One More River (31 page)

They were married the next year. Everything went well between them until the day Aurora Mae showed up at Rachel Marie’s birthday party. She’d been abandoned by Bailey, who’d run off with all her money and a young chippie born and bred in Orange Mound, and just when she’d taken charge of Cousin Mags’s orphaned girl and her husband, promising them jobs she could not now provide.

Bernard staked her for a new start and hired Sara Kate and Roland on the spot. He wanted to do more. If he could, he would have kept Aurora Mae in Guilford, supported her and loved her from a distance, the way he was used to doing all his life, but she was having none of that.

You have your family to think of, she said. Three girls and a baby boy! Take care of them the best you can, and don’t let what happened to me happen to none of them or theirs.

He took her words to heart. He put it about he was traveling to Memphis to confer with his family on business and went to New Orleans as usual. He visited his bank and transferred the usual amount of gold coin from a safety deposit box to his cash account for distribution over time by Joshua Stone, who sent him money as he required it. He took the rest of his gold and divided it into two piles. One pile he left in a deposit box, the other he packed in the false compartment of his car. When he got home, he buried it on a dark moonless night in his own backyard. He told no one, not even his wife, Beadie, it was there. One day, he dreamed, when their children were old enough, getting married perhaps or graduating college, he’d produce it and stun them all. Until then, he didn’t want them feeling too at ease in the world or they might grow up like Bernard the handsome, spoiled and cruel. When the war came, he thought about digging up the gold or telling Beadie where it was, but that felt wrong, like he was extending a branch across the Mississippi for the ghost of Bernard the handsome to hop upon and curse his family in his absence. He decided to leave for war with his secret intact, refusing to entertain the idea he might die in battle. If the great river couldn’t kill me, he thought, a Nazi can’t do it, either.

Before he left New Orleans, he had Joshua Stone draw him up a trust that would husband the remaining half of his treasure for the future of his children’s children as a safeguard. He named Aurora Mae and Bald Horace trustees.

Joshua Stone returned wounded from his war in Burma to discover that Bernard died in the Ardennes. Right away, he contacted Aurora Mae and Bald Horace to give them instructions. When the grandbabies come, he told them, you are to telegraph me two code words, and I will contact Bernard’s children for birth certificates and such and release the grandbaby gold to their care accordingly.

What are the code words? Aurora Mae and Bald Horace asked.

Ghost Tree, Joshua Stone said, letting the words sink in as he knew their significance to those two. Then he repeated them. Ghost Tree.

It was twenty years gone before the code was needed. By then, Bald Horace had lost his mind. That left Aurora Mae to see Bernard’s wishes carried out, a duty she held solemn and sacred. The Levy girls had been barren, which meant that the child of Laura Anne Levy, the sole grandchild of Bernard, was a lucky child in some respects long before he was conceived let alone born.

Nah Trang, Vietnam, 1965

T

HE DAY AFTER

C

RACKAH

M

ICK

was wounded, the battle of Chu Lai came around howling like a pack of bad dogs full of long teeth and rabies. Forty-six dead and two hundred wounded and Field Hospital 8 was the only place they had to go. The bunkers were stuffed with mangled and dying men. The docs were in high-gear triage. They put the stabilized, Crackah Mick among them, outside in the grass under tarp on poles in case the rains started and left them to speculate on what came next.

He spent his week at Nah Trang trying to comprehend what had happened to him and always came up empty. He knew his legs didn’t work, although one of them seemed to twitch now and again, and both of them hurt like hell sometimes, especially when he tried to sleep with or without the drugs. They sure wouldn’t do anything he told them to. He didn’t know if this was because they were healing and needed time or if it was because they were gone for good and would never come back. He grabbed the coattails of his doc, a Lieutenant Stein out of New York, as Lieutenant Stein was rushing past his cot and asked.

The doc said, What do I look like, a neurosurgeon? Hope for the best, son. You’ll find out when you get back home.

Mickey Moe didn’t believe he was going home. He didn’t see anybody in a hurry to ship him there. He saw other boys go off to general hospitals in country or in the Philippines and Japan. Some of them went directly home. It was as if they’d forgotten him with all the commotion going on. For all he knew, they’d keep him there in Field Hospital 8 until his tour was over. Certainly, he did not seem to be anyone’s priority.

For days, helicopters dropped off the wounded. Orderlies lined up corpses in bags near the makeshift tents of the stabilized. After a couple of days, they started to transport the bags to an amphibian hospital from which they’d be flown back home to their families and Arlington. Mickey Moe thought about crawling inside a bag himself. At least it would get him out of Field Hospital 8.

The only good part about waiting was they let him call home. He called twice. The first time, his mama fainted dead away at the sound of his voice. The second time, he reached Laura Anne before the first ring was over. She told him she loved him, and he told her he loved her. He asked for the baby. She told him the baby was fine and dandy and must be a boy, because he kept her up all night hopping around in her belly. Her words made him moan, which made them both teary. Oh Lord, they swore, I miss you so!

He told her he’d been wounded and that he’d soon be home, he couldn’t exactly say when, but maybe she knew something from the Army, what had they told her?

They didn’t tell me a thing, Laura Anne said. All I know is there’s been some fierce kind of bloodbath goin’ on out there. I’ve been tryin’ to figure out where your hill is exactly and how close your unit is to all the fire, but I still don’t really know.

I’m sorry, sweetheart. You have no idea how screwed up the Army is until you’ve been in it awhile. This doesn’t surprise me. I’m sorry if my call has shocked you and Mama.

She laughed in a short, sharp way that brought to mind how strong she was. At the sound of it, he felt proud as a Spartan warrior of his Spartan wife and his heart warmed.

It didn’t shock me at all. I knew something had happened to you. I been a wreck wondering what. Where are you hurt, darlin’? How bad is it? Oh, I know it must be bad if they’re not just patchin’ you up and sendin’ you back in. Please tell me. I can take it.

What about the baby, can the baby take it?

It was a dark and dreadful joke that he regretted as soon as it left his lips. He heard her draw in a breath. There was a piece of quiet between them that would have split open with a kiss or a tender glance if they’d been together. But they were not.

The baby is ours, she said at last. The baby can take it.

So he told her about his legs, how maybe he could use them again and maybe he couldn’t. That they’d best anticipate a long, hard haul ahead. There was another piece of quiet, only this one felt long and jagged and not even the sweetest embrace would shatter it. This quiet needed something hard, exceedingly hard, to break.

Then Laura Anne said, We’ll do what we have to, Mickey Moe Levy. Don’t you worry about it. Everything’s going to be alright. You know how I knew something happened to you? I had a dream about a week ago. I was at the edge of the backwoods up there by Littlefield, and I was dressed in these black pajamas. And you were there, in your uniform, lookin’ so smart and handsome. I pointed into the woods. You followed my direction. You went into the brush. I couldn’t see you anymore. There was a riot of noise. There was fire, there was smoke, and I was terrified, terrified you wouldn’t come back. But you did. Upright on two legs. I swear to God, Mickey. This is the truth. And I just know it means that no matter what, everything’s going to be alright.

He didn’t tell her about his own dream, the one with herself in black pajamas and the severed foot in the jungle, but he’d bet dollars to

pho ga

that she’d had her dream the very same night he’d had his. This seemed more than a coincidence. It felt prescient. He decided to go with her assessment. At the end of the day, didn’t a man and his woman know more than Lieutenant Stein and a boatload of neurosurgeons about their own dang lives?

You’re right, he said. Everything’s going to be fine.

And when they got off the phone, he lay back on his cot under the tarp across from the row of body bags to consider amid the echo of far-off gunfire and the stench of death the wonder that was love.

I

WOULD NOT HAVE WRITTEN

One More River

were it not for my husband, Stephen K. Glickman, a voracious reader with a mind that is always percolating with something new. He took an interest in the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and infused me with his enthusiasm. The tragedy of that spectacular event, the greatest natural disaster in American history, expanded my literary themes of the Southern Jewish Experience and American racism in a way I could not have anticipated, as it came to focus on the mysteries of love and friendship in the face of extreme adversity. So my first piece of gratitude goes to him, who has never bored me, not for an instant of our thirty-nine years to date.

I must also rush to thank my agent, Peter Riva, who counseled me so wisely before presenting this novel to my publisher. I might yet be struggling in a “what the hell comes next” moment without his advice. And of course, I must thank my editor, Diane Reverand, who parries my pouting protests with grace and never gloats when I give in to her wisdom. Thank you, Peter and Diane, thank you.

But I would not be thanking any of the above if it were not for Open Road Integrated Media. For their expertise in shepherding my two novels across all media, I am deeply indebted to Jane Friedman, Jeff Sharp, Brendan Cahill, Luke Parker Bowles, Rachel Chou, Danny Monico, Greg Gordon, Andrea Colvin, Nicole Passage, Laura De Silva, Ann Weinstock, Jason Gabbert, and Lisa Weinert. Their support of both my first novel,

Home in the Morning

, and now

One More River

, has been phenomenal, their energies on my behalf boundless. In today’s publishing world, when so much is expected of authors that is not writing but working in entirely different disciplines, for which we are often poorly prepared, the genius and commitment of these brilliant teammates are priceless.

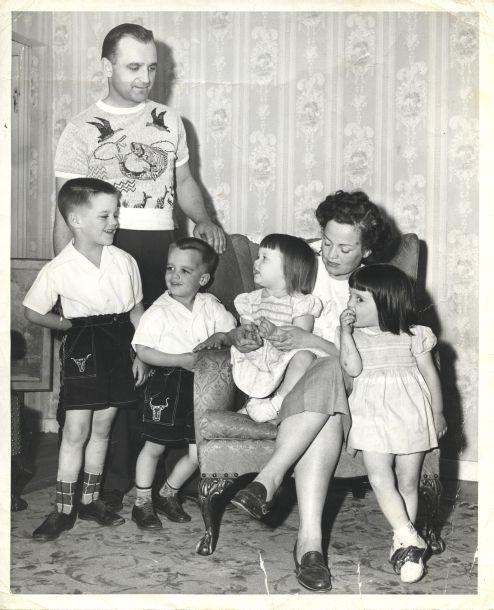

Born Mary Kowalski on the south shore of Boston, Massachusetts, Mary Glickman grew up the fourth of seven children in a traditional Irish-Polish Catholic family. Her father had been a pilot in the Army Air Force and later flew for Delta Air Lines. From an early age, Mary was fascinated by faith. Though she attended Catholic school and as a child wanted to become a nun, her attention eventually turned to the Old Testament and she began what would become a lifelong relationship with Jewish culture. “Joseph Campbell said that religion is the poetry that speaks to a man’s soul,” Mary has said, “and Judaism was my soul’s symphony.”

In her twenties, Mary traveled in Europe and explored her passion for writing, composing short stories and poetry. Returning to the United States, she met her future husband, Stephen, a lawyer, and with his encouragement began to consider writing as a career. She enrolled in the Masters in Creative Writing program at Boston University, under the poet George Starbuck, who encouraged her to focus on fiction writing. While taking an MFA class with the late Ivan Gold, Mary completed her first novel,

Drones

, which received a finalist award from the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities but was never published.

Mary also began a career as a freelance writer working with nonprofit organizations on projects ranging from a fund-raising campaign for the Hebrew Rehabilitation Center to an instructional video for the National Scoliosis Foundation’s screening project. Mary and Stephen married in 1978. Mary made a full conversion to Judaism and later worked as treasurer/secretary for her synagogue.

The origins of her love for all things Southern arose from a sabbatical year. In 1987, Mary and Stephen first traveled to the south of Spain, soaking in the life of a fishing village called La Cala. After seven months abroad and, hoping to extend their time away, they sought a warm—and more affordable—locale. The romance of Charleston, South Carolina, its Spanish moss, antebellum architecture, and rich cultural life beckoned.

Settling into a rented house on Seabrook Island, Mary fell in love with the people, language, and rural beauty of her new home. Following a lifelong desire to ride horses, Mary took a position mucking the stalls at the local equestrian center and embraced riding, finding her match in an Appaloosa named King of Harts. The sabbatical ended and the couple returned to life in Boston, but the passion for Southern culture remained with them. They were able to return permanently to Seabrook Island in 2008, where they currently reside with their cat and an elderly King of Harts.

In 2010, Mary’s debut novel,

Home in the Morning

, was published to critical acclaim, quickly becoming an electronic bestseller. Director/producer Jim Kohlberg optioned the book later that year, with Jeff Sharp of Open Road Integrated Media to produce the film and Peter Riva to serve as executive producer.

Home in the Morning

will be Open Road’s first original ebook to be adapted for film.