Oral Literature in Africa (77 page)

Read Oral Literature in Africa Online

Authors: Ruth Finnegan

Boahen Kojo,

Whence was it that thou camest?

Thou camest from Mampon Akurofonso,

The place where the Creator made things.

Adu Gyamfi with an eye like flint, (whose title is) Ampafrako.

The Shadows were falling cool,

They fell cool for me at Sekyire

27

The day dawned, It dawned for me at Sekyire, Who is Chief of Sekyire?

The Chief of Sekyire is Kwaitu, Kwaaye knows Afrane Akwa, Boatimpon

Akuamoa,

Akuamoa,

28

whom we even grow weary of thanking, for his gifts,

Akuamoa, you were of the royal blood since long, long ago,

Thou earnest from Mampon Kontonkyi, where the rock wears away the axe.

Kon!

Akuamoa Firampon,

Alas!

Alas!

29

III

Drum language, it is clear, is a medium that can be put to a wide range of uses. Its appearance in messages, in names, in poetry, and in the performance of proverbs has been illustrated. It can also be employed to comment on or add to some current activity. Armstrong, for example, describes the actions of a chief drummer at a dance in the Benue-Cross River area, in words that could be applied elsewhere too: he

maintains a running commentary on the dance, controls the line dancers with great precision, calls particular persons by name to dance solo, tells them what dance to do, corrects them as they do it, and sends them back into line with comment on the performance. He does this by making his drum talk, even above the sound of four or five other drums in the ‘orchestra’.

(Armstrong 1954: 360)

In this example, the ‘speaking’ and comment of the drum form a linguistic complement, as it were, to the musical and balletic aspects of the artistic event as a whole. Among the Kele, the talking drum accompanies wrestling matches, saluting contestants as they enter the ring, uttering comment and encouragement throughout the fight, and ending up with praise for the victor (Carrington 1949

a

: 63–4). Similar literary contributions are made by the drums among the Akan even to the otherwise mundane duty of carrying the chief. It is raised to a state ceremonial by the conventions surrounding it and by the drum poetry that accompanies and comments on it: the drums say ‘I carry father: I carry father, he is too heavy for me’, to which the bass drum replies, in conventional form, ‘Can’t cut bits off him to make him lighter’ (Nketia 1963

b

: 135). In funerals too, Akan drums play their part, echoing the themes of dirges and heralding the occasion with messages of condolence and farewell (Ibid.: 64). Such comment by drums can take so elaborate a form as to be classed as full drum poetry in its own right. In this case it covers the sorts of drum proverbs, panegyrics, and histories already quoted, forming a specialized type of poetry apparently most characteristic of certain traditional states of West Africa.

Expression by drums or other instruments can also be an alternative medium to the human voice through which ordinary poetry can be represented. Thus among the Yoruba each of their many types of poetry can be recited on the drum as well as spoken, and the

oriki

(praise) poems are as frequently drummed as sung (Lasebikan in Osadebay 1949: 154; Gbadamosi and Beier 1959: 9). With the Akan some poems can be

drummed or sung, others are designed specifically for voice, drums, or horns respectively (Nketia in Osadebay 1949: 156).

Many different kinds of communications, then, can be conveyed through the medium of drum language—messages, public announcements, comment, and many types of poetry—and the same sorts of functions can be fulfilled as by the corresponding speech forms, with the additional attributes of the greater publicity and impressiveness of the drum performance. In spite of its wide range of uses, however, drum communication is in certain respects a somewhat limited medium. There are limitations, that is, on the types of communications that can be transmitted; the stereotyped phrases for use in drum languages do not cover every sphere of life, but only the content conventionally expected to be communicated through drums.

30

Furthermore, in certain societies at least (for example, the Yoruba and the Akan), drumming is a highly specialized activity, with a period of apprenticeship and exclusive membership, so that to a greater extent than in most forms of spoken art, drum literature is a relatively esoteric and specialized form of expression, understood by many (at least in its simpler forms) but probably only fully mastered and appreciated by the few.

31

In the case of some peoples the response to such limitations has been the creation of a highly elaborate and conventional mode of artistic expression through drums—with the apparent corollary that in this very specialized and difficult medium the scope for individual variation and improvization seems to be correspondingly limited and the stress laid on technical mastery rather than on verbal originality.

32

In conclusion it must be stressed again that what is transmitted in drum language is a direct representation of the words themselves. This is worth repeating, because for someone unacquainted with this medium it is not easy to grasp that the drums actually speak words, that from the point of

view both of the analyst and of the people involved, the basis is a directly linguistic one. From this it follows that the content and style of drum communication can often be assessed as literature, and not primarily as music, signal codes, or incidental accompaniment to dancing or ceremonies. Some of the items of drum language that have been mentioned—the ‘proverb-like’ phrases of Kele drum language, for instance, or the whistled names in the Upper Volta—are only marginally literary. Other forms, however, in particular the drum poems of southern Ghana, Nigeria, and Dahomey, unmistakably fall into the category of highly developed oral literature. But whatever the assessment of individual examples it is clear that it is both correct and illuminating to analyse drum language in terms of its literary significance. Among the people who practise it, drum literature is clearly a part, albeit through a highly specialized and unusual medium, of their whole oral literature.

33

Footnotes

1

The description in this chapter is mainly based on Rattray 1923; Carrington 1944, 1949a, 1949b; and Nketia 1963b. Nketia’s book forms the first part (all as yet available) of his detailed analysis of various aspects of Akan drumming; the second volume is to discuss drum poetry in more detail.

1

Generic drum name for Europeans. The reference is to the very large leaves used for roof tiles, compared to the Bible.

2

Common drum phrase for house.

3

There are sometimes additional complications in practice: e.g. in Kalabari, a language with three tones, these are abstracted into a two-tone basis for drumming (Horton 1963: 98 n.); in Yoruba tonal glides are sometimes represented, sometimes not (Beier 195: 29–30); in the Congo it is the essential word tones that are transmitted and not the modifications of these as they would actually be pronounced in a spoken sentence (Carrington 1949

b

: 59). But the basic principle of representation of the tones of words seems to apply throughout.

4

Drum messages can be heard at a distance of between three to seven miles, according to Carrington 1949

b

: 25.

5

Strictly the term ‘gong’ should be used to refer to the hollow wooden ideophones or ‘slit-gongs’ typical of the Congo area; whereas ‘drum’, which I have used in a wide sense here, should be confined to membranophones such as the Ashanti ‘talking drums’, a pair of hide-covered drums, one sounding a high, the other a low tone. Other media mentioned for this type of communication include horns, bells, yodelling of various types, sticks, a blacksmith’s hammer and anvil, stringed instruments, and whistling.

6

Among the Kele the idea that drum names are part of their oral literature also comes out in their terminology, if Carrington is right in deriving bombila (drum name) from the same root as that for ‘story’ or ‘parable’ (Carrington 1944: 83).

7

Title of a person present.

8

i.e. keep quiet everyone.

9

Meaning unknown; a title?

10

i.e. ‘A patient person’; title of someone present.

11

i.e. ‘A precise man’; title of someone present.

12

i.e. ‘the people have all come together’.

13

i.e. ‘Here is a chief; chiefly praise.

14

i.e. ‘The royal people have assembled’.

15

i. e. ‘Come on, girls, get out and dance’.

16

‘Head’ here stands for the Yoruba ‘ori’ which means: head, good fortune or luck. People sacrifice to their head as thanksgiving for success, etc.

17

Yoruba spirits.

18

Yoruba spirits.

19

They are trying to do the impossible.

20

Trying to conciliate your opponents, show respect—but not too much because you are the oba (king).

21

During the chieftaincy dispute all the contestants were confused by the sudden appearance of Adetoyese Laoye.

22

Policemen. The reference is to the cummerbund on the Native Authority Police uniform. During the contest police had to be transferred from Ede because they were alleged to favour one of the contestants.

23

A locality on the Gold Coast.

24

The drummer of the talking drums, a powerful figure, is commonly referred to as the ‘divine drummer’ or ‘Creator’s drummer’ (Nketia 1963b: 54).

25

The first Queen Mother of the Beretuo clan, said to have descended from the sky. She was head of the clan before they migrated to Mampon.

26

Strong names (titles).

27

The name of the wider region that includes Mampon.

28

The sixth ruler of the Beretuo clan.

29

Rattray 1923: 378–82, stanzas II, IV, V, VIII, IX, XII, XIII. He reproduces the poem in drum language, in ordinary Ashanti, and in English translation.

30

Or so it seems. With the exception of some remarks in Rattray (1923: 256–7), the sources do not discuss this point directly.

31

Not much has been written about the distribution of this skill among the population generally and further study of this question is desirable. Its prevalence in the contemporary scene also demands research; clearly it is at times highly relevant as, for instance, in the use of drum language over the radio during the Nigerian civil war to convey a message to certain listeners, and conceal it from others.

32

Again, further evidence on this point would be welcome. Of the Akan Nketia makes the point that all drum texts are ‘traditional’ (apart from the nonsense syllables sometimes included in them which may be invented) and that many are known in the same form to drummers in widely separate areas (1963

b

: 48).

33

There is a huge (and very variable) literature on drum language that it is impossible to begin to cover here. Useful bibliographies are to be found in Carrington 1949

b

, and T. Stern 1957. Cf. also, among many other accounts: Witte 1910 (Ewe); Jacobs 1959; Schneider 1952 (Duala); Van Avermaet 1945; Armstrong 1955; Hulstaert 1935; Labouret 1923; Herzog (reprinted in Hymes 1964).

18. Drama

Introductory. Some minor examples: Bushman ‘plays’; West African puppet shows. Mande comedies. West African masquerades: South-Eastern Nigeria; Kalahari. Conclusion

.

I

How far one can speak of indigenous drama in Africa is not an easy question. In this it differs from previous topics like, say, panegyric, political poetry, or prose narratives, for there it was easy to discover African analogies to the familiar European forms. Though some writers have very positively affirmed the existence of native African drama (Traoré 1958, Delafosse 1916), it would perhaps be truer to say that in Africa, in contrast to Western Europe and Asia, drama is not typically a wide-spread or a developed form.

There are, however, certain dramatic and quasi-dramatic phenomena to be found, particularly in parts of West Africa. Many are of great interest in themselves, particularly, perhaps, the celebrated masquerades of Southern Nigeria. Furthermore, some discussion of such elements of drama helps to throw light on oral literature in general in Africa.

There are other reasons why some discussion of ‘drama’ in Africa is essential. The subject is in many minds inextricably linked to the question of the origin of drama and to the interpretations of a particular critical school. The existence and supposed nature of drama, mimetic dances, or masquerades in Africa have been taken as evidence in discussions of the origin of drama. While many would now reject the assumptions (often inspired by Frazer’s

Golden Bough

) that are inherent in the evolutionist approach, works built on such assumptions still circulate widely and provoke an interest in the question of what sort of drama can be found in Africa.

1

It is, in fact, natural that students of the nature and

history of European drama should be interested in comparative evidence of analogous forms in Africa. In addition, interpretations of literature in terms of myth and archetype might at first sight be expected to draw particular support from a knowledge of African dramatic forms.

It is clearly necessary to reach at least some rough agreement about what is to count as ‘drama’. Rather than produce a verbal definition, it seems better to point to the various elements which tend to come together in what, in the wide sense, we normally regard as drama. Most important is the idea of enactment, of representation through actors who imitate persons and events. This is also usually associated with other elements, appearing to a greater or lesser degree at different times or places: linguistic content; plot; the represented interaction of several characters; specialized scenery, etc.; often music; and—of particular importance in most African performances—dance.

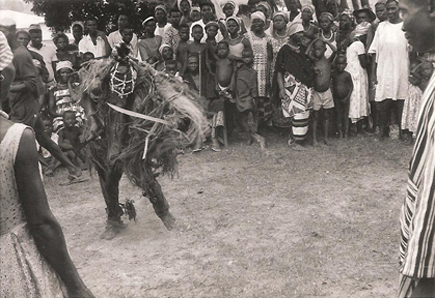

Figure 25. Masked Limba dancer and supporters, Kakarima, 1962 (photo Ruth Finnegan).

Now it is very seldom in Africa that all these elements of drama come together in a single performance. One or several do of course occur frequently. But which, if any, of such performances are counted as fully ‘drama’ will depend on which of the various elements mentioned above are considered as most significant (a point, of course, that applies to more than

just African dramatic performances). What is clear is that while dramatic elements enter into several different categories of artistic activity in Africa and are thus worth consideration here, there are few or no performances which obviously and immediately include all these dramatic elements.

2

In order to bring out the respective significance of these various elements we will look first at some minor forms. This will be followed by a discussion of the more obviously dramatic forms of West Africa—the comedies of the Mande-speaking area and the complicated masquerades of South-Eastern Nigeria.

II

The emphasis on histrionic ability in story-telling has already been mentioned.

3

Stories are often enacted in the sense that, to a greater or smaller degree, the speech and gestures of their characters are imitated by the narrator, and the action is largely exhibited through dialogue in which the story-teller directly portrays various characters in turn. It is true that such enactment of character is not sustained or complete, that straight narration, as well as dramatic dialogue, is used to communicate the events of the story, and that only one real ‘actor’ could be said to be involved; thus story-telling can only be spoken of as possessing certain dramatic characteristics, rather than being ‘drama’ in the full sense. Nevertheless, these dramatic aspects are of the greatest importance in the telling of stories. It has been said of written literature that drama, unlike prose narrative, is not ‘self-contained’ but depends on other additional elements for its full effect. Precisely the same point could be made of oral narration. As Delafosse writes of certain storytellers in the Ivory Coast: ‘J’ai entendu des griots raconter des histoires au cours desquelles ils faisaient parler leurs héros et qui devenaient dans leur bouche de véritables scènes de théâtre à personnages multiples représentés par un acteur unique (Delafosse 1916: 355).

This similarity to dramatic performance is heightened by the frequent occurrence of music and sometimes even rudimentary dance movements. It is common for the story-teller to begin a song in the course of the narration—often a song sung by, or representing the actions of, one of the

characters—and for this to be taken up antiphonally by the audience acting as chorus, in this way partaking in the dramatic enactment of the story. Occasionally too the storyteller stands and moves among the audience. If most African peoples lack specialized drama, they yet, by the very oral nature of their art, lay greater stress on certain dramatic characteristics of their literature than do cultures that rely primarily on written forms.

A very different side of dramatic art is exhibited by the Khomani Bushman plays described by Doke (Doke 1936; cf. also Schapera 1930: 203ff). Here the linguistic element is apparently non-existent, but the action is portrayed completely through the imitation of several actors. Among the southern Bushmen in particular, there is also some attempt to make themselves up to resemble the animals represented by using paint, or the skins or horns of animals. These ‘dramas of the desert’ (Doke 1936: 465)

.

represent the different stages in hunting. Doke describes ten of these plays, and considers that since they depend on imitation and mimicry they have to be considered as drama. In the ‘springbok and lion play’, for instance, the various animals are portrayed: the girls take the part of the springboks, with the little children as kids, while two or three men act the lions. First the kids, then the springboks are shown as being stalked by the lions with a vividness that makes it into ‘a very exciting drama’ (Doke 1936: 466). ‘The gemsbok play’ Doke regards as ‘probably the Bushman masterpiece of dramatic representation’ (Doke 1936: 467). In it, one man acts the part of the gemsbok, with a forked stick tied or held to his forehead to represent the horns, and imitates its actions and gait. He is pursued by three or four armed huntsmen and by boys acting as dogs who look out the spoor. The gemsbok is chased, then finally turns at bay. After an exciting fight the play is ended by the death and dispatch of the gemsbok by the hunters and their dogs.

It is possible that similar mimicry and dramatization, particularly of hunting, occur elsewhere in Africa. However, I know of no descriptions of such plays (or dramatic performances of any other kind) from Bantu Africa as a whole, with perhaps the exception of a certain dramatization sometimes found in rituals like initiation and funeral rites.

4

For our other examples of dramatic or quasi-dramatic phenomena we must turn to West

Africa, where we can find more elaborate forms ranging from mere puppet shows to the plays of the Mande-speaking peoples of the savannah areas and the masquerades mainly typical of the forest region. These can be discussed in turn.

There are several passing references to puppets in West Africa, though, it seems, few detailed descriptions of their performances. They have been recorded as appearing, in various forms, in the north of the Ivory Coast, in Bornu, Zaria, Bida, and other places in Northern Nigeria and Niger, and occasionally in Southern Nigeria (Delafosse 1916: 355; Ellison 1935; Labouret and Travélé 1928; Murray 1939: 218; Pageard 1962). It is uncertain how long a history they have in these areas.

5

One detailed description has been given of a puppet show in Bornu (Ellison 1935). Here the puppets consist of rag dolls that fit over the manipulator’s hand rather like gloves and are shown through the opening in a kind of tent made by draping a large gown over a stick planted in the ground. The manipulator speaks for the puppets in a special voice produced by half swallowing pieces of ostrich egg-shell; the shrill whistle that results is barely intelligible and the words are therefore repeated by an assistant standing by. In the performance that Ellison witnessed there were eight short scenes, each lasting three to four minutes and complete in itself. Only two puppets could appear at a time, but there were about six in all, and during the intervals while they were being changed inside the tent, the audience were entertained by drummers and singers. The scenes portrayed involved a clear plot, speech, suitable costumes for the parts enacted, and dramatic and exaggerated action. One scene, for example, showed a thief entering a man’s house and on the point of making off with his booty when the owner’s wife wakes and gives the alarm; the husband appears and dramatically gives the thief a sound beating. Another included a coy Shuwa Arab girl dressed in a long flowing gown with cowries in her hair who sings and dances, and thus captivates a married man; he, inevitably, is caught by his wife and is scolded and beaten; and the scene ends with a realistic fight between the husband and a bystander who has come to see what is happening. A final example is about a rest-house keeper. He is told by the village head that the District Officer is coming—a very particular and fussy D.O., we are informed—and that the rest-house must be very well swept, and wood and water all provided with the greatest care. The D.O.

arrives dressed all in white, complete with white pith helmet, and is shown being greeted with exaggerated respect by the village head. But, the story continues, the rest-house turns out to be not exactly spotless and the scene ends with its keeper being severely reproved.

Are such shows to be called drama? Certainly they include most of the dramatic elements we have already mentioned: the enactment of character and events; several actors, albeit in puppet rather than human form; plot; linguistic content; specialized costume; and a limited amount of singing and dancing as well as interval music. In a way it seems unsuitable to call this form drama; and it is worth noting that even in Bornu it seems to have been relatively rarely practised and not regarded as a serious form of art. Still, it must be accepted that the plots and attitudes involved are very similar to some of those in the Mande ‘plays’ described later, and that even puppet shows can be used to comment comically and dramatically on the events and characters of everyday life.

III

Of much greater interest are the comedies of certain Mande-speaking peoples in the savannah areas of ex-French West Africa. These, perhaps alone among African enactments, would seem fully to satisfy most of the normal criteria for a truly dramatic play. They have clear plot and linguistic content, as well as music, dancing, costume, definite audience, and the interaction of several human actors appearing at once in the village square that acts as a stage. They are described as ‘véritables pièces parfaitement ordonnées et réglées, destinées à exposer une intrigue déterminée, en employant pour interpréter celle-ci des acteurs humains. On peut donc affirmer, dans ces conditions, qu’il existe bien un théâtre soudanais’ (Labouret and Travélé 1928: 74).

One group of these plays—those of the Mandingo—were described in some detail by Labouret and Travélé in 1928. They are all comic, intended for entertainment and the realistic portrayal of the characters and faults of everyday life. As implied by the Mandingo term kote koma nyaga, the plays treat especially of marriage and the various misfortunes of married life, but also involve satirical comment on many other aspects of life. The authors are also actors.

These comedies are said to have been performed every year in the Bamako and Bougouni

cercles

of what was then French Soudan, in the region of the old Mali kingdom. The normal occasion is after the harvest,

between October and March. In the evening the audience is called to the open village square where, with no scenery or special building, the comedies are presented in the open air, lit either by the moon or by lanterns and candles. Each evening’s entertainment follows a fixed order which Labouret and Travélé term respectively the opening ballet (

kote don

), the prologue, the presentation of the players, and, finally, the plays proper.

The proceedings begin with the announcement of the

kote koma iiyaga

at about eight in the evening; people hurry to the square and sit ready, with the children running around among the spectators. The drum orchestra enters and takes its place in the centre, and the young men and women start to dance in a slow, circular movement. This makes up the opening ballet. Then the orchestra withdraws to the edge of the square and the choir of women and girls group themselves around it ready to take up the actors’ singing. Meanwhile the actors (almost always men) are preparing in a nearby house, dressing and making up by covering the face and body with clay or ash to create a fantastic or ridiculous appearance. They dress themselves for comic effect, with torn clothes and the various implements which they need for their roles.