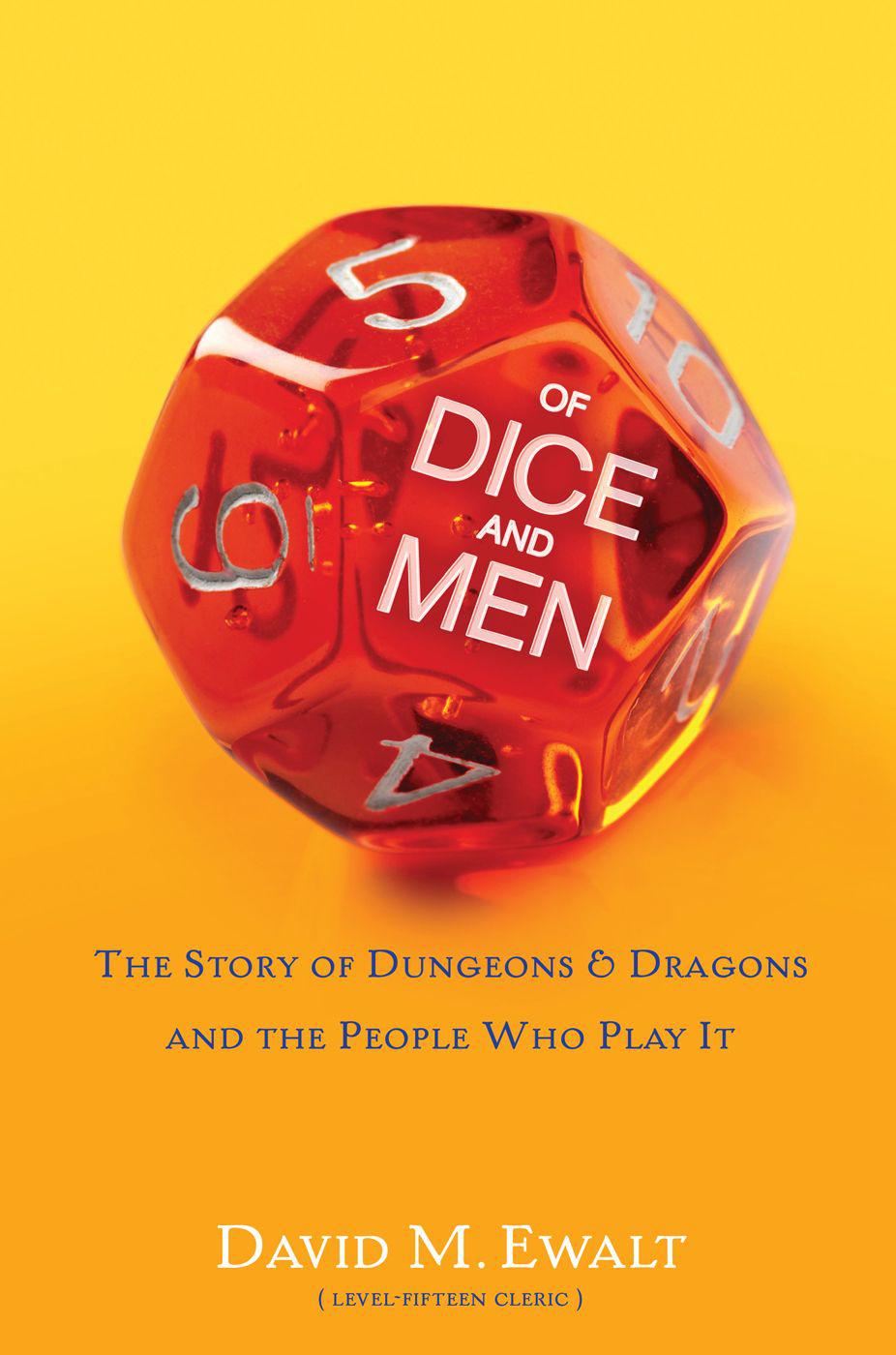

Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and The People Who

Read Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and The People Who Online

Authors: David M. Ewalt

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

7

The Breaking of the Fellowship

For Kara

B

efore we begin, I’d like to take a moment to address the hard-core fantasy role-playing gamers in the audience. If you’ve ever painted a lead mini, tried to wear the Head of Vecna, or know what happens if you flip a flumph on its back, please continue. Otherwise, feel free to skip straight to the first chapter.

Okay. Now that we’ve gotten rid of the muggles, there are a few points I want to cover.

First of all, at various points in this tome I quote specific elements of the Dungeons & Dragons rules, including game mechanics, spell effects, and monster descriptions. Unless otherwise noted, these citations refer to version 3.5 of the D&D rules. I default to those books because they’re what I use with my friends, and I like them. Gamers who wish to argue the superiority of their own favored edition are advised to write a letter detailing their position, put it in an envelope, and then stick it where the Sunburst spell

1

don’t shine.

Second, when describing in-game action, you may note that I

sometimes break initiative order or skip over a player’s turn. This is a conscious decision made to emphasize the drama in an encounter and not get lost in excruciating detail. Rest assured that everything described in-game actually happened in-game, and if I leave out the time Bob the Halfling fired his crossbow and missed, it’s because nobody cares.

Finally, while I am confident that even the most grizzled of grognards can learn something from this volume, keep in mind it is largely intended to explain the phenomenon of D&D to a mainstream audience. If you seek a detailed history or obscure arcana, you have just failed your Gather Information check. Fortunately, there is a wealth of scholarship available on the subject, and you’ll find a list of some of the best sources in the back of this book.

In short: Read this like you’d play in a friendly campaign. Don’t be a rules lawyer, and don’t argue with the DM.

1

. “Sunburst causes a globe of searing radiance to explode silently from a point you select. All creatures in the globe are blinded and take 6d6 points of damage.”

Player’s Handbook,

p. 289. See how I did that?

YOU’RE ALL AT A TAVERN

T

he day I met Abel, Jhaden, and Ganubi, we got arrested for brawling in a bar.

In our defense, we were fighting for a righteous cause. One of the regulars was six beers past tipsy when he started running his mouth and spouting the worst kind of reactionary politics. Abel and I found it offensive and told him to shut up; Jhaden isn’t much for talk, so he hit the guy with a stool. Rhetorical became physical, and the four of us lined up on the same side of the dispute.

The cops must have been nearby, because the next thing I knew they were throwing us in the back of a wagon. We stewed in a cell overnight before Jhaden was able to use some kind of family connection to get us released. I don’t know what happened to the drunk guy.

A thing like that will bond a group of young men pretty quickly, and soon we were spending most of our time together—sharing a couple of rooms in a cheap boardinghouse, working together on whatever

freelance gigs we could find. The jobs weren’t always on the books, but we felt like we were doing good work.

Jhaden was strong as a bull, Ganubi a natural charmer, Abel educated and clever. We got in our share of fights, but I had worked in a hospital, and when anyone got hurt, I’d do my best to patch them up.

I’d like to think I did my part in combat, too—shooting searing rays of light out of my fingers, stunning enemies with thunderclaps of sonic energy. Sometimes I’d summon a giant badger from the celestial planes and command it to do my bidding. Few things end a fight quicker than a magical weasel chewing on your opponent’s leg.

I am not a wizard, but I play one every Tuesday night. To be nerdy about it—and trust me, there is no other way to approach this—I am a divine spell caster, a lawful neutral twelfth-level cleric. In the world of Dungeons & Dragons, that makes me a pretty major badass.

Dungeons & Dragons—D&D, to the initiated—is a game played at a table, usually by around half a dozen participants. It’s sold in stores and has specific rules, like Monopoly or Scrabble, but is otherwise radically different. D&D is a role-playing game, one where participants control characters in a world that exists largely in their collective imagination.

Even if you’ve never played D&D, you’ve probably heard of it, and when I admitted I’m a player, your subconscious mind probably filed me under “Nerds, Hopeless”—unless you happen to be one of us. Role-playing games don’t have a great reputation. In movies and TV shows, D&D serves as a signal of outsider status. It’s how you know a character’s a hopeless geek: A rule book and a bunch of weird-shaped dice is to nerds what a black hat is to the villain in a cowboy movie.

Most people know D&D only as some strange thing the math club did in the corner of the high school cafeteria, or the hobby of the creepy goth kid down the street. Even worse, they have the vague sense it’s

deviant or satanic—don’t D&D players run around in the woods and worship demons, or commit suicide when they lose a game?

Admitting you play Dungeons & Dragons is only slightly less stigmatizing than confessing cruelty to animals or that you wet the bed. It is not to be done in polite company.

But I am immune to your scorn. I know magic.

Jhaden, Abel, Ganubi, and I are freedom fighters. The shared politics that brought us together in that bar are more profound than liberal or conservative; we’re all proponents of an active approach to humanity’s problems. We want to organize the workers of the world and to strike out against those who would hold us in bondage.

In contrast, our opponents fear change. They don’t want to upset their comfortable bourgeois lives or take risks that might overturn the political order. Time is on our side, they say—real progress occurs slowly, over generations. They think we should wait and things will work themselves out.

It’s so cowardly and stupid. You can’t wait out vampires.

Let’s start with a brief overview, for the uninitiated: Dungeons & Dragons takes place within a fantasy world that is invented by its players but inspired by centuries of storytelling and literature. Books like J. R. R. Tolkien’s

Lord of the Rings

helped set the tone: heroic knights and wise old magicians battling the forces of evil. A typical D&D session might find a party of adventurers setting off to search an underground cave system for treasure and having to fight all the slobbering monsters lurking in the dark.

But D&D isn’t a board game with a preprinted map and randomized game play (roll a die, move four spaces closer to the treasure, pick up a card: “You got scared by a goblin! Go back two spaces”). Instead, each setting is conceived in advance by one of the participants and then actively navigated by the players.

The person who does all the prep work is called the Dungeon Master, or DM. It’s his job to dream up a scenario, something like “Archaeologists have discovered a pharaoh’s tomb in the desert, and the players are grave robbers who have to break in and steal the hidden treasure.” He also has to sketch out the details, like making a map and deciding where the traps are, where the treasure is, and what monsters are guarding it.

This act of creation gives the players an unknown world to explore and keeps each game session different from the last. It’s sort of like sitting down to play Monopoly, except you can’t see the names or costs of the properties until you land on them.

An experienced DM takes game design even further. He might decide the players should start out in a Bedouin camp near the tomb and negotiate with the sheik to buy a couple of camels. He could plan for them to be waylaid by desert raiders on the way to the tomb. And once they’ve found the pharaoh’s treasure, he may ask them to make a moral choice: The treasure carries a curse, and if it’s removed from the tomb, the region will suffer ten years of famine. The players will have to weigh getting rich and letting thousands die against leaving empty-handed and protecting the innocent.

At this level, setting up a role-playing game becomes something like writing a screenplay or novel. And just as fantasy fiction may include all kinds of different settings and plots, a fantasy role-playing game does not have to be constrained to a standard medieval setting.

Vampires have always hunted man, but we were not always in their thrall. For millennia they hid in the shadows, keeping their numbers small, feeding only on humans who wouldn’t be missed. The few stories that betrayed their existence were dismissed as urban legend or lazy fiction.

But at the beginning of the twenty-first century, something changed. Vampires were tired of hiding, of letting weaker humans ruin the planet. So they gathered, and they plotted, and one dark night, they struck.

Most humans died without ever knowing their enemy. The vampires had magically bound our leaders to their will, and on their command, the armies of the world exploded upon one another. Those who survived the first strike had nowhere to hide: A magically enchanted retrovirus mutated ordinary animals and plants, turning them into monsters that overran both ruined cities and poisoned wilderness.

What few shreds of humankind remained were easily rounded up, brought to a dozen vampire-controlled cities, and locked into pens, like cattle. Our species survived, but only as a food source for Earth’s new masters.