One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (32 page)

Read One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America Online

Authors: Kevin M. Kruse

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Religion, #Politics, #Business, #Sociology, #United States

Ignoringâor perhaps ignorant ofâthe opinion's limits, several of Black's critics warned of a slippery slope ahead. “In a country whose forefathers used the word âGod' in virtually every document written,” worried a woman from San Diego, “suddenly our children might be outraged or contaminated by the very use of His name in a simple petition! Will the next step be forbidding the reading of these same documents in our American history classes? Where will this end?” “What's next?” wondered a rural Alabamian. “Will God's name be omitted from the âFlag Salute' and âStar Spangled Banner' to appease the atheists?” “When do you plan to require our Government to take â

IN GOD WE TRUST

' off our money?” asked a Virginian. For some, dire consequences were limitless. A California man fired off his fears in rapid order: “Next God will be taken out of the oath of the President; out of the courts; out of the National Anthem, the salute to the flag; off of the coin of the U.S.; out of the Battle Hymn of the Republic; prayer will be taken out of the House and Senate; the national observance of a Day of Thanksgiving to God abandoned,” and finally “Christmas and the Christian Sabb[a]th” will be objected and vetoed by our Supreme Court as embarrassing to somebody.” Some imaginations ran even wilder. “How about next time around lets abolish all references to God in official documents,” wrote a woman from Fort Lauderdale. “Then the third time around lets imprison anyone mentioning God or attending a religious service, & fourth time aroundâset up the firing squad, & fifthâget your silver platter out & hand us over to you know who.”

39

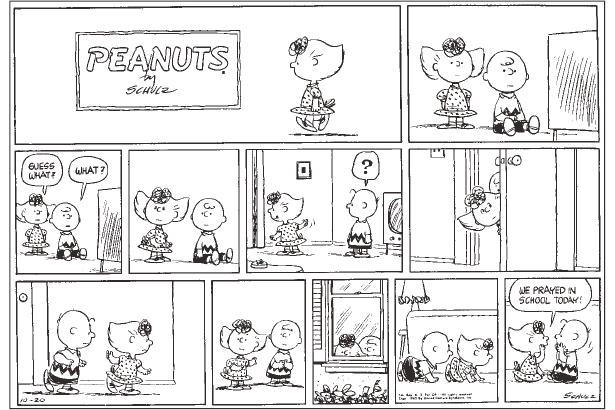

The Supreme Court's decisions striking down state-mandated programs of prayer and Bible reading in public schools generated a wide range of reactions. Here, Charles Schulz captured the popular panic that the decisions would drive religion out of public life.

PEANUTS © 1963 Peanuts Worldwide LLC. Dist. By UNIVERSAL UCLICK. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

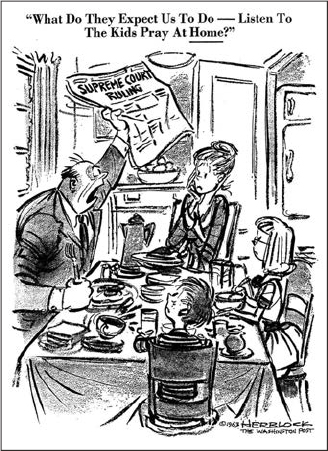

In this image, political cartoonist Herb Block dismissed such concerns, suggesting that religion might be best encouraged in the private sphere.

A 1963 Herblock Cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation.

For Black, the deluge of criticism was stunning. Reading the angry letters, he said, was a “real education.” He replied to the calmer complaints, often suggesting that his correspondents had been misled about the decision and urging them to read it themselves. He largely ignored the angrier ones but occasionally felt compelled to respond. “One woman condemned Hugo to Hell,” his wife recalled, “and he wrote an answer telling her a bit sarcastically, I thought, that if she would go to the library (as he was sure she would not have it in her own house) and ask for a book called the Bible, she should turn to the chapter and read where it said âPray in your own closet.'” Black, the former Sunday school teacher, referred other critics to that same passage, though usually in gentler tones. “To those who think prayer must be recited parrot-like in public places in order to be effective,” he explained to a niece, “the sixth chapter of Matthew, 1 to 19, might be reflected upon, particularly verses 5 through 8.”

40

Black was not the only one who took solace in the Gospel of Matthew. Reverend Edward O. Miller, the liberal rector of St. George's Episcopal Church in Manhattan, applauded the

Engel

ruling in the

Christian Century,

citing the same passage as his rationale. Dean Kelley, a United Methodist minister who led the National Council of Churches' Department of Religious Liberty, parodied the same piece of Scripture to mock the Court's critics. “Practice your piety before men to be seen by them,” he chided. “Require the little children to bow their heads and pray, or at least keep silent while others do, using the pious words that your rulers give you. Then everyone will remark how religious you are. Then religion will be greatly helped and faith in Faith will become very popular.”

41

Initially, these religious supporters of the decision were few in number. Reacting to the early, exaggerated reports of the ruling, most churchmen were aghast. Billy Graham was “shocked and disappointed” by the decision, which he warned was “another step toward secularism in the United States.” “Followed to its logical conclusion,” he said, “prayers cannot be said in Congress, chaplains will be taken from the armed forces,

and the President will not place his hand on the Bible when he takes the oath of office.” Francis Cardinal Spellman, Catholic archbishop of New York, likewise said he was “shocked and frightened” because “the decision strikes at the very heart of the Godly tradition in which America's children have for so long been raised.” Such reactions from conservative religious figures might have been expected, but some liberal clergymen voiced the same complaints. The theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, for instance, defended the Regents' Prayer as “a symbol of the religious life and tradition of the nation” and criticized the Court for “using a meat-ax” against it. Bishop James A. Pike of the Episcopal Church likewise worried that “the decision

deconsecrates

not merely the schools, but the

nation.

It is, as someone has said, âa new Declaration of Independenceâindependence from God.'”

42

In time, however, most religious leaders made peace with the ruling. To Black's delight, Baptist bodies including the Southern Baptist Convention supported it, believing it fit well with their faith's traditional stance on separation of church and state. Jewish leaders welcomed the ruling as a defense of religious minorities' right to worship as they saw fit, an opinion echoed by smaller Christian denominations such as the Quakers. A number of prominent Protestant publications, from the liberal

Christian Century

to the conservative

Christianity Today,

offered support as well. Some Catholic periodicals did too, with one deeming the initial reactions by the church's hierarchy a “hysterical kind of nonsense” that did no good. Upon further review, even some early critics softened their stance. A few weeks after the ruling was handed down, Billy Graham told newsmen he now believed “the particular decision was all right.” When confused Christians wrote for an explanation, his aide had a ready answer. “The Supreme Court has not said that to pray in public schools is unconstitutional,” he explained repeatedly. “The only thing they did was to say that the New York State Board of Regents or any other government agency was not authorized to compose prayers to be said in public institutions. I am sure you do not want the New York State Board of Regents to make up your prayers for you.”

43

In fact, as they examined the details of the case, many religious leaders decided the Regents' Prayer was not much of a prayer after all. Seeking to offend no faith, the New York school officials had actually offended

many. “The prayer sounds like a Boy Scout oath,” scoffed Rabbi Philip Hiat of the Synagogue Council of America. “It's a downgrading prayer.” Dr. Franklin Clark Fry, president of the Lutheran Church in America, agreed. “When the positive content of faith has been bleached out of a prayer,” he said, “I am not too concerned about retaining what is left.” The evangelical editors of

Christianity Today

refused to mourn the demise of a “corporate prayer” that represented little more than a “least-common-denominator type of religion.” The

Christian Beacon,

voice of the far-right fundamentalist American Council of Christian Churches, echoed this argument. “Prayer without the name of Jesus Christ was not a non-denominational prayerâit was simply a pagan prayer,” the editors announced. Reciting it was an empty gesture that would “not get higher than the ceiling anyhow.”

44

These religious leadersâand the millions who took their cues from themâcame to believe that the Supreme Court had not sided against true prayer. They took solace in the opinion's assurances that all the other religious references in public life would remain undisturbed. But more important, they took to heart the idea that the

Engel

ruling had targeted a prayer that came from bureaucrats instead of the Bible. This uneasy truce between the court and the churches, however, would be short-lived.

A

S RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL LEADERS

tried to make sense of the Supreme Court's decision on school prayer in 1962, many warily awaited another ruling on the related matter of Bible reading in the public schools. Devotional readings, generally drawn from the King James Version, had been part of public school curricula in much of the country since the early nineteenth century. By the middle of the twentieth century, the forty-eight states fell neatly into four categories. In twelve states and the District of Columbia, daily readings from the Bible were legally mandated in all public schools. In twelve others, legislation or legal decisions specifically permitted the practice but did not require it. Another thirteen states had never addressed the issue but seemed to permit it. In the last eleven, Bible reading had been explicitly banned from public schools either by state constitutions or by acts of the legislature.

45

Regionally, the bulk of Bible reading took place in the South and Northeast, in 77 percent and

68 percent of school systems, respectively. In the Midwest and West, by contrast, the practice was far less common, with only 18 percent and 11 percent of school districts either mandating or permitting Bible readings.

46

In states that required the practice, public officials oversaw it with precision. In Idaho, for instance, teachers were required each morning to “read, without comment or interpretation, from twelve to twenty verses from the Standard American Version of the Bible, to be selected from a list of passages designated from time to time by the State Board of Education.” School districts were legally obligated to furnish each classroom with a regulation copy of the Bible. The state board, meanwhile, fulfilled its legal duty by providing teachers a carefully prepared list of 452 sets of readings, ranging from seemingly nondenominational topics such as “Prose and Poetry” and “Great Songs and Lyrics” to explicitly Christian topics such as “Life of Jesus” and “Letters” from Paul, James, Peter, and John. Elsewhere, local boards determined the details. In Little Rock, the board of education composed a handbook on “Character and Spiritual Education” in 1954 “with the hope that it will be of help to teachers in conforming to the statutory requirements in the State of Arkansas.” (Among other instructions, the guide reminded administrators that “the motto âIn God We Trust' [had] to be appropriately placed in every classroom.”) On Bible reading, the school board assigned broad themes for each month of the school year and then designated specific passages for each day, with various grade ranges assigned different lessons. For instance, on the first Monday morning in the sixth month of the school calendar, students were taught “Jesus Loves Children (Mark 10:13â14, 16)” in grades 1â3, “The Kingdom of God Is the Message of Jesus (Mark 1:9â15)” in grades 4â6, “Check Yourself First (Matt. 7:1â12)” in junior high, and “The Beatitudes (Matt. 5:1â12)” in senior high.

47

As states and cities such as these mandated Bible reading in public schools, they invited court cases that again testified to a wide range of opinion. By the mid-twentieth century, courts in fourteen states had determined that Bible reading was not a “sectarian practice” and therefore could continue.

48

In Georgia, for instance, a state court asserted in 1921 that “it would require a strained and unreasonable construction to find anything in the ordinance which interferes with the natural and inalienable right to worship God according to the dictates of one's own

conscience.” Courts in five other states, however, came to the opposite conclusion.

49

“It is true this is a Christian state,” an Illinois court noted in 1910. “The great majority of its people adhere to the Christian religion. But the law knows no distinction between the Christian and the Pagan, the Protestant and the Catholic. All are citizens. Their civil rights are precisely equal. The school, like the government, is simply a civil institution. It is secular not religious in its purposes. The truths of the Bible,” it held, “are the truths of religion, which do not come within the province of the public school.”

50

Despite the differing opinions in the states, the Supreme Court never directly addressed the constitutionality of such school programs until the early 1960s.