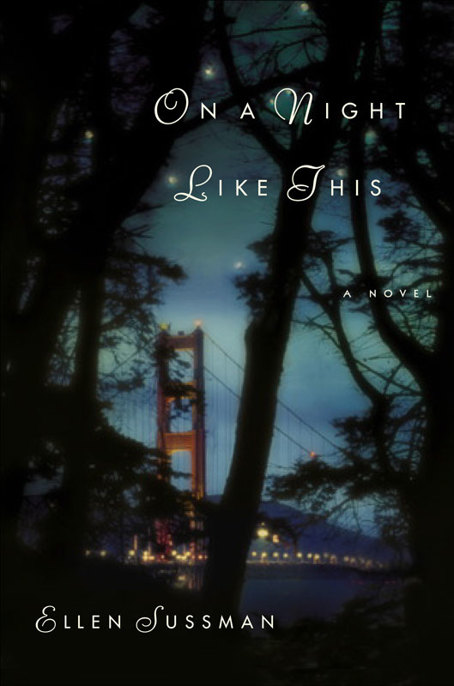

On a Night Like This

Read On a Night Like This Online

Authors: Ellen Sussman

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, except for Sweetpea, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2004 by Ellen Sussman

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group, USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

HachetteBookGroupUSA.com

.

First eBook Edition: January 2004

ISBN: 978-0-446-50600-7

Contents

This novel is dedicated to Neal

and to my daughters, Gillian and Sophie,

with love.

I would like to thank Jonathan Strong and John Barth, my gifted teachers.

Some brave friends read early drafts of the novel, and for their patience and encouragement I thank Susan Goodman, Ken Sonenclar (a writer’s dream of a friend), Kimberly and Les Standiford, and Jeanne Duprau.

Thanks to Dr. Bruce Wintroub for sharing his knowledge of melanoma.

Over the years my many writing students have inspired and challenged me. Thank you all.

I am extraordinarily lucky to have found a terrific agent and a brilliant editor. Thanks to Elyse Cheney and Jamie Raab.

And thank you, Neal, for everything you have taught me about love.

B

lair lifted the man’s arm and slid out from under him. She tucked a pillow back in her place, and he embraced it easily. She smiled at that. Men. She gathered her clothes from the floor and tucked them under her arm, picked up her shoes, stopped in the doorway. She looked back at the man, his long, lean body curled away from her, his hair a tousled mess, his face half buried in the pillow.

I could climb back into bed and stay there awhile,

she thought. She closed the door quietly behind her.

The hallway of his apartment was dark and she slid her hand along the wall until she found a light switch, flicked it on, squinted in the sudden brightness. She hadn’t looked at the clock. Had she slept all night or only an hour or two?

She headed down the hall, drowsily dropped a shoe, which thudded on the hardwood floor. Another door opened and a woman appeared, pajamaed and sleep-rumpled. Blair recovered her shoe, stood and shrugged, naked, too slow to cover herself up.

“Are you a roommate or a wife?” Blair asked.

The woman peered at Blair. Someone without her glasses. “Roommate,” she mumbled.

“Good,” Blair said. “Go back to sleep. I’m leaving.”

“Where’s Perry?”

Perry. That was his name.

“Sleeping. Sorry I woke you.”

The woman plunged back into the darkness of her room. Blair continued on down the hall.

She found the kitchen, dropped her clothes and shoes on the old pine table, grabbed a glass and poured herself water from the tap. She drank, then opened the fridge. Filled the glass with white wine, sipped at it, took it with her back to the table. Microwave clock read 11:45. She had barely slept. Amanda would still be awake, maybe waiting for her. She found a phone, curled into a chair at the table, dialed and drank.

“Hey,” Amanda said into the phone.

“I’m sorry,” Blair told her. “I’m late.”

“Or early,” Amanda told her. “I thought maybe you’d crawl in sometime tomorrow.”

“I don’t crawl, Amanda.”

“Then you’d tango home. Who’s the guy?”

“Maybe I’m at the library. Studying for a master’s degree in quantum mechanics.”

“You coming home?”

“Did you get worried? Damn, I should have called.”

“I didn’t get worried. I’m not a baby.”

“What did you eat for dinner?”

“I finished the lasagna.”

“Damn you. I’ve been dreaming about that lasagna.”

“I’ll make you some eggs.”

“You go to sleep.”

“I’m not tired.”

Blair smiled. “OK, then I’d love a mushroom omelette. With cheese. Tons of cheese.”

She hung up the phone, took one last swig of wine, pulled herself up and out of the chair. When she half-turned, pulling her sweater over her head, she saw someone standing in the doorway.

“You scared me,” she said. Perry. Naked and watching her. She reached for her jeans, pulled them on. Stuffed her bra and underpants into her backpack.

“Who was that? Your boyfriend?”

Blair smiled, shook her head. “My daughter,” she said. “Sixteen years old. Waiting for her mom to come home and tuck her in.”

“You’re some teenager’s mom?”

“That I am.” She slipped her feet into her shoes and turned toward him.

“You can’t stay?” he asked.

“I don’t stay,” she said. “Something you should know about me.”

“Too bad,” he said, covering her hand with his own.

Blair put her hand on his chest, pressed her palm into him. “But I had fun. Tell me where we are. How I get home. That sort of thing.”

They had met at a bar. He had driven them back to his place. She hadn’t paid attention to anything except his slow voice, his hand on her thigh, the soft blur of streetlights from her tequila high.

“I’ll drive you,” he said.

“No,” she told him. “I’ll find a cab. Go on back to sleep.”

“That’s it?” he asked.

“You mean, are we now formally engaged? I don’t think so.”

He smiled. “I mean, can we try this one more time?”

“Maybe. Give me your phone number.”

“You don’t give out yours?”

“Smart man.”

He walked to the kitchen counter, pulled out a drawer, rifled through, found a business card, which he passed to her. He was comfortable being naked—she liked watching him.

“I’ll call you,” she said.

“Maybe,” he told her, smiling.

She pulled her backpack onto her back, headed toward the door. She looked back at him, blew him a kiss. He was watching her.

“Do you always do this?” he asked.

She stopped, leaned back against the door, suddenly tired. She waited.

“Is this what men do? And you do it better?”

“No,” she said.

“Been burned too many times?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

“I give up.”

“I’m dying,” she told him. “It’s easier this way.”

Neither spoke for a moment. It was the first time she said it. Something in her chest tightened. Blair leaned over, placed his business card on the side table by the front door.

“AIDS?” he asked, and she could imagine his mind flashing:

Condom, we used a condom, hallelujah for condoms.

She shook her head. “I wouldn’t do that to you,” she said. “Just cancer. Nothing to be scared of.”

“Except relationships,” he told her.

“Right,” she said. “Everyone’s a therapist these days. Gotta run. It’s been grand.”

She opened the door, walked out, pulled it closed behind her.

Blair caught the last bus to the Haight, walked a couple of blocks, turned down her street. On the edge of the Haight, on the edge of a park, on the edge of elegance. She lived in a rented cottage behind a mansion. A dilapidated mansion in the middle of finely refurbished Victorians, most graced with pastel colors, hers boasting a loud, honking purple. The neighbors hated it. Of course. Which was Casey’s plan.

Casey sat on his front steps, smoking a joint at midnight. She wasn’t surprised. Her landlord had inherited money and the mansion; he coasted through life, women and drugs. She put up with him because she loved the cottage.

“Come join me,” he called out before she turned down the driveway toward her haven.

“Gotta go. Amanda’s waiting.”

“One hit,” he urged. “You’ll sleep better.”

Couldn’t argue with that. Blair walked down the path to the front patio, joined him, midstep.

“Where were you?” he asked, passing the joint.

“None of your business,” she said, taking in a good, long hit of the pot.

“Sex,” he said. “I can smell it.”

“You’re disgusting,” she told him. She took another hit.

Blair looked through the darkness toward her cottage, her daughter inside, making omelettes. She stood. “I gotta go. Amanda’s making me an omelette.”

“Can I join you? I’ll bring wine.”

“No.” She started off, across the ruined grass of the front yard.

“Are you sick?” Casey called out.

Blair stopped, turned around.

“How’d you know?”

“I don’t know. A hunch. Maybe that’s the smell.”

“You’re smart for a rich kid.”

“What’s wrong, Blair?”

“I’m going to die?” she said. But somehow it came out as a question this time. How do you answer a question like that? She shook her head—it still sounded as if the words had been formed in someone else’s mouth. “Thanks for the smoke.”

She turned and headed back behind the house, following a string of white Christmas lights that she used to line the path from the driveway to her cottage, tucked in the far corner of the backyard. The cottage was really a tiny apartment over a garage, but it was built in 1910, all in pine—walls, floors, ceiling—and was graced by a tree that hung over and around the house, making it feel more tree house than garage.

“I’m sick,” she muttered to herself, trying a different take.

No. That’s beside the point. I’m dying is the point.

“I’m dying” is what she needed to tell her daughter.

She climbed the wooden stairs to the cottage and caught the pungent smell of sautéed onion and garlic, saw Amanda’s willowy shadow against the white curtain in the tiny kitchen, heard the African-drumming CD that Amanda listened to late at night with the lights dimmed low; she paused for a moment before turning the doorknob.

Not yet,

she thought.

Not tonight.

She pushed the door open, breathed in, smiled. The small pine-walled living room was tented with lilac-dyed muslin billowing from the ceiling—Blair always felt like she was entering her own exotic harem.

“Amanda, my sweet girl!” she called.

Amanda appeared in the doorway, boxer shorts, cotton camisole, untamed red curls, beaming. “You better be hungry.”

“Ravenous.”

Blair dropped her bag on the floor, beelined for her daughter. She ruffled her hair, planted a kiss on her ear.

“You got taller,” she said, looking her kid straight in the eye.

“Since this morning?”

“Yeah. I think you beat me. Finally.”

“Turn around.”

They turned back-to-back, butt-to-butt, head-to-head. Exactly the same height. But Amanda was fair-skinned and her mother dark, and Amanda’s body was narrower, her bones sharper. She looked like she was about a minute away from becoming a woman, having shed her child’s body only seconds before.

“You didn’t sneak past me,” Blair said, patting their heads together. “Yet.”

They moved toward the table, a battered wood schoolteacher’s desk, which sat in the middle of the tiny room that served as their dining room. Blair dropped, exhausted, into one of the wooden chairs.

“I’ll get dinner,” Amanda said. There was barely room in the kitchen for both of them.

Blair watched her daughter. She somehow felt she could see Amanda in all her incarnations—she was the joyous five-year-old, the headstrong eight-year-old, the surly twelve-year-old, and now this, the lovely young woman—in a flash of an eye. Even now, with a tattoo peeking above her tank top, she was Blair’s baby. A few months ago, Amanda had come home with

rove

tattooed on her chest, just below her collarbone. Blair used to think she knew her daughter completely, knew every expression, every gesture. Rove? What did it mean? Was this Amanda’s first hint of mystery?

“My boss said I can work an extra night at the café if I want to,” Amanda said.

“You want more work?” Blair asked. “Why?”

“I want the money.”

“You don’t need the money. When was the last time you bought new clothes?”

Amanda owned two pairs of jeans—one red and the other lime green—and an odd assortment of bowling shirts, Hawaiian shirts, tuxedo shirts—whatever she found at the vintage clothing store down the street. She looked like a kid playing dress-up, the clothes always too big for her, bound around her waist by bejeweled belts. She looked like no other kid at her high school, and Blair was proud of her for it.

“I buy CDs,” Amanda said.

And help pay the rent,

Blair thought. She grabbed her daughter’s hand as she passed by and pulled her close.

“You’re too grown up, my girl,” Blair said.

“I like working there,” Amanda said. “And when it’s quiet, I can get my homework done.”

“How about parties, friends, goofing off?” Blair asked while Amanda set the table.

“Yeah, right,” Amanda said.

“Is it my fault?” Blair asked. “If I didn’t love you so much, you’d go have fun somewhere else.”

Amanda leaned over and placed her fingers on her mother’s lips. “Stop worrying about me,” she told her.

“Could you bring me a glass of wine, sweetheart?”

The wine appeared, already poured and waiting. Blair took it from Amanda and grinned. When Amanda turned back into the kitchen, Blair closed her eyes, squeezing them tight. Not pain. Just too much noise in her head.

“Do you eat lunch by yourself at school?” Blair asked.

“Why?”

“I’m curious. I hated lunch at school. It was the most miserable time.”

“I read a book,” Amanda said quietly. “It doesn’t matter.”

“It does matter, sweetheart,” Blair told her. “You need to talk to someone.”

“I talk to you.”

Blair watched Amanda in the kitchen, moving from pan to bowl to silverware drawer to stove, her hands always moving, every gesture as graceful as a dance.

“You’re not lonely?” Blair asked quietly.

“No, Mom. I’m fine. I hate school. OK? But work’s fine and then I come home.”

“I know,” Blair said.

“Dinner,” Amanda announced, presenting the pan with a grand swoop of her arm. A perfect omelette.

“Bravo,” Blair said. She was a chef; her daughter had learned well. And she shared with her the appreciation of good food.

Amanda slid the omelette onto Blair’s plate.

“You eating?” Blair asked.

“Lasagna,” she said. “I told you.”

“How many nights will you work?” Blair asked. She tasted her omelette while they talked.

“It’s up to me. I can match the nights you work so we can be home on the same nights.”

“I might quit the restaurant,” Blair said, though she hadn’t thought about that yet. Her mind was racing through too many things—money, illness, leaving her daughter, and now this idea: leaving her work.

“Quit cooking? Why?”

“Burnout. I’m exhausted.”

“Since when? What are you talking about?”

Blair got up from the table. She turned, looking for somewhere to go.

“I’ve got to pee,” she said, heading into the bathroom.

She shut the door behind her and leaned back against it. Pressed hard against the spot where her mole had been, under her bra strap, the mole that scraped and bled and healed and scraped and bled. Until finally she showed her doc during a routine physical and the good doctor cut the mole, tested the mole and pronounced her dead on arrival. Melanoma. Advanced stage.

Why the hell didn’t you do anything about this?

Because I was busy. Because I’ve got a daughter and a crazy job and not enough money. Because I don’t pay attention to the details.

“Mom?”

“Coming.” She flushed the toilet and splashed water on her face. Opened the door. Sat down at the table. Knew that Amanda was watching her. She had told the doc, “I can accept dying. For me. But not for my daughter. She’s got no one else.”