Not Bad for a Bad Lad

Read Not Bad for a Bad Lad Online

Authors: Michael Morpurgo

THIS IS THE STORY of my life. I’ve written it so you’ll know all the things about your grandpa that you’ve got a right to know and that I never told you. There’s no two ways about it: when I was young I was a bad lad. I’m not proud of it, not one bit. Grandma has been saying for quite a while now that it’s about time I told you everything, the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth – before it’s too late, she says. So here goes.

I was born in 1943, on the 5th of October. But you don’t want to know that. It was a long time ago, that’s all, when the world was a very different place. A whole lifetime ago for me.

I had a dad, of course I did, but I never met him. He just wasn’t there, so I didn’t miss him. Well maybe I did, maybe I just didn’t know it at the time. Ma had six children. I was number four and I was

always

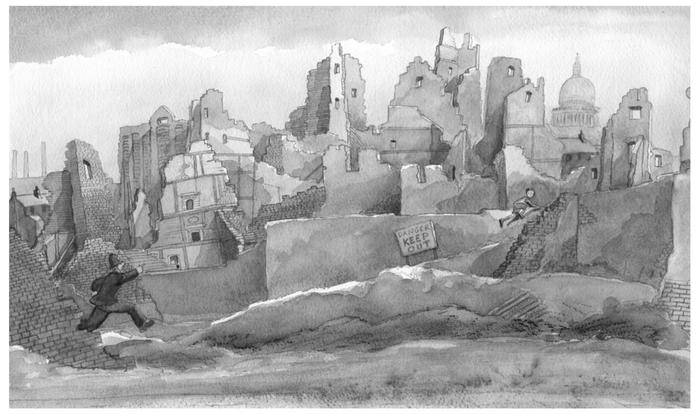

a bad lad, right from the start. Down our street there was this bomb site – there were lots of houses around us all bombed to bits in the war. There was a sign up outside the bomb site. It said: ‘Danger. Keep Out’. Well of course I went in, didn’t I? And that’s because it was the best place to play. I’m telling you, it was supreme. I could climb the walls, I could make

dens, I could chase butterflies, and when Ma called me in for my tea I could hide away and pretend I wasn’t there. I remember the local copper. He was called PC Nightingale – some names you don’t forget – and he would come in after me sometimes and chase me out. He’d shout it out all down the street how he’d give me a right good hiding if he ever caught me in there again.

When I was old enough to go to school, to St Matthias, down the road, I discovered pretty quick that I didn’t like it, or they didn’t like me – a bit of both, I reckon. That’s why I bunked off school

whenever

I could, whenever I felt like it, which was quite often. The School Attendance Officer would come round to the house and complain to Ma about me.

Sometimes he’d threaten to take me away and put me in a home, then Ma would get all upset and yell at me, and I’d yell back at her. We did a lot of yelling, Ma and me. I’d tell her how the teachers were always having a go at me, whatever I was doing, whenever I opened my mouth, that they whacked me with a ruler if I talked back, or cheeked them, that I spent most of my lessons standing with my face in the corner, so what was the point of being at school anyway?

The trouble was, and I can see now what I couldn’t see then, that I turned out to be no good at anything the teachers wanted me to be good at. And when I was no good they told me I was no good, and that just made the whole thing worse. I couldn’t do my reading. I couldn’t do my writing. I couldn’t do my arithmetic – sums and things like that. I was, “a brainless, useless, good-for-nothing waste of space”.

That’s what Mr Mortimer called me one day in front of the whole school and he was the head teacher, so he had to be right, didn’t he? There was only one thing I did like at school and that was the music lessons, because we had Miss West to teach us and Miss West liked me, I could tell. She was kind to me, made me feel special. She smelled of lavender and face powder and I loved that. She made me Drum Cupboard Monitor, and that meant that whenever she wanted anything from the drum cupboard, she’d give me the key and send me off to fetch a triangle, or the cymbals maybe, or the tambourines, or a drum. And what’s more, she’d let me play on them too. So when all the others were tootling away on their recorders, I got to have a go on the drums, or the cymbals, or the tambourine, or the triangle – but the triangle was a bit tinkly, didn’t make a loud enough noise, not for me anyway. I liked the drum best. I liked banging out the

rhythm, loud, and Miss West told me I had a really good sense of rhythm, that drums and me were made for one another, even if I was sometimes, she said, “a wee bit over-enthusiastic”.

Then Miss West left the school – I don’t know why – and that made me very sad. I still played the drums whenever I could, and I was still Drum

Cupboard

Monitor, but none of it was nearly so much fun without Miss West. I never forgot her though, and

you’ll see why soon enough.

I was that keen on drumming by now that I began to find ways of doing it out of school. At home I’d play the spoons all the time, and drive Ma half barmy with it. When she sent me out, I’d do it with sticks on the railings, or on dustbin lids. Dustbin lids were best

because

if I banged them hard enough I could make a din like thunder that echoed all down the street, and sent the pigeons scattering.

Some people, like Mrs Dickson who kept the shop on the corner, had two dustbins outside, so I could stand there and bang away on two dustbin lids at the same time, then I could pick them up and crash them

together

like cymbals. You should have heard the racket that made! But Mrs Dickson was a bit of a spoilsport. She’d come running out of her shop and tick me off. She’d shoo me away with her broom, and call me “a bad, bad lad” – and other things too that I’d better not mention.

Then I went and did something really stupid.

I stole an orange from a barrow in the market. And what did I do? I only ran round the corner, smack into PC Nightingale, who also told me I was a bad lad. He took me back home, tweaking my ear all the way, and told Ma what I had done, and that I needed a right good walloping. So she said I was a bad lad too and smacked me on the back of my knees. The day after that, things only went from bad to worse.

In school the next morning, at assembly, Mr

Mortimer

told us he’d got a very serious announcement to make, very serious indeed. He said that PC

Nightingale

had been in to see him with some very bad news, about an orange. I knew I was in for it now. He held up the orange I’d nicked, or one just like it, and told everyone that they had an orange thief in the school. I knew what was coming. He called out my name and pointed right at me with his yellow nicotiney finger. Everyone turned round to look at me, which I didn’t much mind – actually, to be honest, I quite enjoyed that part of it – you know, the fame part, the

recognition

. After all, I was the school’s chief troublemaker. That was what I was good at, being a troublemaker. I was proud of it too. I had my reputation. I was

someone

to be reckoned with and I liked that.

Mr Mortimer got me up there in front of everyone, and told me to hold out my hand, and then he whacked me with the ruler – which I did mind,

because

this time it was with the edge of the ruler, on the back of my hand, on my knuckles, and it hurt like billy-o. And, yes, you’ve guessed it, he told me I was a bad lad, and how I’d bought shame on myself and on the whole school.

Worst of all though, he said I wasn’t Drum

Cupboard

Monitor any more, and that I wasn’t going to be allowed to play on the drums any more, nor on the cymbals, nor even on the silly triangle, not ever. Well, that was it, the final straw, that and my bruised knuckles. Now I was mad, really mad – and I’m not excusing myself – but that was why I went and did something that was even more stupid than nicking the orange in the first place.