Authors: Peter Hessler

Oracle Bones (77 page)

Your sight SUCKS! Iwant the Chinese Alphabet Now!

GET SOME CHINESE NAMES I THINK IT STINKS

YOUR WEBSITE S CKS THE BIG ONE !!!!

Hi I would like to make one comment on your web site. You are fucking stupid to name your website the chinese alphabet where is it. The reason because people are trying to find it not an explanation on why it is not around people just want the alphabet, so give it to them.

One of Galambos’s friends agreed that that was a good idea. “He said, ‘Why don’t you just give it to them?’” Galambos remembers. “So we sat down and tried to figure out what can pass for the Chinese alphabet. Somebody suggested that we send them the Chinese encoding page. It’s the Unicode values, the numbers for each character. Or send them the entire set of thirteen thousand characters and destroy their in-box.”

In the end, Galambos refrained from aggression. Nevertheless, he is slightly embarrassed about his response; after all, he is a serious scholar and a curator of ancient texts. But Americans kept asking him for Chinese writing: there was a clear demand, and it was up to him to supply something.

On his Web site, he posted Chinese versions of some English names—Cecilia, Jeremy, etc.—and priced them at ten dollars each. At first, business was slow: two hundred dollars a month. He redesigned the site, adding Chinese characters for things other than personal names. He also structured the site strategically, so that it would appear whenever somebody typed “Chinese symbols” into Google.

“It went up to about six hundred dollars a month,” he says. “I thought that was cool. Then I redesigned it again and it went up to about fifteen hundred dollars a month. In August it was about two grand for Chinese symbols. They’re just English words, more than a hundred. You choose the ones you want and you can buy them. You get a Web page that stays up for two weeks and you can download it or whatever. The most popular ones are ‘love,’ ‘faith,’ ‘fate,’ ‘friend,’ ‘brother,’ ‘elder brother,’ ‘younger brother,’ ‘sisters’—this sort of thing. Sometimes ‘God’ and ‘Jesus.’ I had the Holy Ghost up, but nobody bought it so I took it down. I put up the Western zodiac and that day everybody was buying them, so I was like, cool. So then I translated the page into Spanish and we have people ordering in Spanish as well. And I had an idea and I put up the Japanese symbols, and now maybe about twenty percent are coming from that. It’s two dollars and fifty cents per word, four symbols minimum. ‘Fate’ is $2.50.

“My sister in Hungary is not doing well, so I gave her the Web site. We split the money. Next I’m putting up the Egyptian symbols, and the Mayan symbols. Why not? Most people buy them for tattoos, but I get a few designers as well.”

He continues: “The site has been up for about a year, and since then I’ve seen some Chinese who are starting to do the same business on the Internet. But the Chinese cannot sell the characters by themselves. They have to put the character on a cup, or a pen, or a T-shirt, or whatever. They cannot seem to grasp the idea—people don’t need the cup or the T-shirt; they just need the fucking character. It doesn’t make sense to the Chinese. It’s like you selling the letter

B

to Mongolians.”

June 2002

A FRIEND OF THE OLD MAN DELIVERED THE TEA TO ME IN BEIJING.

The package consisted of two bags of dried leaves that had been picked from the Yellow Mountains of Anhui province. Late spring is the best season for tea and the sharp fresh smell filled my luggage during the flight across the Pacific.

While visiting Polat in Washington, D.C., I made a side trip to a retirement home in Reston, Virginia. Blue carpet, white walls, wheelchair rails—the place felt uniform and dull, the way that old age often appears from a distance. I followed silent hallways to apartment 823. A sticker on the door featured an American flag and the words “

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

.”

Wu Ningkun answered my knock, laughing with delight when I gave him the bags. “This is what they used for court tea in the old days,” he said. “Look at the green color—isn’t that beautiful? Later it will turn red, but when it’s fresh it still looks like this.”

He said the tea was something that he missed from China. Other than that, he didn’t have many complaints about his new American life. I sat down and he poured two glasses of Raynal French Brandy.

WU NINGKUN LIKED

to describe himself as a “war profiteer.” In 1937, the Japanese invaded his home province of Jiangsu, where, in the capital city, they committed the Nanjing Massacre. Wu, who was seventeen years old, fled westward. His childhood had not been happy—his mother committed suicide

when he was seven—and the life of a refugee gave the young man a new start. After finishing high school in Sichuan, he entered college in Kunming, where he studied English. He served as an interpreter for the volunteer pilots of the American “Flying Tigers,” who were fighting the Japanese from their base in Sichuan. After the war, Wu received a scholarship to Manchester College, in Indiana, where he was the only foreign student on campus. In 1948, he began to pursue a doctorate in English literature at the University of Chicago. Those were Wu Ningkun’s war profits—strictly educational.

After 1949, like other young Chinese in the United States, Wu was faced with a difficult decision. A number of Chicago grads returned to the New China, including Lucy Chao. From Beijing, she encouraged Wu to come back and teach, and finally he agreed. His dissertation—“The Critical Tradition of T. S. Eliot”

—

was left unfinished. One of his graduate-school friends, a young physicist named T. D. Lee, came to San Francisco to see him off. Wu asked his friend why he had decided to stay in the States. T. D. Lee replied, “I don’t want to have my brains washed by others.”

And so the story went. In 1955, Wu was named a Counter-Revolutionary; in 1957, he became a Rightist; in 1958, he was sent to a labor camp. For most of the next two decades, he lived either in jail or in exile in the countryside. Several times he nearly starved to death. But he survived, and so did his wife, Li Yikai, who, despite all the campaigns and punishments, never renounced her Catholic faith.

In 1990, Manchester College awarded Wu Ningkun an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters. At the college’s invitation, he stayed on campus to write a memoir in English,

A Single Tear

, which was published by Atlantic Monthly Press. After the book came out, Wu’s work unit in Beijing revoked his pension and housing rights. He and his wife decided to stay in the United States, where their three adult children had already settled after studying abroad. In 1996, Wu Ningkun and Li Yikai became naturalized citizens.

Occasionally, Wu contributed reports to the Voice of America (“they pay for my drinks”). In one broadcast, he reviewed my first book, and then he sent me a printed copy of the commentary. That chance contact pointed me toward the past: after Wu told me about his graduate-school friendship with Lucy Chao and Chen Mengjia, I became determined to pursue the story of the oracle bone scholar.

Wu Ningkun was eighty-two years old, with thick white hair, and he had a disarming tendency to laugh when he talked about the past. The years of awful persecution didn’t seem to weigh on him. He liked to tell another story

about T. D. Lee, the young physicist who had stayed in America because he preferred not to be brainwashed. In 1957, the year that Wu was named a Rightist, T. D. Lee became the second-youngest scientist ever to win a Nobel Prize.

“LET’S DRINK TO

Chen Mengjia and Lucy Chao, my big sister,” Wu said, using the common Chinese term of affection for a female friend. We raised our glasses, and then he stood up and went to his desk. He handed me two letters. “These are very personal,” he said.

Both had been handwritten in Chinese by Lucy in the early 1990s. One letter referred to Wu’s book, as well as the ancient courtyard that I had seen destroyed. She wrote:

I’m still excited about your publication…. You and Yikai can stay with me if you come to Beijing. Now I have a guest room in the west wing of the courtyard which is well equipped. And you can take meals with me.

“I was always sympathetic to her,” Wu said. “I didn’t think Old Mr. Zhao treated her very nicely. According to Lucy, her father wanted to leave the house to her, but at that time she was with Chen Mengjia, so she let her brother have the family home. And then Chen Mengjia killed himself, and she lost their house, so she had to move in with her brother and his wife. They occupied the best part and only gave her a small building. They didn’t treat her very nicely; the three of them didn’t even eat at the same table. A widowed sister, just after the Cultural Revolution—they should have been more solicitous of her! She just had these two little rooms.”

He continued, “Their characters were totally different. Old Mr. Zhao and his wife liked to play mah-jongg. And he liked playing tennis with Wan Li and other big shots. He didn’t really care about teaching English. They were busy playing mah-jongg while Lucy was translating Whitman!”

Wu took another sip of brandy. His small apartment was crowded with the decorations of two cultures, and the bookshelves shifted between languages: Joseph Brodsky, , Vladimir Nabokov,

, Vladimir Nabokov, John Keats. A photograph of Li Yikai with the pope hung on one wall, near pictures of the couple’s three children and their families. Two of Wu and Li’s children had married white Americans. (“Those are hybrids,” Wu said, pointing at his grandchildren’s photos.) On another wall hung a scroll of calligraphy written by the poet

John Keats. A photograph of Li Yikai with the pope hung on one wall, near pictures of the couple’s three children and their families. Two of Wu and Li’s children had married white Americans. (“Those are hybrids,” Wu said, pointing at his grandchildren’s photos.) On another wall hung a scroll of calligraphy written by the poet :

:

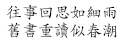

(Our memory of things past is like a light rain

Old books re-read are like the spring tide.)

I asked Wu Ningkun when he had first heard about Chen Mengjia’s suicide.

“Before the Cultural Revolution was over,” he said. “I heard through the grapevine when I was in Anhui. He was not the only one. I wouldn’t have done it. I could have been killed easily, because the Communists had all the bullets. They could have killed me anytime they wished, but I would not have done it myself. My mother did that and I wasn’t going to do it like that.”