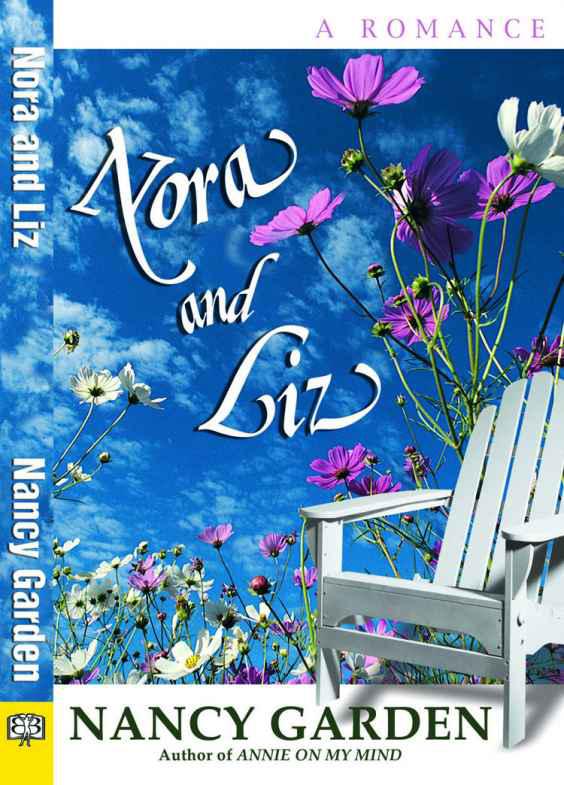

Nora and Liz

Authors: Nancy Garden

Tags: #Gay & Lesbian, #Fiction, #Lesbian, #General, #Espionage

- About the Author

- Book I

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Book II

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- Chapter Twenty-Two

- Chapter Twenty-Three

- Chapter Twenty-Four

- Book III

- Chapter Twenty-Six

- Chapter Twenty-Seven

- Chapter Twenty-Eight

- Chapter Twenty-Nine

- Chapter Thirty

- Chapter Thirty-One

- Chapter Thirty-Two

- Chapter Thirty-Three

- Chapter Thirty-Four

- Chapter Thirty-Five

- Chapter Thirty-Six

- Chapter Thirty-Seven

- Chapter Thirty-Eight

- Chapter Thirty-Nine

- Book IV

NORA & LIZ

BY

NANCY GARDEN

Copyright © 2002 by Nancy Garden

Bella Books, Inc.

P.O. Box 10543

Tallahassee, FL 32302

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First Edition 2002

Second Printing 2004

Third Printing 2012

Cover designer: Bonnie

Liss

(Phoenix Graphics)

ISBN: 13-978-1-931513-20-3

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Nancy Garden is the author of around 30 books for children and teens, a number of which feature gay and lesbian characters and issues. Her young adult novel,

Good Moon Rising,

was a Lambda Book Award winner and her highly acclaimed

Annie on My Mind,

burned, banned, and tried in Kansas, is listed by the American Library Association as one of the 100 Best of the Best Books for Young Adults.

A former editor and pre-Stonewall activist, in addition to working on her own books, Nancy today teaches writing and speaks around the country to librarians, teachers and lay people against censorship and in support of GLBT youth. She and her partner of 33 years divide their time between Massachusetts and Maine.

For Sandy,

my sine qua non

And with thanks to Detective Nancy

Iosue

of the Carlisle, Massachusetts, Police Department, who advised me about procedural matters. Any errors are mine, not hers.

Chapter One

It was dim in the kitchen. The sun slanted through the window over the dark sink, picking up dust motes, but Nora

Tillot

did not allow herself to dwell for long on the joy of their dancing. As her hand curled around the green pump handle, sending a stream of cold water into the pitted aluminum kettle and then into the oversized iron pot, her motions were that of an old woman, slow, careful, deliberate. But at forty, Nora was hardly old, though her face was lined and her dark blond hair, caught up in a severe bun, showed streaks of gray.

She bent to pat the small black and white cat that was curling himself around her ankles, purring, and filled his dish with kibble from the box beside the sink. “There, Thomas,” she said absently, “sweet kitty.” She knelt in front of the iron

cookstove

to open the oven, and blew on the glowing coals till they flared. “Careful,” she could remember her father saying authoritatively around the panatela clamped between his teeth. “Careful. You’ll singe your hair.”

Back then, her usual rejoinder on days when she felt defiant had been, “What about you with your infernal cigars?” But no one smoked any more in the old farmhouse whose clapboards were rotting and whose walls sagged inward, not Corinne, Nora’s invalid mother, and certainly not her eighty-five-year-old father, semi-bedridden for years with what the doctor called “hypochondria, depression, and God knows what.” Ralph

Tillot

was a disappointed, penny-pinching man who had never managed to make much of himself, despite the “friends in high places” of whom he had often bragged, sometimes at the expense of his one or two actual friends.

Nora lifted the kettle and the pot onto the stove, after opening two of its “burners”—holes that would be called burners, anyway, on a modern stove like the one Louise Brice, who took Nora to the grocery store on Fridays and to church on Sundays, kept saying Nora should buy despite her father’s objections. “And electricity and plumbing and a telephone,” Mrs. Brice said almost every week, chipping away at Nora’s resolve to keep peace with her parents. “At least a telephone. It’s not safe, dear, you alone in this firetrap of a house with two old people. What if your mother has another stroke?”

“Then I’ll do what I did before,” Nora had said doggedly last time. “Run to the neighbors’ and call from there.”

“That’s a half-mile run,” Louise Brice said dryly, “to the

Lorens

’ house, and you’re no athlete.”

Nora turned back to the sink, smiling briefly at the memory as she let the cat out. She’d long since stopped explaining to Mrs. Brice and to the minister, the Reverend Charles Hastings, that the way she and her parents lived was, after all, not unlike the way many people had lived as recently as eighty or so years earlier, and certainly the way her father’s forebears had lived when they’d built the house in the late eighteenth century. People had managed then, so why not now? That was one of her father’s arguments, and Nora, when she was challenged, borrowed it defensively, though when she let herself, she longed for electricity, a refrigerator instead of an ice box on the back stoop, an indoor bathroom instead of an outhouse, a furnace, a modern stove, a telephone.

Oh, especially a telephone, she thought, moving the pile of galley proofs—Nora proofread for pin money—away from the rusty canister under the window and spooning loose tea into the everyday brown pot. Mrs. Brice is right about that. And young Patty Monahan—Nora smiled to herself once more—who sat with her parents while Nora was at church or out shopping, had widened her eyes in obvious shock the first time she’d come, clearly more startled at the absence of a phone than at the lack of electricity and running water.

But Ralph wouldn’t hear of it.

After her solitary cup of tea, sipped slowly at the scarred pine table opposite the sink while she watched the sun rise wearily over the woods that edged the back field, Nora enveloped her slender body in a huge coverall apron made of plain unbleached muslin, which she’d found was best for the bathing ritual. That involved pans and pitchers and basins of water, carried to her parents’ bedsides along with sponges, washcloths (“flannels,” Mama had called them before her stroke, as in English books), plus soap (pink geranium for Mama, tan sandalwood for Father), and towels. At least this task, the most odious of all, usually came early in the day.

Grimly, Nora smoothed down the apron, knotted it around her waist, and ladled hot water from the steaming pot into a white enamel basin, then added cold via a saucepan carried from the sink pump. Draping a clean white towel and a blue “flannel” over her arm, and carefully balancing the basin plus the bowl into which she’d poured her father’s shaving water, Nora went into Ralph’s room off one end of the kitchen. Corinne’s was off the opposite end, so both rooms were able to absorb some of the heat from the

cookstove

. Even in winter Nora rarely lit its potbellied companion, isolated in the largely unused parlor; life in the

Tillot

household had always centered around the kitchen, and had done so almost exclusively since Nora’s parents had entered old age.

“Morning, Father,” Nora said cheerfully. “Want the urinal before your bath?”

Ralph

Tillot

, so far a lump under the threadbare green blanket and patched patchwork quilt (although it was warm for late May in Clarkston, Rhode Island), grunted noncommittally, so Nora unhooked the curved plastic bottle from the headboard and handed it to him.

“Umm,” he grunted, taking it and sliding it under the covers.

“You’re welcome,” Nora said, and went to the window, pulling up the yellowing shade. It snapped out of her hand and flapped, making a whirring noise.

“Jesus Christ almighty,” her father bellowed, holding the used urinal out to her. “Watch what you’re doing, can’t you?”

“Sorry,” Nora said evenly. “It slipped right out of my hand.”

“Well, watch that this doesn’t slip, too,” he growled, shoving the urinal at her. “No, wait,” he said as she took it and turned away. “Any blood in it?”

“Blood?” Nora asked, surprised; this was a new worry.

“You heard me; blood. It’s painful,” he whined.

“What is?” Nora peered down the spout. She couldn’t really see, but the urine seemed its normal early-morning color.

“Pissing.”

“I’m sorry, Father.” She stroked his arm briefly. “Want me to tell Dr. Cantor?”

Her father pulled himself up to a sitting position. “Is there blood?”

“Not that I can see.”

“Well, let’s keep an eye on it. Go ahead and dump it.”

“I’ll just put it here"—Nora hooked it over the back of a chair—“till I finish your bath. Otherwise the

water’ll

get cold.”

Her father said something that sounded like “

Erumph

,” so Nora, taking that for assent, unbuttoned his pajama top (he wore no bottoms), and slowly sponged him. He lay quietly, unmoving, as she passed the warm, dampened cloth over his flaccid body, till she told him to turn. The sheets were dry, thank God (he often wet the bed), so if she was careful she wouldn’t have to change them or have the argument they frequently had about his wearing Depends at night, as did his eighty-two-year-old wife.

After she’d dried and powdered him, she shaved him, then laid out underwear, shirt, and pants. But he waved them away as he frequently did these days. “Not yet,” he said, making kissing motions with his mouth. “Maybe later. You’re a good girl, Nora. A nice girl. You take good care of your old father. I love you.”

“I love you, too,” she said automatically, grateful that all signs pointed to its being a calm day, at least as far as Ralph was concerned. “I’ll bathe Mama and then I’ll get your breakfast. Think about what you’d like.”

“Just toast,” he said as he always did. “And coffee.”

“Coming right up,” she said cheerfully. “After Mama’s bath.”

Giving him a little wave, she went back to the kitchen, dumped his bath and shaving water, and poured fresh for her mother. Too late, she remembered the urinal, so she poured her mother’s water into the pot again and returned for the urinal.

“I feel dizzy,” Ralph whined when she’d emptied and rinsed it, and brought it back.