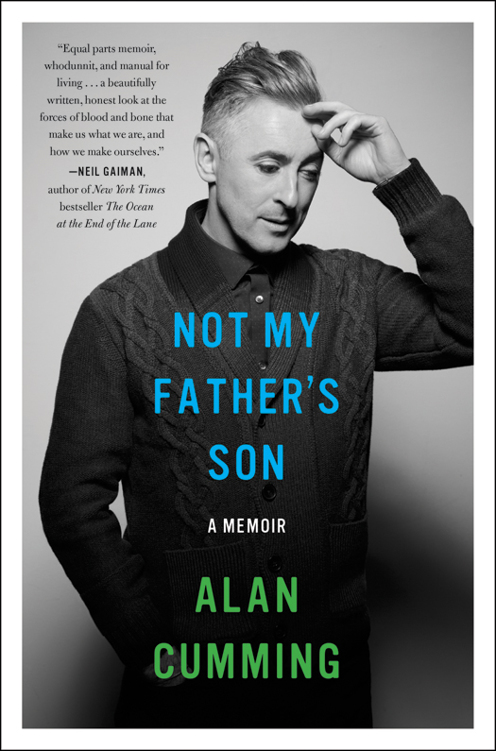

Not My Father's Son

Read Not My Father's Son Online

Authors: Alan Cumming

FOR MARY D, THE TWO TOMS, AND GRANT SHAFFER

Y

ou need a haircut, boy!”

My father had only glanced at me across the kitchen table as he spoke but I had already seen in his eyes the coming storm.

I tried to speak but the fear that now engulfed me made it hard to swallow, and all that came out was a little gasping sound that hurt my throat even more. And I knew speaking would only make things worse, make him despise me more, make him pounce sooner. That was the worst bit, the waiting. I never knew exactly when it would come, and that, I know, was his favorite part.

As usual we had eaten our evening meal in near silence until my father had spoken. Until recently my older brother, Tom, would have been seated where I was now, helping to deflect the gaze of impending rage that was now focused entirely upon me. But Tom had a job now. He left every morning in a shirt and tie and our father hated him for it. Tom was no longer in his thrall. Tom had escaped. I hadn’t been so lucky yet.

My mother tried to intervene. “I’ll take him to the barber’s on Saturday morning, Ali,” she said.

“He’ll be working on Saturday. He’s not getting away with slouching off his work again. There’s too much of that going on in this house, do you hear me?”

“Yes,” I managed.

But now I knew it was a lost cause. It wasn’t just a haircut, it was now my physical shortcomings as a laborer, my inability to perform the tasks he gave me every weekend and many evenings, tasks I was unable to perform because I was twelve, but mostly because he wanted me to fail at them so he could hit me.

You see, I understood my father. I had learned from a very young age to interpret the tone of every word he uttered, his body language, the energy he brought into a room. It has not been pleasant as an adult to realize that dealing with my father’s violence was the beginning of my studies of acting.

“I can get one tomorrow at school lunchtime.” My voice trailed off in that way I knew sounded too pleading, too weak, but I couldn’t help it.

“Yes, do that, pet,” my mum said, kindly.

I could sense the optimism in her tone and I loved her for it. But I knew it was false optimism, denial. This was going to end badly, and there was no way to prevent it.

Every night getting off the school bus, walking through the gates of the estate where we lived, past the sawmill yard where my father reigned, and towards our house was like a lottery. Would he be home yet? What mood would he be in? As soon as I entered the house and changed out of my school uniform and began my chores—bringing wood and coal in for the fire, starting the fire, setting the table, warming the plates, putting the potatoes on to boil—I felt a bit safer. You see, by then I was on his territory, under his command, I worked for him, and that seemed to calm my father, as though my utter servitude was necessary to his well-being. I still wasn’t completely safe of course—I was never safe—but those chores were so ingrained in me and I felt I did them well enough that even if he did inspect them I would pass muster, so I could breathe a little easier until we sat down to eat.

My father was the head forester of Panmure Estate, a country estate near Carnoustie, on the east coast of Scotland. The estate was vast, with fifty farms and thousands of acres of woodland covering over twenty-one square miles of land. We lived on what was known as the estate “premises,” the grounds of Panmure House, though by the time we lived there the big house was long gone. In 1955, as one of many such austerity measures forced upon the landed aristocracy, its treasures were dismantled and then explosives razed it to the ground. All that remained were the stables, where on chilly Saturday mornings during hunting season I’d report, banging my wellies together to keep the feeling in my toes, to work as a beater, hitting trees with a stick in a line of other country boys, scaring the birds up into the air so that drunk rich men could shoot at them.

Attached still to the stables was the building that had been the house’s chapel. Now it was used for the annual estate Christmas party and occasional dances or card game evenings for the workers. We lived in Nursery House, so called because it looked out on a tree nursery where seedlings were hatched and nurtured to replace the trees that were constantly felled and sent back to the sawmill that lay up the yard behind us. My father was in charge of the whole process, from the seeds all the way to the cut lumber and everything in between, as well as the general upkeep of the grounds.

It was all very feudal and a bit

Downton Abbey,

minus the abbey and fifty years later. I answered the door to men who referred to my father as “The Maister.” There were gamekeepers and big gates and sweeping drives and follies but no lord of the manor, as during the time we lived there the place was owned by, respectively, a family shipping company, a racehorse owner’s charitable trust, and then a huge insurance company.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was living through the end of an era of grand Scottish estates, as now, like Panmure, they have been mostly all dismantled and sold off. Looking back on it, it was a beautiful place to grow up, but at the time all I wanted was to get as far away as possible.

I had seen my father’s van parked by the tractor shed as I walked by. So he was home. But maybe he wasn’t actually in the house, maybe he was talking to one of his men in the sawmill or in one of the storehouses or sheds. It was the time of day when they were coming back from the woods and cleaning their tools before going home. I couldn’t see my dad, although I didn’t want to be seen to be looking for him in case he spotted me and he’d know that my fear was guiding my search. That would be his opening. Maybe there would be someone in the yard who’d come to see him, a farmer or even his boss, the estate factor (or manager), who would allow me to get by him without inspection.

I turned round the corner into the driveway of our house at the bottom of the sawmill yard, and I could see there was a light on in his office. My heart sank. He was sitting at his desk in the window and he looked up when he saw me. Immediately I straightened, tried to remember all the things he’d told me were wrong about me recently. I prayed my hair was combed the way he liked it, my school bag was hanging on my shoulder at the right angle, and my shoes were shiny enough. It probably took only ten seconds before I reached the front door and was out of his sight, but in that flash a myriad of anxieties about my flaws and failures had whirred across my mind.

He was on the phone, thankfully. He didn’t come out of his office even until after my mum came home from work, and I always felt a little lighter having her in the house. She finished making our tea while we chatted. Then we heard the noise of him approaching through the house towards us and we were quiet. We both knew it was not a good idea to speak until we had appraised him, and tonight apparently it was not a good idea to speak at all.

My father sat into his chair at the kitchen table and immediately my mother set down his plate of food in front of him. This is how it always happened. Any deviation, let alone any complaint about the food, could start him off. Without acknowledging her or me he lifted his cutlery and began to eat. He ate like an animal, not because he was messy or noisy, but because he

tore

at his food, with strength and stealth and efficiency. It was terrifying to watch.

My father was silent for a while after my mum spoke, and I hoped that my going to the barber’s during school lunch break the next day would appease him. All I could think of was getting to the end of this meal and upstairs to my homework, or better yet far into the woods with my dog to hide. But my mouth was so dry, and there was a lump of fear stuck at the top of my chest that made it hard to swallow. I had to get some water or I was going to choke, or worse, cry. I got up from the table and moved towards the sink. I picked up a glass off the draining board and began to fill it.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?” he said, not quite shouting yet, but still too loud, as though he had been waiting to say it, eager to make the next move, and now here it was.

“Eh? Did you hear me?”

“I need to drink some water,” I gasped.

“Put that glass down!” Now he was shouting.

My mother said very quietly, “Ali, leave him.”

My father rose from his chair and everything went red. At the same time as he began shouting at me he grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and I was being dragged across the kitchen, through the living room, through the hallway, out through the porch and the front door and across the yard to the shed where we kept our bikes. He threw me up on top of a workbench. He was

baying

now, not just shouting. You couldn’t understand what he was saying but I know it had to do with my hair and my water drinking and how fucking useless and insolent and pathetic I was, but it wasn’t coherent. It was just pure violent rage, and it was directed at me.

There was a lone bare lightbulb hanging from the shed ceiling. I remember looking up at it as he scrambled in a drawer behind me. Soon my head was propelled forward by his hand, the other one wielding a rusty pair of clippers that he used on the sheep we had in the field in front of our house. They were blunt and dirty and they cut my skin, but my father shaved my head with them, holding me down like an animal.

I was hysterical now, as hysterical as he was, but I knew he enjoyed hearing me scream and it would be over quicker if I was quiet and limp. But that was so hard. I was in pain and shock and I still hadn’t had a drink of water and I felt I was going to pass out with trying to catch my breath. All I could do was wait for the end. Eventually it was over. He pushed my head one way, then the other in order to inspect his work, then threw the clippers back in the drawer.