Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (21 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

The Jaffa-based Ottoman Commercial Committee issued the following decree to the “sons of the homeland” invoking the help of God as well as appealing to public opinion and observance to uphold Ottoman unity and promote Ottoman national interests. “We must prevent the sale of every piece of Austrian merchandise and clothing…; we must work with all our Ottoman capital, our businesses, and we hope that we will preserve that which is demanded of us by our heart, our homeland, our honor, and our conscience, and God is great and lofty and he is vigilant over the masses.”

38

Simultaneously, Jerusalem mayor Husayn Hashem al-Husayni issued a public flyer announcing the boycott to the local populace in similar terms, demanding compliance with the boycott as a sign of loyalty and patriotism to the Ottoman nation. In his words: “There is no doubt that

whoever does other than this will expose himself as betraying the homeland, civilization, and Islam.”

39

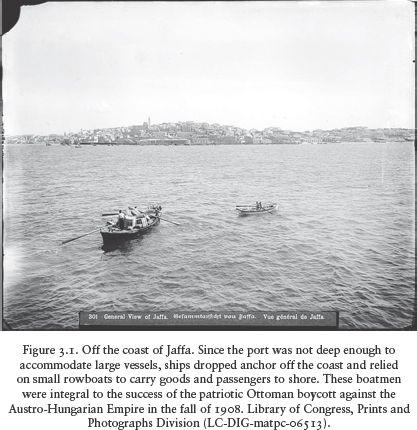

In response to these calls, the first public actions against local vestiges of Austria-Hungary's existence took effect on October 13, upon the arrival of a ship of the Österreichischen Lloyd Company to Jaffa's coastline. Because of the poor condition of the Jaffa port that did not allow large ships to actually dock at the harbor, instead ships dropped anchor offshore and small boats were hired to ferry goods and passengers to land. These port boatmen played a critical role in the Jaffa boycott, for without them, there was no possibility of reaching the shore. They refused to allow the government health commissioners onboard to disinfect the ship and refused to unload the ship's mail for the Austrian postal service. According to German consular reports, the quarantine

boat was attacked, its officials beaten, and disinfection tools destroyed.

40

The same morning of these tense events at the port, massive popular unrest and near rioting spread in the town and the incoming mail delivery and local office of the Austrian post were attacked. According to the report of the postal director to the Austrian Consulate, a crowd gathered at the post office incited by ringleaders and “fanatical” Muslim clerics.

41

They forced themselves inside “with insulting cries,” attacked the postal clerk Tawfiq Lorenzo, threatened the other clerks, and forced the clerks outside while demanding they shut down the post office. Egged on by the cries of the assembled crowd, the rioters pulled the mailbox from the wall, threw it in the mud, and trampled it underfoot. The postal wagon was attacked and partially destroyed before it was thrown into the sea, and the sign of the post office would have been removed and destroyed but for the efforts of the post office director.

The Austrian and German reports surrounding the boycott were damning, describing fanatical mobs pushed into a frenzy by zealous and diabolical clerics, aided and abetted by incompetent and perhaps complicit local officials and police. The Austrians further claimed that the demonstrations against them were far from spontaneous, but rather were conceived of by the central headquarters of the CUP, which they characterized as both authoritarian and “fanatically Eastern.” As well, the Austro-Hungarian consul in Jaffa emphasized the coercive nature of the boycott, alleging that the boatmen had been threatened that their boats would be destroyed if they assisted the Austrian ship.

42

By seeking to portray the boycott and mass mobilization as the machinations of a few fanatics, the Austro-Hungarian representatives sought to undermine the legitimacy of the boycott. In the eyes of European observers, instead of being a possibly legitimate form of political protest against the foreign policy of Austria-Hungary, the boycott was instead another sign of the backwardness of the empire and another front in the timeless clash of Western and Eastern civilizations. They reported that the crowds invoked Islamic and strongly anti-Western sentiments:

“dīn Muhammad qām bi al-sayf”

—the religion of Muhammad rose up by the sword;

“Allah yan ur al-sul

ur al-sul ān”

ān”

—God will make the sultan victorious; and

“Allah yahlik al-kuffār”

—God will destroy the infidels.

Without doubt, popular anger tapped into a longer historical consciousness of European-Ottoman and Christian-Islamic clashes and tensions. On the popular level, encroaching Western powers were visible daily in the Capitulation system, the brashness of many foreign consuls and residents, and the recurring visits of Western warships along the Ottoman coast that constantly threatened to undermine Ottoman sovereignty

once and for all. In the aftermath of the July revolution, then, further concessions to the West were too much to bear, at least not silently. One newspaper confirmed that participants in a Jaffa demonstration waved “sacred flags.”

43

However, it is inaccurate to see this boycott as a purely Muslim versus Christian conflict; rather, Islamic discourse was rallied alongside Ottoman patriotism. Importantly, Muslims were not the only participants in the imperial boycott, and in many locations Christians and Jews were also active as organizers, mobilizers, and participants. When the mass demonstrations spread inland to Jerusalem, they were led by the Mufti Taher al-Husayni, but he was joined by Jewish, Greek Orthodox, and Armenian representatives who were elected to serve alongside him on a boycott committee.

44

In mid-November 1908, the Greek Orthodox community of Jaffa organized a play entitled

Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi

, where all the major European powers were represented, the Austro-Hungarian monarch represented by a “poor Polish Jew” who was the butt of the jokes of the play. In attendance were Jaffa's honorable Christian families, who shouted, “Down with Austria!” at the appearance of the emperor-Jew.

45

Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi, known as Saladin in the West, had pushed back the Christian crusaders from Egypt and liberated Palestine after almost one hundred years of Crusader rule in which thousands of local Muslims, Jews, and Christians had been killed. For this he is considered a great hero in Islamic and Arab history, a symbol of Islamic and Arab liberation from Western aggression as well as of Islamic tolerance, for unlike the Crusaders, Salah al-Din did not massacre non-Muslims but rather allowed them to live alongside their neighbors.

Due to both a shared language and social proximity, many Christian Arabs were steeped in Islamic civilization, history, and tradition, so the turn of Jaffa's Greek Orthodox community to the legacy of Salah al-Din is not unusual in and of itself.

46

However, the fact that the Greek Orthodox community in Jaffa was so supportive of the boycott—indeed several of the local CUP organizers themselves were Greek Orthodox—is significant in another respect. Some historians have seen the boycott as highlighting the divergent interests of non-Muslims, overrepresented in the commercial and merchant classes, and Muslims, underrepresented in those areas. As the Ottoman historian Donald Quataert has written, the boycott “exposed the fragile position of Ottoman Christians, living in a Muslim society but dependent on the Western economy. By highlighting the different interests of the non-Muslim and Muslim merchant communities, it hastened the disappearance of Christians from the commercial and industrial life of the Ottoman Empire.”

47

To be sure, the boycott was the first step heralding a broader turn toward creating an Ottoman “national economy”

(milli iktisat)

, but one important component of that was overcoming the Ottoman Empire's uneven economic position as a consumer of European finished products while providing only raw materials for export. To that end the Ottoman press encouraged the entire Ottoman population to buy nationally produced goods at the same time that it encouraged the government and the capitalist classes to build up a national industry.

48

The Izmir-based Greek Orthodox newspaper

Amaltheia

was one of the most vocal proponents of economic protectionism, taking a hard-line view that Ottoman citizens should only purchase Ottoman-made goods, even if that meant forgoing products for which there was no local equivalent.

49

Certainly few parties were interested in allowing the economic boycott to introduce cracks in Ottoman unity, and there is some evidence that the local CUP leadership tried to moderate the public cries of the crowds.

50

There is no evidence, however, that Christian Ottomans were targeted by the crowds, but rather they were given an opportunity to display their Ottoman patriotism and commitment to the imperial public good.

In the meantime, the Austrian ship had been kept waiting off the shores of Jaffa for several days; the crowds reportedly threatened to bomb and attack the ship if it was allowed to land and unload its passengers or goods. Instead, the ship was rerouted to either Beirut or Cyprus and the mass demonstrations ended. Immediately afterward, the Ottoman governor sent forty gendarmes and three infantry companies from Jerusalem to Jaffa to keep order. A passing European warship was also believed to have a “salutary” and “calming” effect on the public's mood, at least according to the German Consulate; arguably the effect would have been more akin to “intimidating” from the Ottoman perspective.

51

The boycott continued, however, and within a few days it had spread to target Austro-Hungarian shops and goods already on store shelves.

52

By the beginning of November, the Jaffa boycott widened to target German ships and goods as well, based on the claim that Austrian goods were being shipped on German boats and sold under false German labels. A flyer that survived from the period, signed by “Zealous Ottoman Patriot [‘Uthmān watānī ghayūr],” made this claim, linking the boycott, Ottoman patriotism, religion, and the force of society in marking and protecting social and political boundaries. The flyer was addressed to and written by those who identified themselves with the Ottoman nation; the flyer's exhortations were based on Ottoman national feelings; and the people were elevated to the level of legitimate enforcer of nationalism.

Now we hear that the Austrian goods are coming by way of German ships via Germany. [Those of you partaking of this], if you do not fear Allah then at least

be ashamed before the people and be embarrassed that…it will be said that even the poor people are greater than you…and are more patriotic than you.

No. No. God forbid, we do not believe that…there are people in the world who are released from human feelings and are greedy for profits from the port customs…. Likewise we do not believe that there are merchants who use this national zeal in order to raise the price of their goods. So, sons of the homeland, shame on us for hearing such a thing as these deeds, and we must point a finger publicly at the man who does them, and fathers must show their children while saying, “There goes the man who sold his patriotism out of his desire to fill his coffers,” and he will earn the anger of Allah and the contempt of the people.

53