Observatory Mansions (7 page)

Read Observatory Mansions Online

Authors: Edward Carey

If pyloric stenosis occurred, if the Porter ceased to clean, we would drown in dirt and rubbish.

On my single visit to the Porter’s flat I gave myself a

souvenir. The Porter’s duplicate uniform was hanging tidily, spotlessly in the Porter’s wardrobe. I took for myself a single brass button (lot 803). A while after taking this button the Porter confused me. I always saw him immaculately dressed in his uniform

without a button missing

. At first I presumed that he only wore one uniform. Then I presumed that he purchased a replacement button. Finally, I understood. Three buttons down, the thread was always a slightly different colour. I imagined the Porter settling himself down when the time came to change uniforms, with a needle and thread, transferring a single brass button from uniform jacket to uniform jacket.

On that first day the new resident spent with us, the Porter, having finished removing proof of my entrance, went in search of other dirt. I descended to the cellar.

The journey to meaning

.

Down below where the carpet stopped, where nothing was on display for the residents and was out-of-bounds for all but the Porter, the dust lay heavily. It had blunted every corner and, resting on foundations built by spiders’ webs, it had created phantom ceilings and phantom walls. The cellar was the length and width of the floors above it, it had a vaulted brick ceiling, the same ribbed pattern all over it, with plain columns at every segment, like roots to an enormous tree. These multitudes of columns that supported the house were ideal to hide behind. Ideal, I remembered from my childhood, for tying fishing line around at ankle height and watching servants trip over. And there was also a tunnel which began in the cellar and ran all the way to the nearest church, some half mile away. This tunnel was all that remained of the sixteenth-century manor house that had burnt down.

This is where I went. This is what I was searching for. Past

the Porter’s flat, past the boiler rooms, past the sheets of plasterboards and rolls of blue and white striped wallpaper (remnants of the conversion of Tearsham Park to Observatory Mansions) was a door. I can see it now and as I see it I become vaguely tearful. A door marked DANGER – ENTRANCE FORBIDDEN. My door. Sealed with a heavy padlock to which I alone kept the key.

Stretching out across the long passageway that led to the church, kept in existence by numerous wooden beams which supported the roof and walls, with just enough space remaining to provide a narrow walkway, were the nine hundred and eighty-five objects of my exhibition.

It was possible to understand my history from this exhibition. Like layers in a rock face, the years and stages of my life were encoded there. The exhibition also revealed the life of the city, changes in taste, in fortune, in its people.

Each exhibit was placed inside a polythene bag and sealed with tape to keep away damage from condensation. At the foot of each exhibit was a small sign written on cardboard in standard biro black: the exhibit’s number.

I, the exhibition’s owner, archivist, attendant and public, wandered down the fringe enumerating: One, two, three … There they all were, all swaddled in polythene, all the dears, many years’ work. All my own.

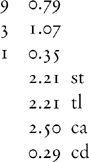

I began the collection, my pride and joy, way back when at fourteen years of age I found a till receipt that had been exhaled by the wind on to the driveway of Observatory Mansions, a time ago when the house was called Tearsham Park. I was outside, ordered under the sky by my mother for the purpose of taking some physical exercise. My white, lace-up footwear, designed for sportsmen (a fraternity that I have never belonged to), was enjoying the pursuit of kicking a pebble up and down, forwards and back. I missed the object, scarred the earth and brought the till receipt accidentally to the surface. Lot number one, by the entrance:

Fine Quality Foods

Thank you for your custom

This seemingly dull piece of flotsam ensnared my inquisitiveness. I rescued the tear of paper. Who was at the shop? What did the person buy? Where did the person live? Male or female? Married or single? Ugly or pretty? Young or dying? Will I ever know you? All the questions were unanswerable, so I conceived people from my mind to fit the receipt. The receipt was wrapped in cling film and hidden under my bed and bothered daily for many a week and month until it was creased all over and became extremely fragile.

Other articles supplanted the love I felt for the first. New histories were created. At first I collected unimpressive objects: empty boxes, plastic bags, empty bottles and cans, used envelopes, pencil stubs – in short, objects that had been rejected, that had either been spent or disregarded, objects that other people might have termed collectively

rubbish

. Then one day I set out a new rule. I bought a hard-bound notebook, hereafter called the exhibition catalogue, and wrote on its first page: IT IS REQUIRED OF ALL EXHIBITS, FROM NOW ON, THAT THEY ARE TO BE EXHIBITED SOLELY FOR THE REASON THAT THEY ARE LOVED; THAT THEIR FORMER OWNER PRIZED THEM ABOVE HIS OR HER OTHER POSSESSIONS, THAT THEY ARE ORIGINALS, THAT THEY ARE IRREPLACEABLE.

In time the collection grew too abundant to keepin my bedroom and was relocated piece by piece to the cellar, a three-month programme of exodus. At first they were hidden

in the wine cellar, which like many parts of the estate was out of bounds for children; this parental warning ensured that these forbidden corners quickly became my favourite hiding places.

Time walked on.

Then Francis Orme, not one day out of many, but not unsuddenly, was child no more. Then Francis Orme, white gloved, was declared past child age.

Time walked on.

Then it was announced that the park was changing its name to Observatory Mansions and building work began. The wine cellar was to be transformed into a basement flat. A three-roomed cage hidden amongst the dust and dirt.

The fat and thin Cavalier

.

I had been told ghost stories of the corpulent courtly gentleman (also an Orme, also called Francis – every first-born male Orme was named Francis – though this Francis Orme was called Sir Francis Orme) who was too large to escape down the cellar passageway to the sanctuary of the church, which, by fault of design, narrowed as it progressed. I had been told how the Cavalier became stuck down there in the dark, wedged himself in so perfectly that he could neither advance nor retreat. And in the miserable darkness, his ribs crushed, unable to turn around, bleeding at head and broken at fingers, he died. His skeleton was discovered decades later collapsed on the floor, with his once tidy uniform rotting around him. Only after death had the Cavalier thinned enough to be set free. This legend had been told to my child self with the correct degree of drama and suspense that I swallowed it utterly and vowed never to wander along the church passageway where I would surely be trapped against a circle of wall

and be unable to wriggle free. Nobody, I was told, would ever come looking for me if I got chocked up there, for that is where the Cavalier lives, and no one wants to meet the fat and thin Cavalier.

So, armed with burning candle and box of matches, lest I should shiver the flame out, I moved the exhibition once more to that safest of places where my parents wouldn’t come searching if I screamed out at eighty decibels. No one must discover you.

Never. Never, ever

. It was such a perfect hiding place, even the Porter did not come to this part of the cellar. Too much dirt. Of course, I had to protect my gloves down there. Small concession. Whenever I went to the cellar I wore my father’s brown leather gloves over my white cotton ones. And for nineteen years I kept the exhibition a secret there. Until the new resident came.

The Object

.

One object was always moving. This was my most precious possession. It was the inspiration for which the exhibition kept multiplying. It was the most delicate, intricate and clever object that I had ever known, the object above all other objects, which was always moved to the end of the exhibition. It must always seem to be the exhibition’s newest item, never supplanted in love by any other exhibit. It was the exhibition’s greatest glory and was called simply, with love and awe,

The Object

.

And next to that sacred object I placed so tenderly object number nine hundred and eighty-six. A scratched toy Concorde. I did not need to conceive a history for this object. I had viewed enough by seeing the child’s tears as the plane and child parted company.

As I concentrated I licked my bottom lip, as had been my habit for a long time when gripped with exhibition passion. And so, after a while, my lower lip became swollen.

I spent an hour amongst my friends, walking up and down the narrow corridor, seeing that they were all safe, talking to them, sharing with them. Eventually, I returned, with regret, to the world above.

On reaching the top of the stairs that led to the entrance hall, I heard a voice. The voice that belonged to the bespectacled blur I have already mentioned. The blur was now in focus. The voice said:

What’s down there?

It said:

What’s down there?

II

MEETINGS

Our first conversation

.

What’s down there?

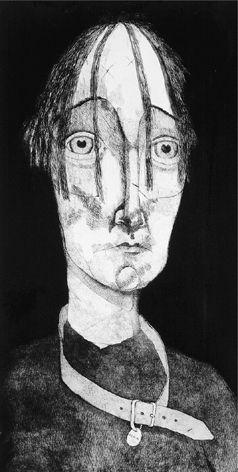

I was looking into the pale face of the new resident. It was a round face with a tight chin, delicate, well-formed ears and a small nose which pointed slightly upwards. She had two freckles, neither big – both about the size of a pin head – one on the left cheek, the other on the tip of the nose. She had clean black hair, which had permission to grow to just above the nape of the neck, and thick black eyebrows. There was nothing else of immediate significance, save the two objects worn by her face. The first was a cigarette; the second, a pair of round, steel-rimmed spectacles, their powerful lenses magnifying the eyes behind them. The eyes, and this was difficult not to notice, were green and seemed extremely sore, somehow infected. Combining all the features together (though they may perhaps have been separately attractive) resulted in a slightly sickly, unenviable portrait. The new resident was not pretty.

What’s down there?

The new resident stood a little over five feet tall, she wore a plain, dark blue dress and flat-soled, black, lace-up shoes. Her hands were thin and bony. The right hand had a mole between the knuckles of its forefinger and thumb. Both hands were ugly, both were callused.

What’s down there?

Nothing.

Is it the cellar?

What are you doing here?

Sorry. My name is—

Don’t tell me your name. I’ve no need of it.

Then what’s your name?

You’ve no need of it. I shan’t tell you.

Do you live here?

I do. Get out.

Good. Let me explain, I’m new. I live in flat eighteen.

Why?

It’s my home, I’ve bought it.

Why?

I liked it.

What about it?

I wanted to live in this part of the city.

Why?

That’s my business.

When are you leaving?

I’m not leaving.

I want you out by the end of the week

.

But the new resident, rather than beginning an argument or bursting into tears, simply smiled, as if she had suddenly seen or understood something, and said:

Of course, you’re the one who wears gloves.

Don’t touch me.

You’re Francis, aren’t you?

The Porter told you my name!

You’ll get used to me, Francis. See you later.

And I stood, mouth wide open like an imbecile, and watched her walk out of Observatory Mansions. I don’t think she had listened to me at all, I don’t think she had any intention of leaving. I closed my mouth and stepped out after her.

The new resident was the other side of the roundabout being weighed by the man with the bathroom scales. She was talking to him, he talked back. I did not hear the words, I was too far away, held back by the constant traffic. I felt slightly betrayed, the man with the scales and I had known each other for several years. What upset me most was that he seemed to enjoy his communication with the new resident and was smiling after she had left him. As I hurried across I smiled at the scalesman, an enormous smile, a smile larger than any smile I have produced before or since. A smile performed entirely to impress the bathroom scalesman with my friendliness. He did not look up, he was smiling to himself, looking at his notebook.