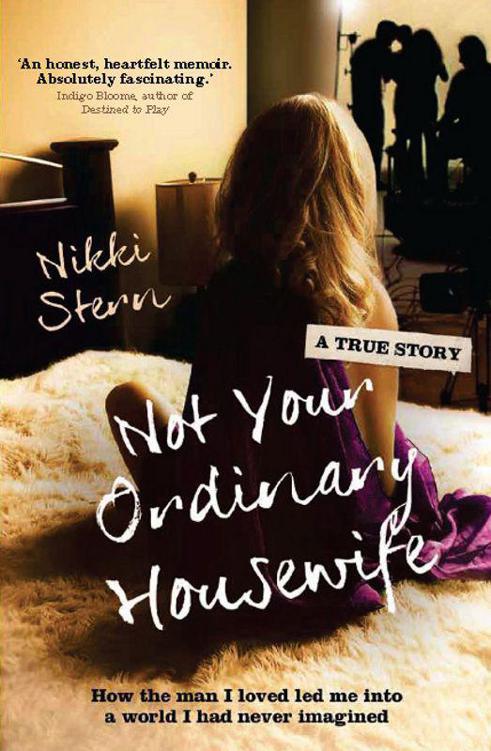

Not Your Ordinary Housewife: How the man I loved led me into a world I had never imagined

Authors: Nikki Stern

Tags: #book, #BIO026000

Author photograph: Viana Van Eyk

Nikki Stern was born in Sydney but raised in Melbourne by Holocaust survivors. Educated at MLC, she later attended Monash University, earning degrees in science and design, plus a postgraduate diploma in psychology. After working as a glass artist in Adelaide she travelled to Europe, settling in Amsterdam where she met her husband, Paul Van Eyk. Returning to Australia, they operated the

Horny Housewife

X-rated video business out of Canberra, which saw the couple produce and star in the bestselling

Horny Housewife

movies—now in the Australian National Film and Sound Archive.

Nikki currently lives with her children and works as a librarian. In her spare time she indulges her passions of books, music and art.

How the man I loved led me into

a world I had never imagined

All efforts have been made to obtain permission to reproduce copyrighted material in this book.

In instances where these efforts have been unsuccessful, copyright holders are invited to contact

the publisher directly.

First published in 2012

Copyright © Nikki Stern 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian

Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

| Phone: | (61 2) 8425 0100 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| Web: | www.allenandunwin.com |

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 339 8

Set in 13/17 pt Granjon by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my three beautiful children (they know who they are)

And my four parents:

Dory Stern

Egon Stern, AO

Gertrude Farmer

Allan Proctor, DFC

‘Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.’

Act IV, Scene II, Cymbeline,

William Shakespeare

Contents

The news reports were using phrases like ‘freak weather event’ to describe the red dust storm that enveloped Melbourne one afternoon in February 1983. When it struck, I was delivering a consignment of my glass sculptures to a gallery in Hawthorn. Luckily, it was the last stop on my list. As I stood trapped inside—the lack of visibility preventing me from driving the short distance home—I thought again of the trip I was about to take. My plan was to spend a year doing art while wandering the great galleries of Europe. I was itching for adventure and would let destiny decide my fate.

Lately, I had found myself in a career cul-de-sac. After completing an art and design degree majoring in glass studies, I had spent a year at Adelaide’s artisan paradise, the Jam Factory Craft Centre, a heritage building that housed a gallery and numerous craft workshops, including a world-renowned glass studio. Participating in several group exhibitions, I had earned the moniker of emerging glass artist but then I developed pterygia—a nasty eye condition exacerbated by the heat of the furnace. As a result, I had decided to change trajectory—henceforth I would concentrate on works on paper: ink drawings in my distinctive cartoon style, collage and photography.

I stayed briefly with my mother in Melbourne before heading off. Dory’s beloved Egon—her husband of 50 years and my adoring father—had recently died and she was bereft. As their only child, I had always been the focus of her overbearing Jewish angst. She harassed me mercilessly, distressed by my appearance. In her eyes, I seemed too alternative, bordering on punk, whereas I saw myself as merely arty alternative. My dark hair was partly dyed blonde and I wore predominantly black and white. I guess when I thought about it, she was right—there was definitely an element of edginess about me.

With Amsterdam as my base, my aim was to find a new artistic direction. Backpacking would allow me to drift, away from the grip of my overanxious mother. I could survive for a year on my savings—the Aussie dollar was at an all-time high and living would be cheap if I was careful.

On the day of my departure, Dory extracted a promise from me to write regularly. At the same time, she stuffed into my address book a sheet of paper containing dozens of phone numbers.

‘You might need these in an emergency,’ she said in her thick Viennese accent.

I scanned her parting gift. It was a neatly written alphabetised list of countries, each with a number of contacts. Many I knew from my childhood—artists, musicians and dancers. Perhaps it was because she had lost nearly all her family in the Holocaust that Dory had a plethora of close friends. Her empathy for the suffering of fellow human beings endeared her to a vast array of people. She was a person with high ethical standards, not in a religious sense—for she was atheist—but in a humanist sense.

‘I can’t just call these people up and come and stay,’ I explained. ‘Like, for instance, the Countess of Harewood . . .’

‘Well, I’ve given you her townhouse address, not Harewood House. I’ve stayed there a few times—it’s basically a palace. Turner painted it. It’s open to the public now, you know?’

‘Well, I’ll take the phone number, just in case, but I have all my glassblowing contacts. Anyway, I’m going to be staying in youth hostels, or sleeping on the train . . .’

‘You never know what might happen.’

Dory was often full of pessimism. Escaping Hitler had taught her that. Why couldn’t she say ‘Have a wonderful time, just be careful,’ like an ordinary Australian mother would? In the end, we argued over trivialities and I left without saying goodbye.

Quite quickly, my memory of our parting faded as I flew towards Europe. I knew I would have no trouble meeting people. One of the subtle skills Dory had bestowed on me was her amazing ability to strike up an acquaintance with strangers. She could make friends in unlikely places; people were attracted to her ebullience. I too could be like that, talking easily with most people.

I first landed in Rome and wandered its streets, soaking up the ambience. People stared at me with my dyed hair and new-wave clothing. I roamed the corridors of the Vatican, overwhelmed by the beauty of the art, all the while remembering Egon telling me how the Vatican officials helped so many Nazis escape to South America after the war. At the gift shop there, I bought two diaries—one to record my experiences, the other to document the galleries I would visit as I criss-crossed Europe on my rail pass.

I was keen to see Vienna, because of its deep significance in my life. My parents had fled just days before Hitler’s annexation, leaving behind everything: family, friends and property. It had always been a subject far too painful for direct conversation, and there was inevitably the tragic subtext that accompanied any mention of the Holocaust. Neither Dory nor Egon had been able to visit Vienna for many decades; when they finally did they said little on their return.

Vienna’s giant Ferris wheel at the Prater had dominated the physical landscape of Dory’s childhood. I took the ride, and from its summit I looked around me and wondered which of the tiny houses below had been hers and how I could ever comprehend her life here. I bought her a postcard featuring the wheel. Because it symbolised her lost life, I knew that she would see the photo and weep. She often shed tears, but now as I tried to write, I was doing so too. I was stuck for words and I could not adequately express the emotions I was feeling.

I knew I needed to be more tolerant of Dory’s neuroses. Her pathological over-protectiveness of me was a result of her unimaginable loss. But crying was something I almost never did. I theorised that it was because I had been in an orphanage for my first eight months and that babies in that situation soon learned the futility of tears. It was not that I didn’t feel emotion—for I plainly did—but I rarely expressed it overtly.