Omelette and a Glass of Wine (5 page)

Read Omelette and a Glass of Wine Online

Authors: Elizabeth David

Tags: #Cookbooks; Food & Wine, #Cooking Education & Reference, #Essays, #Regional & International, #European, #History, #Military, #Gastronomy, #Meals

The Spectator

, 29 June 1962

August rain swishes down on the leaves of the wild jungly tree which grows, rootless apparently, in the twelve inch strip of gravel outside my London kitchen. I am assured by a gardener that the plant originated in Kamchatka, but now it looks more like something transplanted from the Orinoco. Staring out at it, hunched into her bumble-bee-in-a-black-mood attitude, my cat suddenly jumps up, presses her face to the window, doesn’t like what she sees, comes back, wheels round, washes her face, re-settles herself on her blanket, stares out again. I feel restless too. Remembering other rain-soaked Augusts, English holiday Augusts, I am melancholy, I have a

nostalgie de la pluie

. North Cornwall and its leafy lanes dripping, dripping; the walk in a dressing gown and gum boots through long squelching grass to the stream at the end of the field to fetch water for our breakfast coffee. At the nearest farmhouse they can let us have a pint or two of milk every day; no, not cream, and no eggs or butter, these come out on the grocery van from Penzance. Will there be any pilchards? How lovely to eat them grilled like fresh sardines, except we have only a primus in the kitchen, no grill or oven, so I don’t know how we’ll cook them; in the bent tin frying pan I suppose. The question never arises though, it isn’t the season they say, it’s too early, too late, too rough, too cold, too warm. Shopping in Penzance we run to earth what we think is a Cornish regional speciality. At Woolworths. Gingery biscuits, bent and soft, delicious, much nicer than the teeth-breaking sort. (Years later, I find tins of biscuits called Cornish Fairings at my London grocers, and buy them, hoping they are the same. They are meant to be, I think, but they are too crisp. I like the squadgy ones, I expect the recipe is secret to the Penzance Woolworths.)

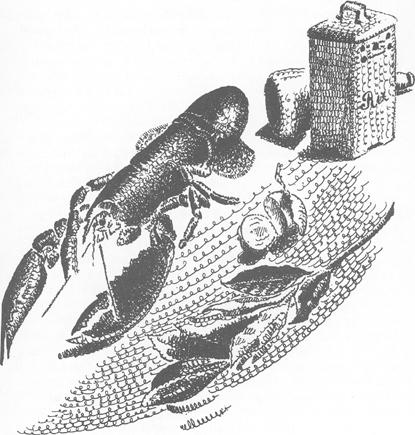

In one of the grey, slatey villages – St. Just in Roseland – we buy saffron buns, dazzling yellow, only the dye doesn’t seem to go quite all the way through, and I think it must be anatto not saffron, anyway there is no taste and the buns are terribly dry. Next day the children take up with a fisherman on the beach and he has given them a huge crawfish. How I wish he hadn’t. We can’t leave the thing clacking round on dry land. Dry – well, everything is relative.

D. says she will take the girls out for the afternoon to look for Lands End (yesterday it was curtained off by rain, she pretends to

think perhaps it will be different today) and leaves me to the grisly task of cooking the crawfish. The only advantage of being the Expedition’s cook is that I am entitled to stay indoors. Our largest cooking vessel is a 2-pint earthenware stew-pot, so I have to boil the lobster in the water bucket. The RSPCA pamphlet says the most humane way to cook lobsters and their like is to put them in cold water, and as it heats the animal loses consciousness and dies peacefully. I never met a fisherman or a fishmonger or a chef who paid any attention to this theory, and few who had even heard of it. I like to believe in it, and also I think that given the right conditions the system produces a better-cooked lobster, less tough than the ones plunged in boiling water, but a bucket of water takes a powerful long time to heat up on a small primus stove, and that animal would be lying in its bath for a good hour before the water boils – and suppose you have to take it off and re-charge the primus in the course of the operation?

*

The year after the Cornish coastguard’s cottage, it is a loaned bungalow on the West Coast of Scotland. Rain drumming on the corrugated iron roof makes a stimulating background rhythm for my work on the index of a book about Italian cooking. Thank heaven for these wet Augusts. In what other climate could one do three months’ work during a fortnight’s holiday?

Gragnano, grancevole, grignolino, gorgonzola, granita, San Gimignano

, no,

Genoa, ginepro

. L. comes in drenched but with a fresh supply of Dainty Dinah toffees and the delicious rindless Ayrshire bacon we have discovered in the village shop, and the information that at high tide the fisherman will be at the landing stage with crabs and lobsters for sale. Must we? Lacrima Cristi, lamb, lampreys, Lambrusco, lasagne … All right, on with our Wellingtons and sou’westers. As it turns out the fisherman is

not

selling crabs and lobsters, nobody eats them here, nasty dirty things, they are for despatch to a fish paste factory in Yorkshire. I am relieved. Too soon. He holds out a great rogue crab. Here, take this. Sixpence. ‘How shall I cook him? In boiling water or cold?’

‘Boiling.’

‘The RSPCA says–’

‘Don’t know about that –’

‘–cruel–’

‘Dirty beast. Let him suffer it out.’

*

On Tory island, off the Donegal coast – two hours off, in an open boat, on what the Irish describe as a nice soft day, the Scots as a bit mixed, and I as a hurricane, a woman tells me that the best way to cook crabs is to pull off their claws and roast them in the ashes and throw the truncated bodies back in the sea. Some evidence of this ancient folk custom was indeed around. After all perhaps I am better off not inquiring too closely into the local cookery lore of these islands. The kind of windfall cookery which comes one’s way in London demands a less ferocious spirit. Rapid action is more to the point.

Pale apricot coloured chanterelle mushrooms from sodden Surrey woods have only to be washed and washed and washed until all the grit has gone, every scrap, and cooked instantly before the bloom and that extraordinary, delicate, almost flower-like scent have faded. (As L. was returning to our Scottish bungalow that other year with a damp bundle of these exquisite mushrooms gallantly gathered during a storm, the schoolmaster’s wife stopped to look and used the same expression as the fisherman did about the crab – ‘You’re never going to eat those dirty things?’ But she was a kindly woman, and the same evening invited us in for whisky which would dispel the effects of our folly.)

In contrast, a bunch of sweet basil, the kind with big fleshy floppy leaves, fills the kitchen with a quite violently rich spice smell as it is pounded up with Parmesan, garlic, olive oil and walnuts for a

pesto

sauce for pasta. Again, action has to be taken immediately. That basil was wet, and by tomorrow will have begun to turn black. The vine leaves from the wall of a house near Cambridge, now they can wait a day or two, wrapped in a food bag in the refrigerator, then they will make a lining for a pot of baked mushrooms – a recipe of Italian origin intended for big fat boletus and other wild fungi, and which, it turns out, works a notable change in cultivated mushrooms, making you almost believe you have picked them yourself in some early morning field.

The brined vine leaves in tins from Greece work perfectly in the same way too – all that is necessary before using them is a rinse in a colander under running cold water – but fresh ones, a couple of dozen or so if they are small, should be plunged into a big saucepan of boiling water. As soon as it comes back to the boil take them out, drain them, and line a shallow earthenware pot with them, keeping some for the top. Fill up with flat mushrooms, about ½ lb for two, scatter the chopped stalks on top, add salt, freshly milled pepper,

several whole small cloves of garlic which don’t necessarily have to be eaten but are essential to the flavour, pour in about four tablespoons of olive oil and cover with vine leaves and the lid of the pot and bake in a very moderate oven for about one hour – less or more according to the size of the mushrooms. When the vine leaves are large and tough they do their work all right but are too stringy to eat; little tender ones are delicious (not the top layer, they have dried out) and there is a good deal of richly flavoured thin dark juice; for soaking it up one needs plenty of bread.

The Spectator

, 24 August 1962

From where I am sitting it looks very much as if this were another apple-glut autumn, like that of 1960. No question here of ‘at the top of the house the apples are laid in rows’; they are in bowls and baskets, under the stairs and in the passage and on the kitchen dresser; spotty windfalls, a couple of dozen outsize Bramleys, mixed lots of unidentified garden apples, sweet and sour, red, yellow, brown, green, large and small, from old country gardens where, at any rate in the south, the trees appear to be exceptionally heavily laden this year. Commercial crops of both eating and cooking apples are, I am told, no more than average and, like all our crops this year, have ripened at least a month late; not that that excuses those growers who send their Cox’s orange pippins as unripe to market as some I’ve tasted recently and which make one wonder if the reputation of yet another of our cherished home-grown products is on the way to extinction owing to the short-sightedness of the growers.

Those Bramleys now. What to do with them? There are some who say they make wonderful baked apples. Not I. I find them too large, too sour and too collapsible; and in any case I believe there is no more chilling dish in the whole repertory of English cooking than those baked apples with their mackintosh skins and the inevitable fibrous little bits of core left in the centre; and again, because of the way they disintegrate Bramleys are of very little use for the kind of apple dishes which go so wonderfully with pheasant and other game birds and duck. At the Cordon Bleu school in Paris the other day I

saw the chef demonstrating quails

à la normande

; roast quails served on a bed of sliced apples, cooked in butter in a sauté pan; they were seasoned with salt

and

sugar, enriched with thick bubbling cream and a good measure of calvados. Delicious; but well-flavoured and aromatically scented dessert apples which keep their shape are essential. I have used those aforementioned unripe Cox’s, which make good fried apples; better still, of course, if the apples are ripe. Both Eliza Acton – where fruit cooking of any and every kind is concerned she is unbeatable – and her twentieth-century French counterpart, Madame Saint-Ange,

1

are very insistent about the quality

and

ripeness of apples for cooking, but Miss Acton doesn’t mention Bramleys, probably because although they were already known in her time (discovered, it is said, in a garden at Southwell in Nottinghamshire in 1805) they were not commercially cultivated until the 1860s, some fifteen to twenty years after she wrote

Modern Cookery

.

For apple jelly, for example, Miss Acton specifies Nonsuch, Ribstone pippins and Pearmains, or a mixture of two or three such varieties; and for that most elementary of nursery dishes – which can be such a comfort if nicely made and so odious if watery or over-stewed – which we call a purée and the French call a

marmelade

, Madame Saint-Ange demands, as do nearly all French cooks, the sweet apples they call

reinettes

, the pippins of which the old-fashioned russet-brown

reinette grise

is the prototype.

All these are counsels of perfection; Bramleys are our problem now (the apple publicity people tell me that there are three million Bramley trees in England today), so with Bramleys I make my apple purée, and the recipe I use is the one Miss Acton gives for apple sauce. There is nothing much to it except the preparation. Every scrap of peel and core must be most meticulously removed because the purée is not going to be sieved. You simply heap the prepared and sliced apples into an oven pot, jar or casserole and bake them, covered, but entirely without water, sugar or anything else whatsoever, in a very moderate oven (gas no. 3,330°F) for anything from twenty to thirty minutes. To whisk them into a purée is then the work of less than a minute. You add sugar (according to your taste and whether the purée is to serve as a sauce or a sweet dish) and, following Miss Acton’s instructions, a little lump of butter. I think perhaps this final addition provides the clue to the excellence of this

recipe, and if it sounds dull to suggest the plainest of apple purées (cream and extra sugar – Barbados brown for preference – go on the table with it) as a sweet dish I can only say that there are times when one positively craves for something totally unsensational; the meals in which every dish is an attempted or even a successful

tour de force

are always a bit of a trial.

And how grateful hospital patients would be if such a thing as a good apple purée were ever to be produced in these establishments; it is just the kind of food one needs when not too ill to be interested in eating, but not well enough to face typical hospital or nursing-home cooking.

One point I should add for the benefit of anyone who has no experience of the idiosyncrasies of the Bramley apple: after fifteen minutes the slices may appear nowhere near cooked; five minutes later you find that they have burst into a froth which has spilled all over the oven; so it is advisable to fill your dish no more than half-full to start with.

The Spectator

, 26 October 1962

*

The title of this article was less than fortunate. The English Apple and Pear Board which in the person of Robert Carrier, its PR representative, had helped me with information, was not amused. A lady from Todmorden in Lancashire wrote to my editor in ferocious terms about his cookery expert, furiously condemning ‘the revolting brown jam-like apology for the real thing’ which my Eliza Acton recipe would certainly produce. When some cherished culinary tenet comes under attack from a journalist people do write letters like that. As a matter of fact I had been a bit surprised myself when I opened my Friday

Spectator

that week. I had not been conscious of launching a deliberate attack on the Bramley. It can only have been my unflattering remarks about English baked apples – a criticism directed at the method of cooking rather than at the object cooked

–

which prompted the literary editor or his deputy to give my otherwise fairly mild piece so provocative a title. In weekly journalism naming of articles tends to be rather a last minute affair, so when my proof came in there had naturally not been any hint of bad about my big Bramleys. Anyway, the deed was done, and having apologised as best I could to Robert Carrier, I began to think the

little commotion had been rather entertaining. In my household, I regret to say, Bramleys had already become forever big and bad

.