One Train Later: A Memoir (45 page)

Read One Train Later: A Memoir Online

Authors: Andy Summers

Tags: #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Guitarists

On the morning before I leave the Yak and Yeti to fly to India I sit in my room, practicing. For some reason I get into improvising on an old Charlie Parker tune, "Scrapple from the Apple." The door is halfway open and the Nepalese cleaning lady passes by. I hear a murmur of approval and then another one as I riff away on my own. Her face appears with a shy smile around the doorway, and it's obvious that she is digging it. I momentarily raise a finger and beckon her in. She enters and I keep on playing over the Parker changes as she sits quietly on the floor and closes her eyes, listening intently. It is akin to playing to a deer in the forest, a tremulous moment when you might easily scare the creature away. I keep playing and think, My God, Parker comes to Katmandu, then she gets up and makes the namaste sign and goes back out into the corridor, presumably to do her work. I pack away the little Gibson acoustic with a smile and think, Is there anything actually better than music?

In Delhi I spend the evening with Mr. Hakim Ghosh, who owns a stall in an underground market. I wandered by in the early evening and got into conversation with him, now he insists on taking me to dinner. We sit in a beautiful restaurant and he talks nonstop about his family, the future of India, and his father, who worked under the British. He has a brother with a family now living in Bethnal Green in London. I tell him that is where my mother was born, and we smile at each other in fraternity as we dip into a bit more prawn marsalsa. We finally part company with promises to write and stay in touch, and then having no other option, I spend the rest of the night in a squalid lodge across the road from the airport, waiting for a flight to London that is scheduled to leave at seven A.M. The room, illuminated by a single bare bulb dangling from the ceiling, is filthy and worn with light-greencolored paint flaking off its walls. I lie on the bed, keeping all my clothes on and my suitcase under my feet. At five A.M. sleepless, I wearily roll off the bed, go outside, and get a taxi to the airport, which is a nightmare scene of bodies lying in heaps everywhere on the floor as if dead. In the insufferable heat I join the interminable line for the flight, praying that I am going to get on. The plane takes off about eight A.M., and I let out a great breath, having made it through all of that.

I arrive back to the creeping cold and grey of Ireland and a partner who by now is alienated. This time it's difficult to get back to where we were; I feel I am straddling two worlds but somehow don't quite take it in, thinking that the estrangement due to the demands of showbiz couldn't possibly happen to us. This new feeling of distance between us is compounded by the bone-numbing damp and quiet of an Irish village-particularly in my head after the glamour and excitement of so many exotic cultures.

Although we now have some friends in the area, I find it hard to settle into any kind of social scene. I have a need-like a drug-to keep the illusion, the constant high, going all the time, but it seems impossible here in this tax-exile life I have returned to. I need to repair the damage I have done to our relationship with my prolonged and self-indulgent absence. But it's difficult to feel good here, where most of the time we are just coping with the cold and the lack of resources or anything to do except wander along the freezing and wild cliffs. It is a sad moment: the intimacy, love, and humor of just two years earlier seem to be slipping away, knocked out by the rush of the new world I am embroiled in.

I try but cannot fit into this scene that consists of going to the pub every night, drinking beer, and playing darts. I laugh and swallow brown ale in a haze of thick tobacco smoke, but I'm choking on the inside. As I raise my hand to chuck a dart at the hoard on the wall, I scream to be in New York or back onstage with a guitar. But I try to trick myself into believing that this is really the life, and in an effort to be like the locals, I go out on a sailing boat one day but feel so sick and hungover that I spend the whole time with my eyes closed on a bunk and Ireland passes through my head in a collage of thick, furrowed dirt, crashing salt water, black rubber boots, and endless pints of strong brown tea. In this village I'm regarded as a rock and roller, with all that the phrase implies.

In an effort to keep the insidious chill out, I dress in thick woolen clothes and leave the rainbow robes of rock and roll in a suitcase, where they lie like flags of a past life. The band begins to feel like a dream I once had, and as I toil with the coal fire and stare numbly at the dying flames, I fail to grasp what is happening to me, fail to see the disintegration of our marriage, cannot grasp what this beautiful woman with our child has sacrificed for me, ignore the widening gap between us, and am inadequate in repairing the damage. To compound this situation, I set up a studio in the basement that has one small window to let in the grey light. It's like a cell and I write songs obsessively for hours on end while my wife and child are elsewhere. Occasionally journalists visit to interview me, and it feels like a reprieve as I regain my persona for a few hours until they leave and I return to my song demos and the gunmetal skies of southwest Ireland.

One afternoon Kate comes into the basement with two-year-old Layla in her arms. There is a nasty gash on the baby's forehead. "Your daughter," she says, and drops her in my arms and then leaves the room. It says everything. I feel gutted. I try to make things better but I am like a man straddling two islands that are drifting apart, and the next two months pass with my feeling like a bright pink doll dropped in a field of grey, the fire of our marriage turning to ash.

Twenty-Three

In contrast to this bleak environment, our fourth album is to be recorded in the month of June 1981 at AIR Studios on the Caribbean island of Montserrat. This is the dream; this is the Beatles-a myth we are happy to embrace. We are sure that we will sell millions of the next album, and recording on a Caribbean island is a luxury we can afford. This time we can relax, take our time, get it right. In fact, we are scheduled for six weeks on the island, which by future standards will seem very short, although we never seem to need more than ten days.

After leaving Kate and Layla in Ireland with what I hope is a soulful departure, I head off to Montserrat by way of New York. I arrive in Manhattan around one A.M. and call Belushi. He screams my name into the phone and wants to hit the town immediately, but having just arrived on a long, arduous flight, I decline and say, "How about tomorrow night?" and pass out. At almost six in the morning there's a rapping on my door and I stagger out of bed to see who the hell it is. It's Belushi, with a big grin on his face. "Okay, man, let's go," he says, and walks over to the dresser and lays out twelve lines of coke and just smiles at me as he rolls a bill. "Okay, whaathefuck," I say, and we bend our heads over enough powder to fell a Peruvian llama and do the lot. Like Speedy Gonzalez and his twin brother, we hit the streets of Manhattan at six A.M. in search of a party. Whooping, yelling, and numb, we whip around to several locations, banging on doors as John calls out names. But there ain't much goin' on and despite the blizzard that's raging in our heads, there's nothing to do and by about nine A.M., feeling very wasted, we give up and John says, "Gotta sleep, man. See you tonight." "Yeah, right," I croak. He disappears and sleeps for three days, by which time I'm in Montserrat.

A funky island without the usual tourist glitz Montserrat has a beauty all its own topped off by a volcano that will eventually render two-thirds of the island uninhabitable. We check into the studio and get assigned our own private bungalows for the duration. The heat and lush, verdant topicality of the island drop you like a stone into a state of grooving relaxation, and within a couple of hours you go native. It feels good and it's hard not to laugh out loud at the fortune of all of this as we slip into a luxurious new life of swimming in the mornings, cruising the island, and gathering in the studio after lunch. The other families are here, but Kate has decided not to come; I feel the shadow of her absence under the bright Caribbean light. As I get to know the island I see with a heavy sense of irony that some of the places have Irish names. One village is even called Kinsale.

One of the first things we have to deal with is the fact that Sting has invited a Canadian keyboard player to join us on this album. Stewart and I are incensed, as nothing has been said to us. I feel adamant about not turning our guitar trio into some overproduced, overlayered band with keyboards. But within a day he turns up, a heavily built guy with an oversize ego to match his bulk. He has bamboozled Sting into flying him down from Canada after Sting did a bit of demo recording with him up in Montreal. He is a good player but he's added something like twelve layers of keyboards and synthesizers to one of Sting's songs, "Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic." It's a difficult situation and it's hard for Stewart and nie to talk Sting out of it, so we go into the studio with the keyboards. But here the intruder signs his own death warrant because he smothers everything we play with dense keyboard parts so that we end up sounding like Yes on a bad day. He compounds the problem by leaning over his synthesizer every few minutes and playing us one of his riffs and exclaiming, "Listen to that-boy, if I heard that, I'd love to have it on my album." It's painful. He lasts three days and then even Sting wearies of him and sends him on his way.

After this little debacle we get down to the business of making a real Police record. We begin the process of working our way into the new record by tentatively playing one another our song demos, a painful and difficult moment because each one of us would like to have all his songs recorded. But Sting doesn't want to sing anything unless he has written it, and most of my songwriting in Ireland comes to nothing. I have some good songs that will not get recorded, and I resent it. I have to deal with my own had feeling and try to come out positive, but I can't help thinking that this time one or two of Sting's songs are not as good as mine. Maybe my writing is too close to his or too Police-like for him to feel comfortable. But in the interest of keeping the ship afloat, I go along with it. Sting remarks to Vic Garbarini, a journalist friend of ours, that "Andy is good, too good maybe," and it hurts. We end up recording some songs that in my mind are filler.

However, "Spirits in the Material World," "Invisible Sun," "Secret Journey," and "Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic" are all standout songs, and we get to work on them. "Magic" is a problem because we use Sting's expensive demo as the actual track; Stewart and I just have to try and fit ourselves into it. Strangely enough and despite the fact that it's a great song, it never sounds like a true Police track to one and after the recording we rarely play it in concert. "Spirits in the Material World" is a great new original song inspired by George Harrison. We argue a bit about this one because again Sting has worked it out on a keyboard and wants it on the instrument he wrote it on. The line under the vocal starts with a beautiful extended minor ninth chord. Sting grumbles that it's a bit tricky for the guitar, but I point out to him that in fact I can play the whole part standing on my head if need be-no problem. But he won't budge and we end up with a sort of generic sound that is a mix of guitar and keyboards. Again, it somewhat lacks the true Police sound. "Demolition Man" is a tough rocker that also puts us though a little bit of a power play. I pull off a ripping solo on the outro of the song that should be played loud and clear, but when it comes to mix time it gets played too low and, much to my chagrin, gets lost. Clearly things are starring to move in a weirder direction and it's becoming a fight to keep up the camaraderie. But despite these internal frictions, the truth that Stewart and I have to acknowledge privately is that without Sting's songwriting talent, it wouldn't happen-and this gives him power over the two of us. On the other hand, where would he be without the two of us? It always comes back to the indivisible sum, and in the allpervasive group life, lines like this become an interior monologue. But in this moment and put crudely, it becomes either Sting's way or no way; almost all ideas are carried out on a confrontational basis, and the idea of a group democracy fades. However, one of my songs does make it onto the album. It's called "Omega Man," and in the end Sting somewhat resentfully agrees to sing it even though it's clear that he doesn't really want to. Later Miles plays it at the first A&M meeting about Ghost in the Machine, and they want to release it as the first single, but Sting puts his foot down and will not let it happen-so it doesn't, When I hear about it, it feels like a knife in the back.

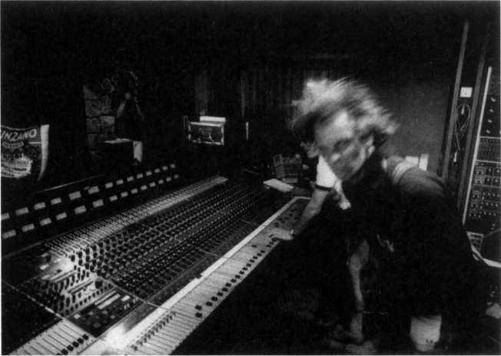

This time the studio feels more like a canvas for dirty fighting. The stakes have been raised.. and instead of rejoicing in the unbelievable success we have created together, we lose sight of the big picture and go on in emotional disorder, each one of us battling for his own territory. In the deeper recesses of our collective soul there is a bond between us, but it's getting veiled by the arm wrestling, the internecine battling and striving, the pushy maleness of it all. There are arguments in the studio in which each one of us wants his instrument slightly louder than the others, wants his songs recorded, will not be less than anyone else. It is a combative process, with the poor engineer trying to arbitrate as three sets of hands fiddle with the faders.