Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love (5 page)

Read Oogy The Dog Only a Family Could Love Online

Authors: Larry Levin

Trauma is easier to overcome than long-term maltreatment, because abuse becomes a way of life and affects the dog’s spirits. Although the pup had suffered both trauma and abuse, because he was so young and neither had been prolonged, neither seemed to have had a permanent effect on him. He continued to heal and then began to flourish. His condition and the cruelty he had endured produced a heartfelt, deeply caring reaction among the hospital staff. His happy, affectionate nature was seemingly more pronounced because of the horror he had undergone. They warmed to him. As Diane described it, “He became everybody’s dog.” The entire staff participated in caring for the dog and nurturing him. Buoyant with optimism, after another ten days Diane took him home to begin fostering him for adoption. She named him Eli because he was white, which made her think of a cotton ball, which led her to Eli Whitney, the inventor of the cotton gin. She wanted to keep him, but her own dog was jealous.

“He was just another white pit bull as far as I was concerned,” Dr. Bianco later told me. “But he had a charming personality. You have to understand that we get pit bulls in here on a somewhat regular basis. We repair them when we can and try to adopt them out. There’s dogfighting going on in this area. One time a kid brought in a pit bull he said had been attacked. He was crying, and he said he could not afford the surgery. One of my clients, who was in the waiting room when the kid came in, volunteered to pay for it. The surgery cost her eight hundred dollars. Several months later, the kid came back with the dog torn up again. He was clearly fighting the dog. I confronted him. I said to him, ‘You’re fighting this dog.’ He denied it, of course. I told him, ‘Listen, I know you are. I’ll fix him up this time, but don’t bring him back here again.’”

The Pennsylvania SPCA, which is located in Philadelphia, receives anywhere from fifty to seventy-five reports of dogfighting a month. Through the years, I have met fighting dogs that have survived and other rescued dogs that have been abused and mistreated in horrific fashion. But for obvious reasons, survival is exceedingly rare in a dog who has been used as bait and mutilated to the extent that Oogy had been. And it’s even rarer that, after the unspeakable depravity and abuse that had been inflicted upon him, the dog maintained a trusting, loving spirit.

I am routinely overwhelmed by the circumstances that brought Oogy to us. There are so many “ifs” involved: if the fighting dog had killed Oogy as he was supposed to do; if Oogy had not somehow survived his torment; if the police had not raided the facility at the moment they did; if the raid had not been local, so that the police would not have had access to ER services; if Diane and Dr. Bianco and the staff had not been so determined to save Oogy…

Long after Oogy had come to live with us, when I had pieced together as best I could how events had unfolded, I related the story to Noah and Dan, told them how Diane had refused to allow Oogy to be sent to the SPCA, insisted that Dr. Bianco save him, and had essentially dedicated herself to not letting him die.

Noah blurted out, amazed, “Really? That really happened? Diane really did that?” He broke into a wide grin. “Jeez,” he said. “Diane’s a freakin’ saint!”

“Saint Diane!” Dan exclaimed. “I like that.” He rolled it around in his thoughts for a few seconds. “Saint Diane,” he said. He, too, had a broad smile on his face. “The patron saint of hopeless causes.”

t

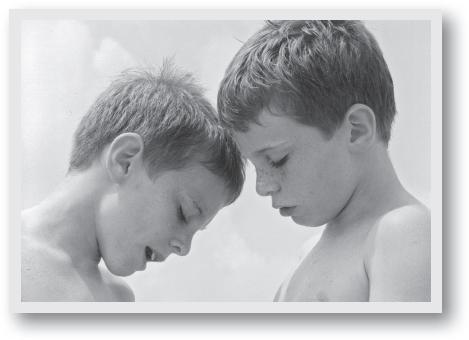

he boys have always known they were adopted. They were three days old when they came into our lives, and we told them the very first day how ecstatic we were with the way events had played out. Even before they could acknowledge it, they were told how they came to be in our house and made it incandescent. It is nothing we ever hid from them. It is part of who they are.

Perhaps this explains why, when the boys were very young, one of their favorite stories was how the pets they shared the house with then, a rescued dog and two rescued cats, came to be in our family. I think that knowing how beloved these animals were, being able to love them on their own, and the story of how all of this came to be reassured them that kindness and caring are neither limited nor determined by the traditional biological parent-child relationship. What matters are the opportunities that are created and the extent to which the offered potential is fulfilled — the chance and ability to give love and support when they are most needed.

I would be flattering myself if I said that I’d been ambivalent about becoming a father. Nothing about parenting had generated any eagerness in me, no doubt as a result of the attenuated relationship I had had with my own parents and the experiences of my own childhood. However, because Jennifer badly wanted to be a mother, I agreed to pursue the choice. We endured multiple miscarriages, faced fertility issues, and ultimately gave up trying to get pregnant. We looked at several adoption agencies, but because I was over forty we did not satisfy their criteria. Ultimately, a friend told us about Golden Cradle, an adoption agency located in south New Jersey that did not consider age a determinative factor in one’s ability to be a good parent. We applied and were accepted into the program.

Arty Elgart had founded Golden Cradle, which is a nonprofit organization, after it took him five years to adopt his first child. Arty had concluded that adoption should not have to be such an arduous experience, and he sought to expedite the process of matching would-be parents with birth parents. After fifteen years on the Golden Cradle board of directors, I have come to the conclusion that what has made traditional Golden Cradle adoptions so successful — those in which the agency finds and assists the birth parent(s) and then arranges for the adoption by parents in the program, who have paid a fee — is that the agency makes certain that an adoption happens for the right reasons. There is no lingering regret by the birth mother or birth parents; they understand that it is in the best interests of the child to place him or her in the hands of another couple. There is no second-guessing; they know the child will be well loved and that they are sharing a gift of inestimable value.

In a traditional adoption, the birth parents pick the parents to whom the child is going to be introduced. When an expectant mother or couple who wanted to place their child for adoption through Golden Cradle contacted the agency, Golden Cradle would focus on what was important to the birth mother or birth parents. The agency would ask, What characteristics do you want to see in the couple who will adopt your child? And if the mother answered, Well, I’m Italian, and I am a potter, so I’d like the child’s parents to be Italian professionals interested in the arts, Golden Cradle would reply, Well, we have an Italian couple who are not professional and are not really interested in the arts, and we have a Jewish professional couple who are. What’s more important to you, religion or lifestyle? Depending upon the responses that Golden Cradle received to the questions posed, it provided prospective adoptive couples’ autobiographies for the birth parents or birth mother to choose from that reflected the birth parents’ interests.

For the first six months after placement had occurred, adoptive parents would prepare what were known as “Sharing Sheets,” letting the birth mother/parents know how the child was developing and the parent-child relationships were evolving. The Sharing Sheets, each of which included at least six photographs, were turned over to Golden Cradle and forwarded to the birth parent(s). Knowing that the child was doing well and was loved and appreciated served to confirm the correctness of the decision and helped the birth parent(s) to say good-bye.

When we joined Golden Cradle, forty couples at a time were accepted into the program, all of whom were waiting for children through traditional adoptions. Arty spoke at the first meeting of our class. And the first thing he said was: “I want you all to relax. You’re all going to be parents. One couple has to be first, and one couple has to be last, but you’re all going to get a baby.”

Early on, Golden Cradle staffers had learned that when they called adoptive parents for administrative reasons and told them, “This is Golden Cradle,” people would flip out, thinking that they had just been placed and were now parents. So at the first meeting everyone was informed that if someone called and said they were from Golden Cradle, it did

not

mean there was a baby waiting for them. When the phone rang and the voice on the other end said, “This is the stork calling,” the baby was there.

Jennifer and I ended up being the last in our class to be placed. It took almost two years. We had been waiting for the call so long, we had stopped thinking about it. Despite the assurances we had received, it seemed a distant possibility, not guaranteed or inevitable. Anticipation about becoming parents had long since faded into the grind of our daily lives. We stopped wondering about and planning for a future centered around kids. As it turned out, twice before we actually were placed, birth mothers had picked us before changing their minds about placing their children. Hence, no “stork call.” But we had no way of knowing that at the time. And as things turned out, it all was for the best.

I was forty-four years old when we got our stork call. In retrospect, I am glad this part of my life came as a complete surprise. If somebody had said to me ahead of time, “You’re going to be the forty-four-year-old father of twins,” I would have said, “There’s no

way

that’s going to happen.” I was riddled with doubts as to my ability to be an effective father. I felt wholly inadequate and unprepared to be the father of one child, let alone two at the same time.

One Saturday morning, Jenny and I were sitting on the couch having coffee, reading the paper, and getting ready to go into center city and put in a few hours at our respective law firms. I had come to believe that some people consume themselves with their jobs and careers so that they do not have the time to examine the emptiness or unhappiness in their lives. I think we were like that. We were both under enormous pressure to perform, and neither of us had the confidence to feel that we were good enough, which kept us working harder, pushing a burden up-slope to a destination we could never reach. We had substituted work for a life of substantive content and meaning. We were simply going through the motions.

And then the telephone rang.

Jennifer and I looked at each other. Neither of us had any idea who might be at the other end of the line. It wasn’t the time of day that the phone rang in our house. My first reaction to phone calls at unexpected hours was that they bore bad news. I stood up, put the section of the newspaper I had been reading on the couch, the coffee cup on the end table. I walked to the bookcase and picked up the receiver.

“Good morning,” I said, trying to sound as positive as I could. I would defy the intruder on the other end of the line.

“Hello, Larry. It’s Susan from Golden Cradle. Guess what? This is your stork call.”

Susan was the social worker we had worked with since enrolling with Golden Cradle. My thoughts immediately went to the night before. Every Friday night for years, a bunch of us from the office had gone out to a bar. I sensed in that moment that I would never again go out drinking with the folks I worked with. I never did.

I felt as if I had been hit in the back of the head with a two-by-four, except that it didn’t hurt. Everything had been knocked out of me. It was our social worker, Susan, telling me that we were parents. What did

that

mean?

Rather stunned, I said the first thing that came into my head: “Really? That’s amazing.” I was buying time, trying to internalize what Susan had just told me.

Susan said, “Congratulations. You and Jen are parents. Would you like to know what you have?”

“Of course,” I said.

“You’ve got a boy,” Susan said. “He’s three days old and he’s absolutely beautiful.”

“No kidding!” I exclaimed. I had the strangest feeling, as though I were speaking under water. “I guess this means,” I said, “that we don’t get to go to the movies tonight, right?”

By now, Jennifer had put down her newspaper and was looking at me, trying to figure out what was going on.

“Wait,” Susan said. “There’s more.”

“There’s more?” I asked. I was in a complete state of shock as it was. “What do you mean, there’s more?”

And Susan said, “Your son has a brother. You’ve got

twins

!”

“Here,” I said, suddenly overwhelmed by this news, and held out the receiver to Jennifer. I realized that everything in my life had abruptly been reprioritized. Concerns I could never have been able to imagine would from now on take precedence and control my days. I recalled, in some remote part of my brain, a conversation I had had with my oldest friend, who found out at forty that she was pregnant with twins. In typical fashion for her, she had researched the parenting experience. She had told me that the studies showed that if you were parenting correctly, you would not have time for many of the things that you thought were important before you became a parent, but you would feel more fulfilled as a result. I’d had no idea what she meant. At the time she told me this, my hobby was photography, and I was working in my darkroom twice a week until 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. I could not imagine giving that up. I have spent a total of two nights in the darkroom since the boys came home, printing up photos as a favor to a friend. I have never once missed it.