Okay for Now (11 page)

Authors: Gary D. Schmidt

"You're supposed to shake my hand," said Lil.

That is what I did.

After she left, I worked on my drawing of the Large-Billed Puffins. And even though their round

eyes are looking away and out of the picture, I decided to change one small thing, so when Mr.

Powell came up to see how I was doing, he looked at them, then at me, and then back at them. "It

seems that they like each other," he said.

"Maybe," I said.

A week later, while we were taking another try at the puffins—you can't believe how hard it is to

make a puffin not look like a chump—I told Mr. Powell about Miss Cowper and Charlotte Brontë and

Jane Eyre.

Mr. Powell wanted me to work on the bills and the feet, since they were at crux points in

the composition, he said. (Artists know what this means.) But it was hard to make these look right,

mostly because they look so stupid.

"

Jane Eyre,

" he said. "

Jane Eyre,

" he said again.

"The original novel is four hundred pages long," I said.

He nodded.

"We have to read an abridgment, and it's still a hundred and sixty pages long."

Nodding again.

"I'm not reading it," I said.

"Mr. Swieteck, if it's an assignment—"

"I'm not reading it."

I went back to getting the feet right, and the stupid bills.

"I can help," Mr. Powell said after a bit.

"I can't get this one foot that's underwater right."

"With

Jane Eyre,

" he said.

I looked up at him. "I don't need any help with

Jane Eyre

because I'm not going to read it."

We didn't talk about

Jane Eyre

anymore. I went back to the puffins.

And I know you think you know why I don't want to read

Jane Eyre,

but it's not really any of your

business, is it?

When I got home from the library, my mother was cooking everything in sight. Here are the stats for

what was on the kitchen table and counter:

Three loaves of fresh-baked white bread.

One angel food cake with chocolate icing dripping down its sides—Lucas's favorite.

Probably two hundred carrots she'd sliced.

Probably three hundred green beans she'd cut.

Probably four hundred yellow beans she'd cut.

Three dozen ears of corn shucked.

Thirty-five huge patties of hamburger already cooked and wrapped in tinfoil.

One bowl of Italian macaroni salad.

Two bowls of German potato salad.

One bowl of green grapes.

Two platters of tomatoes, sliced.

One platter of onions, sliced.

"Mom," I said.

Everything was piled almost on top of everything else. Bacon was frying on the stove. She was

cutting up canned peaches and pears to go in three chilled Jell-O salads.

"Oh, Douggie, Douggie," she said. "I'm so glad you're home. Look at this."

She held up an envelope.

There was a U.S. Army insignia in the left-hand corner.

"It's got to be from Lucas," I said.

"But the address isn't his handwriting," she said.

She was right. She went back to cutting the peaches and pears into smaller and smaller pieces. The

liquid Jell-O was cooling on the stove.

"You better open it," I said.

"You open it," she said.

I opened the letter and took it out. It was in script, so it was really hard to read. I held it out to her.

She looked at me, turned to wash her hands, looked out the window, turned back and looked at the

letter, and finally took it.

Her terrified eye.

Then she read aloud the most important parts.

That a friend of Lucas was writing the letter for him. That Lucas had been wounded pretty bad, but

was mostly okay now. That he would be home in a couple of months, maybe three, maybe a little

more, depending on how things went. You know the army. That he hoped we wouldn't mind if he

looked a little bit different. Everyone comes home from Vietnam a little bit different.

That Lucas couldn't wait to see us.

She held the letter against her chest. She looked at me. She closed her eyes.

"What is it?"

"He says he can't wait to see us," she said in this squeak of a voice.

She put her hands to her face.

"Mom?"

"And he says that he loves us."

She opened her eyes and looked at the letter again, folded it, put it back in its envelope.

She put it up on the window ledge, over the kitchen sink.

You know, you know, how can you smile like that, and be sobbing and sobbing all over the peaches

and pears?

CHAPTER FOUR

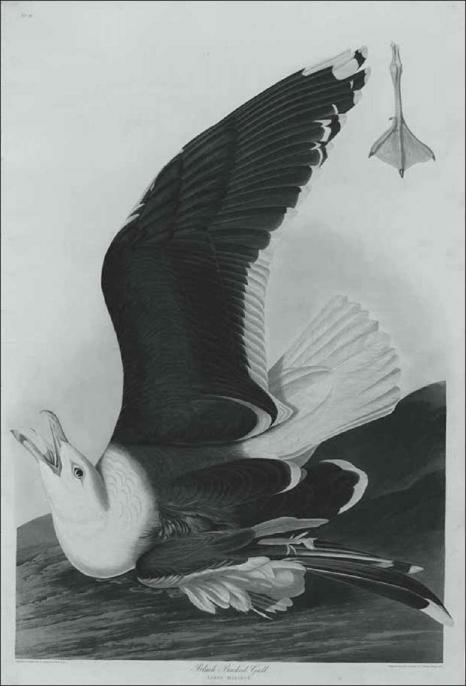

The Black-Backed Gull

Plate CCXLI

"THAT LEFT FOOT has to feel like it's in the water.

In

it, Mr. Swieteck. Not in front of it. You want to

give the impression of depth."

"I know the stupid foot is in the stupid water," I said.

"So how does Audubon help you to know it?"

"He changes the color of the foot."

"How else?"

"The lines aren't as sharp."

"Exactly. The whole form of the foot starts to blur. The texture fades away. You can't even see the

webbing between these two toes."

"So how do I..."

"Take your pencil and we'll lighten the strokes here, and bend them just a bit, since light is bent

when it enters the water. Now, follow my hand."

You think this is easy? I'm not lying, it isn't. I'd been working on the Large-Billed Puffins all

September, and most of the time I was working on the stupid fading foot, because an artist doesn't

draw two-dimensionally, in case you didn't know. An artist draws three-dimensionally on a two-

dimensional surface, which Mr. Powell pointed out to me and which I pointed out to Lil Spicer.

"How do you do that?" she asked.

"You have to be an artist to know," I said.

And if you think she said,

Then how do

you

know?

or something snotty like that, she didn't. Figure

out why.

Things at Washington Irving Junior High School were going mostly okay. Mostly. Nothing had

happened to

Geography: The Story of the World,

which was good because Mr. Barber checked on

my book every time he passed down the aisle drinking his huge cup of coffee. I think he didn't care

that I wasn't turning in my answers to the Review Questions at the end of the chapters because that

meant I wasn't messing up his new geography book. Mr. McElroy had been showing us filmstrips

about the barbarian hordes of Russia with records that gave little pings to let him know when he was

supposed to advance the strip. You can't believe how many filmstrips there are about the barbarian

hordes of Russia. Miss Cowper still hadn't made us start stupid

Jane Eyre,

so we had all 160 pages

to look forward to—not that it mattered, because I wasn't going to read it. Mrs. Verne hadn't called on

me yet when I raised my hand, but she

had

called on me when I didn't raise my hand so that she could

trip me up and show everyone what a chump I was. But I figured that's what she was up to, and so

when she asked if I knew what a quadratic equation was when she thought that no one in the room

knew except for her, I knew. I hadn't pulled any funny business in Coach Reed's PE class—no sirree,

buster—except that I sneaked over to the Shirts Team from the Skins Team when we finally played

basketball after two weeks of dribbling and shooting drills. And in Mr. Ferris's class, Lil and I had

done our first lab report together on creating a supersaturated solution, which meant that I did all the

smelly chemically stuff and Lil took down the notes and wrote it up.

Oh, and I don't mean to brag or anything, but that lab report that Lil and I turned in for the

supersaturated solution? Let's just say that Mr. Ferris started Clarence rocking when he saw it.

But I still couldn't get that left foot of the Large- Billed Puffin right. It always looked like it was in

front of the water.

I worked on it all weekend when my brother wasn't around (which was most of the time) and when

my father wasn't around (which was all of the time). I even showed it to my mother, but you can't trust

mothers to tell you the truth about stuff like this. They just tell you how good it is and what an artist

you are and how they don't know where you got that talent since no one else in the family can draw.

But I still couldn't get the foot right.

On Sunday night, after my mother and I ate four thawed hamburgers and one large bowl of Italian

macaroni salad, I decided to try for some inspiration, which is something that every artist needs. So I

went downstairs to the basement and got Joe Pepitone's jacket and put it on. Then I went back upstairs

to my room and rolled out the paper and tried to fade that foot into the water, because an artist has to

know how to give an impression of depth, you might remember.

And I started to get it. I really did.

And then my brother came home—and upstairs—and into our room. And first he said, "How come

you're wearing a jacket when..." and then he saw the drawing of the Large-Billed Puffins and then he

laughed because he wouldn't know a decent drawing if it walked up to him and punched him in the

face, so he grabbed it like the jerk he is and looked at it and laughed again and said, "Can't you even

draw a foot right? It looks like it's underwater, Douggo," and then he tore it up and said, "I guess

you'll just have to try again," and then he scattered all the pieces on my bed because that's what

twisted criminal minds do.

Then, still laughing, he left, not even noticing that I had Joe Pepitone's jacket on, the chump—

which, of course, I was glad about, since it was a pretty close call. I went back down to the basement

and hung it up beneath the stairs again.

And you know what?

I was smiling. I was smiling like all get-out.

If you were paying attention back there, you'd know why.

So on the first Saturday of October, after a week when Mr. McElroy had had enough of the Russian

hordes and had probably run out of pinging filmstrips anyway and so we were now headed across the

Great Wall into China, and a week when Mrs. Verne finally did call on me when I had my hand up and

when I answered right—not to brag—that it was negative

x

and not negative

y,

and a week when I had

snuck over to the Shirts team again and Coach Reed couldn't figure out why his platoon system wasn't

working and how someone was pulling some funny business on him, I went over to the Marysville

Free Public Library after my deliveries, ready to tell Mr. Powell that I had figured out how to give the

impression of depth. Mrs. Merriam with her loopy glasses looked up when I came in.

"He's in a meeting," she said.

"Is he done soon?" I said.

"He's in a meeting. That's all I know. It's not like I've memorized his schedule. I'm just supposed to

do all this cataloging by myself, I suppose."

I went up to see the Large-Billed Puffins. Maybe I ought to give them names, since it felt like we'd

gotten to know each other.

But they were gone. Just like the Arctic Tern.

This time, the page was turned to a dying bird. And I mean, really dying. Most of the picture was

this one wing, held straight up. All its feathers were spread out, and you could see how Audubon got

their pattern down—three rows of long, overlapping dark feathers, tipped white at the ends. You

could feel how the wind would cruise over them. It was so beautiful, and it's what you looked at first.

And then you looked down at the second wing, which was crushed.

And then you looked at the belly of the bird, which was spouting thick red blood all over the dark

feathers.

And then you looked beneath the bird, where the blood was in a puddle.

And then you looked at the bird's head. After that, that's all you looked at.

I would have given Joe Pepitone's jacket to save this bird.

His beak was wide open and his tongue was stretched out into a point. He was screeching while

his blood ran. His head was pulled far back, like he was taking one last look at the sky that he would

never fly in again. And his round eye told you he knew that everything was ruined forever.