “Come sit next to me.”

Deenie hesitated for a moment and then slid over into Cari's seat.

Cari arrived just in time to see her place being taken. She glared at Beto but spoke to Deenie. “That's my spot.”

“No, that's just as well,” Miss Bell said from the front of the room. “You and Robbie should be separated after your misbehavior. Ida Mae's absent; come take her seat up here, Carrie. I'll be by with your punishment.”

Cari shot Beto an angry look and then marched to the empty seat at the front of the room. Even the back of Cari's neck looked mad. That was fine with him; her anger was proof he'd been on Naomi's side. This time, Cari had gone too far.

Miss Bell handed him a scrap of paper. “A hundred times,” she said sternly. “I expect exemplary penmanship.”

He had not yet opened his notebook, but he could already hear the explosive scratch of Cari's pencil across her page. She could blast through a punishment in half the time it took him. He knew exactly how she was writing her hundred lines:

I will not play truant when I should be learning my lessons.

I will not play truant when I should be learning

I will not play truant when I

I will not play truant

I will not play

I will not

I will

I

I

I

Â

NAOMI

Naomi winced with each step back to the home economics cottage. Her heels hung off the back of her mother's shoes; she could not even buckle the straps. She averted her eyes as she limped past the wall of the gymnasium where a few mothers had ducked out of the afternoon PTA meeting to smoke. The school buses were lined up in the side parking lot of the school, waiting to be filled with kids who lived too far out in the county to walk home. The final bell would ring soon. She had to think. She had to figure out what she was going to do with Beto and Cari. She had to make them understand.

She would do better. She would find some way to give them a part of the truth about Estella's last days. And when the time came, maybe that would help them understand why they had to leave East Texasâand Henryâbehind.

Naomi bit her lip, exhausted all over again by the complicated dance she was going to have to do during the coming weeks and months. She wished things could just go on as they had been, the four of them in the woods, laughing and playing without a plan. Carefree. Careless.

There was no point in dwelling on it. Instead, she forced herself to envision the dress she would make for Cari. An apology dress. Layers of bright red sandwiched with a pink floral pattern. She would let Cari wear their mother's red shoes with it. A double peace offering.

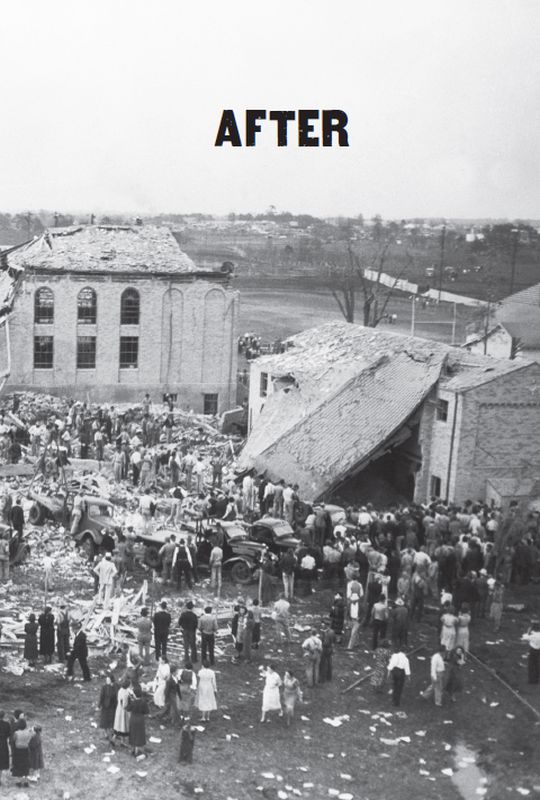

As she climbed the front steps of the cottage, she thought about what she might give to Beto. Then she realized that she had forgotten the baking soda. She was turning back to the cafeteria when the blast knocked her off her feet. She hit the edge of the porch and rolled onto her side. The earth rippled under her. From the ground, she watched the roof of the school rise up and rip open in a fountain of debris. Then it all came down. She held her arms over her face against bits of falling brick and wood and concrete. Something smacked wet against the porch steps. Naomi felt a splatter against her arms.

There was screaming from inside the cottage. Naomi pulled her arms away from her face and rolled onto her stomach. Chunks of brick littered the grass in front of her. A lunch pail. A splintered slate. She reached out and touched a bit of denim. Her hand came back wet with blood. She pushed herself up on her elbows and managed to sit. There were bodies across the lawn. People, lying there.

She needed to get up. She needed to help. She needed to find the twins. But instead, she sat in the dirt, arms at her side. It was a leg inside the denim, she realized now. Her brain was catching up. Go, go, she thought, but her body refused to obey. She stared through the clouds of dust at the cafeteria, which was still standing. Then she looked again at the shattered school building into which she had just sent Cari, Beto, and the others.

THURSDAY, MARCH 18, 1937, 3:25 P.M.

BETO

Screams and shouts filtered into Beto's brain. He thought of flour. He thought of chalk.

His eyelids were sealed shut. Vaguely he remembered being punched in the stomach. Then a roar and a long whiteness. But nowânow he was floating.

Beto forced one eye open, then the other. He saw blue sky. Wash's face. Wash was carrying him. Beto closed his eyes and tried not to know what he knew.

â â â

The second time Beto woke up, it was to the sound of Naomi's voice. She was talking to Wash, and Beto saw the look that passed between them before they knew he was watching. And he knew a second thing that he did not know how to live with: neither of them belonged to him. They belonged to each other.

Naomi said something again, but Beto didn't hear. He didn't blink. He didn't ask her about the look. He could only think: Cari, Cari, Cari.

Â

NAOMI

Naomi rocked Beto in her arms and stared, numb. Teachers and students stumbled around them. Mothers from the PTA meeting called the names of their children and clutched at each other. Men from the oil field arrived in truckloads. They ran into the school and came out carrying injured children. Also bodies. The dead were laid out in rows on the sparse grass. She watched and watched, but Wash did not come out.

“Wash is going to get her,” she whispered into Beto's hair. “He'll be back soon.”

Â

WASH

Wash was pushing aside a desk when he saw it: Naomi's other shoe. This time, the shoe wasn't empty. He recognized the gray and blue stripes of Cari's sock sticking out from under a fallen bookcase. He sucked in a deep breath and began emptying the shelves. When the books were mostly out, he flipped the bookcase over.

His pulse pounded in his ears. His mouth went dry. There was no right way to do what had to be done. He took off his jacket and wrapped Cari's leg in it.

Then he looked for the rest of her.

He told himself that he needed to hurry, that she was losing a lot of blood. He told himself that because it made it easier to search.

He heard a shout of “Everybody out!” just as he saw the plaid of Cari's good dress showing under a block of concrete. The walls groaned around him. Plaster began to fall in chunks. He ran to the spot and fought and fought to shift the block. He could not move it, could not move it, and then he could and he did and he found her. Her face was flattened. A trickle of blood marked her temple. More was matted in her pale hair.

He lifted Cari onto his shoulder, scooped up his jacket, and ran.

Â

BETO

Beto lay still and silent with his head in Naomi's lap. His eyes were glued to the bottom level of the building's east wing, which was where the third grade classroom had been, which was where Wash was looking for Cari. Now two men were helping Deenie Edwards through the doorway of the school. He wanted it to be Cari instead. He wanted it with all of himself. He wanted it even if that meant wishing for it not to be Deenie. Deenie with freckles and carrot-colored hair. Deenie who liked him. Deenie who had been sitting in Cari's seat.

The east wing began to move.

It shifted to the right. Farther and farther until it looked like a crooked drawing. And then it fell. Beto stared at the roof of the building, now on the ground. Naomi's cry was a live thing in the air.

Â

WASH

Wash carried Cari's body around the back of the building, shaking with the closeness of the call. A man in overalls ran past him, muttering, “Damn lucky, damn lucky.”

Wash couldn't call it luck, not with Cari like this. He tried not to think of all the ways she was broken.

Naomi and Beto would have to see her, he knew, but he would tell them first. Try to prepare them. He laid Cari beside a flimsy crepe myrtle sapling he'd planted the spring before. He placed the leg under the hem of her plaid dress and spread his jacket over her.

Â

NAOMI

Naomi stood by Beto as a man with round glasses and shaky hands examined him. She stared numbly at the school building.

She almost laughed with relief when she saw Wash walking toward them. Then she saw his face. “You didn't find her.”

Wash swallowed and wiped his hands down his pant legs. He eyed the doctor cautiously. “I did,” he said finally. He did not look at her.

“Well, where is she? Is she hurt?” Naomi asked. She did not let herself think.

“I was too late. IâI think it happened at the moment of the blast.”

“She's dead?” The blunt words surprised even Naomi. She felt the finality of it. A dark curtain falling. No more. No more.

She looked at Beto. His face was frozen and gray, but tears rivered down his cheeks.

“We need to see her,” Naomi said. She turned to the young doctor. “Can we go now?”

He frowned. “He might have a broken rib or two, but there's not much to do about that. Just keep a close eye on him.” He nodded at the three of them and walked on to the next injured child.