One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (13 page)

Read One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America Online

Authors: Kevin M. Kruse

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Religion, #Politics, #Business, #Sociology, #United States

A

FEW DAYS BEFORE

C

HRISTMAS

in 1952, Dwight Eisenhower addressed the crowded ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. As reporters hurriedly took notes, the president-elect asserted that “the great struggle of our times is one of spirit” and, therefore, “if we are to be strong, we must be strong first in our spiritual convictions.” With members of his new administration looking on, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Eisenhower explained that Americans “have got to go back to the very fundamentals of all things. And one of them is that we are a religious people. Even those among us who are, in my opinion, so silly as to doubt the existence of an Almighty, are still members of a religious civilization, because the Founding Fathers said it was a religious concept that they were trying to translate into the political world.” In the crucial passage in his speech, Eisenhower called the crowd's attention to the invocation of “the Creator” in the preamble of the Declaration of Independence. He then insisted, in what quickly became a famous line, that “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply-felt religious faith, and I don't care what it is.”

1

That single sentence from Eisenhower, more than any other during the campaign or perhaps even his presidency, resonated with observers across the political spectrum.

2

For William Lee Miller, a liberal theologian at Yale Divinity, Eisenhower's reference to a “deeply-felt religious faith”âa phrase to which he would repeatedly return as presidentâsignaled an immaturity in his thinking. “Depth of feeling is the important thing, rather

than any objective meaning,” Miller wrote. “One might say that President Eisenhower, like many Americans, is a very fervent believer in a very vague religion.” Other critics agreed. “Is this not just another indication that in America religion is considered vaguely to be a good thing,” the sociologist Robert Bellah asked, “but that people care so little about it that it has lost any content whatsoever?” Conservative scholars, however, believed that liberals entirely missed the point. Though he shared their concerns about the shallowness of Americans' civil religion, the sociologist Will Herberg appreciated its essential power and effectiveness. “The President was saying something that almost any American could understand and approve,” he noted. “Eisenhower's apparent indifferentism (âand I don't care what it is') was not indifferentism at all, but the expression that at bottom the âthree great faiths' [Judaism, Catholicism, and Protestantism] were really âsaying the same thing' in affirming the âspiritual ideals' and âmoral values' of the American Way of Life.”

3

Indeed, for Eisenhower, the most important thing about religion was its power to unite Americans around a common understanding of their past and to dedicate them to a common plan for their future. While critics mocked the president for being “a very fervent believer in a very vague religion,” that was exactly his intent. He understood that, in a diverse nation long divided along doctrinal lines, religion could serve a public role only if it was reduced to its lowest common denominatorâor, perhaps, its lowest common denomination. In this respect, the president was perfectly matched to the moment. On the surface, the postwar period witnessed a tremendous revival in religious faith that clearly distinguished that era from the past. The percentage of Americans who claimed membership in a church had remained fairly constant in the early twentieth century, barely rising from 43 percent in 1910 to 49 percent in 1940. The decade and a half after the Second World War, however, saw a significant surge: the percentage claiming a church membership climbed to 57 percent in 1950 and then spiked to an all-time high of 69 percent at the end of the decade. Even though studies revealed the revival to be a bit light on substanceâa Gallup Poll in 1950, for instance, found that while 80 percent of Americans believed the Bible was “the revealed word of God,” only 47 percent could name even a single author of the gospelsâthe shift was nonetheless remarkable. The American people, like Eisenhower, had become very fervent believers in a very vague religion.

4

While this broader picture helps contextualize Eisenhower's call for a “deeply felt religious faith,” the specific setting for his remarks is even more revealing. The gathering at the Waldorf-Astoria in late 1952 was the annual meeting of the board of the Freedoms Foundation. “These days I seem to have no trouble filling my calendar,” the president-elect told them. “But this is one engagement that I requested. I wanted to come and do my best to tell those people who are my friends, who are supporters of the idea that is represented in the foundation, how deeply I believe that they are serving America.” The basic idea of the Freedoms Foundation was that those who promoted “a better understanding of the American way of life” should be singled out for awards and attention, especially those who celebrated the central role played by “the American free enterprise system” in making the nation great. Fittingly, for an organization devoted to the promotion of big business, its president was Don Belding, head of a national advertising agency whose clients included Walt Disney and Howard Hughes. The board of directors, meanwhile, included leaders at General Foods, Maytag, Republic Steel, Sherwin Williams, Union Carbide and Carbon, and US Rubber, as well as individuals such as Sid Richardson and Mrs. J. Howard Pew. The corporate presence was so pronounced that one honoree sent his award back, grumbling that the Freedoms Foundation was “just another group promoting the propaganda of the National Association of Manufacturers.”

5

More accurately, the Freedoms Foundation promoted Christian libertarianism. Belding was a close ally of James Fifield, whom he personally praised as “Freedom's Crusader” in a ceremony honoring the minister in 1950. The advertising executive was deeply involved in the work of Spiritual Mobilization, regularly attending events in Los Angeles and serving as a founding member of the Committee to Proclaim Liberty. Many members of the Freedoms Foundation board, including E. F. Hutton, Fred Maytag II, and Charles White, were likewise active in the same movements. Not surprisingly, the foundation these men created looked favorably upon those groups. Early recipients of Freedoms Foundation awards included Fifield, several regular contributors to

Faith and Freedom,

producers of

The Freedom Story

radio program, and, notably, all the members of the Committee to Proclaim Liberty, who were honored as a group and, in several instances, honored once again as individuals. Presiding over the first awards ceremony in 1949, Eisenhower told the winners they had

“become marked as among America's disciples. You have issued your defiance to all who would destroy the American dream.”

6

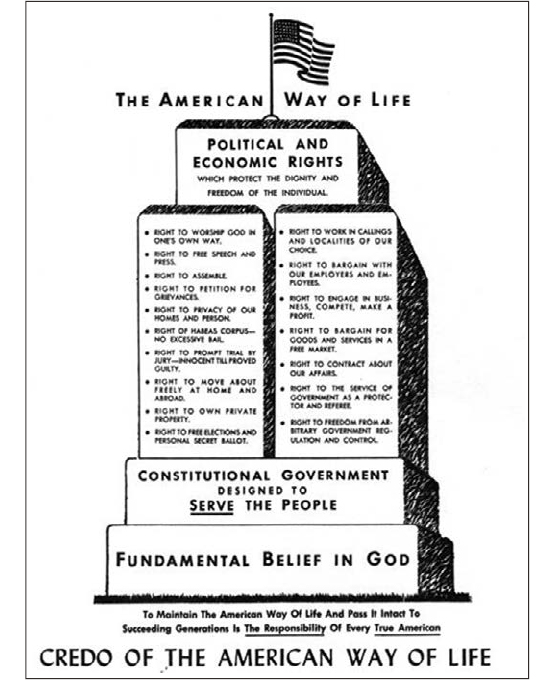

Eisenhower's relationship with the Freedoms Foundation ran back to its founding. In his first meeting with Belding in September 1948, he discovered that the ad man shared his belief that the free enterprise system was in desperate need of defense. “We thoroughly agreed that it is absolutely essential to the security of this country in the years ahead that a coordinated effort, well organized, well disciplined, and well staffed, be created to intelligently direct the education of the American people,” Belding wrote soon after. “It must present the basic principles of our economy, the advantages of the American system, and the dangers inherent in the lack of unity of the American people.” The Freedoms Foundation was the result. Belding led the organization, but Eisenhower established its mission by joining with Herbert Hoover to write its charter. In March 1949, “The Credo of the American Way of Life” appeared in the pages of

Reader's Digest.

It was depicted as a soaring monument whose upper reaches included references to the Bill of Rights and an equal number of rights especially designed for business, including the “right to own private property,” the “right to engage in business, compete, make a profit,” the “right to bargain for goods and services in a free market,” the “right to contract about our affairs,” and, last but not least, the “right to freedom from arbitrary government regulation and control.” Together, these political and economic rights rested on a pedestal inscribed “Constitutional Government designed to

Serve

the People.” And that, in turn, stood on a more substantial foundation: “Fundamental Belief in God.”

7

For the Freedoms Foundation, “The Credo of the American Way of Life” was more than a list of political and economic rights. It was rather, as its name indicated, a

creed

âa statement of religious belief and commitment to a sanctified cause. When Eisenhower launched his “crusade” for the White House in 1952, he pointedly made the credo part of his campaign. For starters, the Republican nominee led a drive to have a monument in its likeness erected in the nation's capital, to honor the American ideal of “permitting the creative spirit of man made in the image of his Maker to reach its highest aspirations, to seek its own destiny, and to serve in the cause of freedom for its fellow man.” While the credo monument never materialized, its message was spread widely in a massive get-out-the-vote campaign coordinated by the Freedoms Foundation

and the Boy Scouts of America. Together, the two organizations put up a million posters in store windows and plastered another ninety thousand cards on trains and buses. On November 1, 1952, the Saturday before the election, they placed more than thirty million additional pieces of literature on doorknobs across the country. Shaped like the Liberty Bell, the door hangers featured the image of the credo on one side and a plea from earnest-looking Scouts to “

Think

when you

Vote

” on the other.

8

“The Credo of the American Way of Life,” designed by Dwight Eisenhower and Herbert Hoover for the pro-business Freedoms Foundation, illustrated their belief that all political and economic rights in America rested on a “fundamental belief in God.”

Courtesy of Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge.

Eisenhower's appearance before the Freedoms Foundation in December 1952 thus served as a chance to thank those who had stood by him

in the election and to promise that his administration would stand by its credo. The businessmen assembled at the Waldorf-Astoria already knew that the president-elect agreed with their goals, and now they heard him embrace their means as well. Whether he ever linked the means with the ends as explicitly as men such as Fifield, Vereide, or Graham did was ultimately irrelevant, for the members of the Freedoms Foundation believed that the latter would naturally follow the former. What was truly important was the simple fact that Eisenhower vowed to take the vague religion of the late 1940s and early 1950s and make it a concrete fixture in the federal government. But this apparent triumph of the Christian libertarians would involve a significant transformation of their arguments. After Eisenhower, religion would no longer be used to tear down the central state but instead to prop it up. Piety and patriotism became one and the same, love of God and love of country conflated to the core.

T

HE RELIGIOUS THEMES THAT

E

ISENHOWER

highlighted throughout the transition period and his inauguration ceremonies were repeated throughout the early weeks of the administration. On Sunday, February 1, 1953, he became the first president ever to be baptized while in office. Despite his upbringing, the president had remained uncommitted to any single denomination for most of his adult life. During the campaign, he had explained the rationale for his rootlessness to his friend Cliff Roberts, an investment banker and chairman of Augusta National Golf Club. “While I have no objection whatsoever to belonging to a particular group,” he wrote, “the fact remains that the only reason for doing so from my viewpoint is the ease it provides in answering questions. It is much easier to say, âI am a Presbyterian' than to say âI am a Christian but I do not belong to any denomination.'” But Eisenhower soon decided he had little choice in the matter. Billy Graham urged him to choose a denomination, if only for appearances. “Frankly,” the preacher warned, “I don't think the American people would be happy with a president who didn't belong to any church.” Eisenhower agreed but said he would wait until after the election, to avoid seeming “to use the church politically.” The denomination he would pick was almost an afterthought. “I suppose Presbyterian,” he said offhandedly, “because Mamie is Presbyterian.” And so, a week and

a half after his inauguration, President Eisenhower was baptized at the National Presbyterian Church in Washington.

9