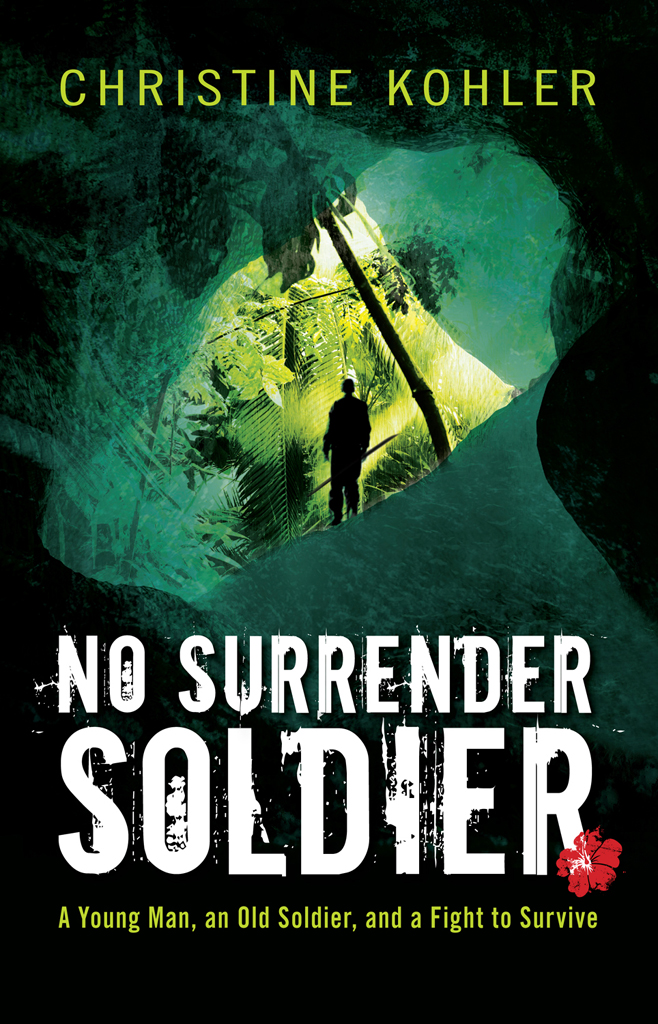

No Surrender Soldier

Read No Surrender Soldier Online

Authors: Christine Kohler

SOLDIER

CHRISTINE KOHLER

F+W Media, Inc.

F+W Media, Inc.

Chapter 2: No Surrender Soldier

Chapter 18: M.I.A. In the Jungle

Chapter 27: Seto’s Last Days on Guam

Chapter 28: Beyond the Horizon

The purpose of this glossary is to familiarize you with terms of address in the Chamorro culture. Chamorros are descendants of indigenous Pacific Islanders in the Marianas who inter-married with Spanish sailors. Their language is a mixture of Chamorro and Spanish. Since the United States acquired Guam as a result of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Guamanians—Chamorros included—speak English. Still, their terms of address are Chamorro.

nana

(nan-a)—mother

nana bihu

(nan-a bi-who)—grandmother

tata

(ta-ta)—father

tatan bihu

(ta-tan bi-who)—grandfather

tan

(tan)—aunt

tihu

(tee-who)—uncle

GUAM

WORLD WAR II, JULY 21, 1944

Planes swarmed over Guam in droves. For a moment Lance Corporal Isamu Seto thought he was home in Japan. He was washing his face in the Talofofo River when he heard buzzing sounds. He looked up into the overcast sky and thought locusts were coming to destroy crops in his village of Saori. He blinked and shook his head.

Aiee, angry locusts turn into bombers. Amerikans must be attacking.

Seto threw his field hat on and snatched up his rifle. No time to worry about filling his canteen or fetching his knapsack. Besides, if things did not go well in battle, Seto knew what his superiors required of him. To die honorably, and go the way of the cherry blossoms. He looked at the bayonet on the end of his rifle and swallowed hard against what felt like a peach pit stuck in his throat. He had pledged to die in battle for Emperor Hiro Hito. But could he commit

hara-kiri

like a true samurai?

Pain throbbed in his head. He did not want to think of such things. He must join his comrades and go to the mountains to ward off the enemy. Seto jogged upstream to find the soldiers, who were drinking

sake

, squabbling over a can of salmon, and eating three-day-old rice. He ignored the rumbling of his stomach. No time to break his fast—he kept his eyes on the bombers overhead.

Ka-boom, ka-boom!

Shells dropped in the distance. Fire exploded upward from the earth. Seto ducked as if the bombers aimed directly at him. The soldiers scattered. Seto felt responsible for his comrades since they were young and of lesser rank. He ran, calling for his men. Private Yoshi Nakamura leapt up from the above-ground roots of an evil spirit tree. Private Michi Hayato crawled out from behind a rock. They joined Seto, climbed the cliff, and ran toward the mountain.

Once together, they hung back at the base of the mountain. They crouched behind scraggly brush and waited. Planes continued to swarm and drop bombs.

Ka-boom, ka-boom!

Shells exploded—closer, closer. Smoke and the smell of sulfur filled the air. Rifle loaded, eyes fixed high above the ridge, Seto trembled. He waited for the

Amerikans

.

The sun seared through the sky, hazy from bombs exploding. It sounded like thunder as tanks rumbled over the mountain crest. Closer, closer tanks roared. US Marines advanced. Plumes of dust, shellfire, and rifle blasts clouded the air. When it cleared, Seto saw in the distance fellow Japanese soldiers lay dead. Those who did not die by enemy gunfire spilled their guts onto the ground with their bayonets. Some Japanese soldiers unpinned grenades under their helmets, and bloody, headless bodies remained.

Seto retched. His gun was no match for tanks and marines. Their numbers were too great. And his fellow soldiers too quick to die. He spit out the bile taste in his mouth. Tanks rolled over the crest and down the mountain toward Seto and his men. They ran.

Down the mountain, over the cliff, under the waterfall, into the river, through the mosquito-infested jungle, they ran.

Too many Amerikans storming the island. Too many Japanese dead,

pounded through Seto’s head as sweat streamed out from under his helmet.

Once in the jungle the soldiers stopped to catch their breaths. Seto listened. Gunfire and bombs burst in the distance. The men looked to Seto for a decision.

He wiped his mouth. “We wait.”

That steamy, bloody day in 1944 when Americans stormed the island of Guam, the moment had come. Seto’s moment of decision. Should he charge back over the mountain and face the US Marines with his rifle and bayonet? Or should he be done with it? He would disembowel himself like a true samurai.

If he did neither, Seto knew he would shame his family name, bring shame to the emperor and Japan. His head throbbed at this moment of decision. Bile rose in his throat.

Privates Nakamura and Hayato asked again, “

What do we do? The Amerikans are near!

”

Seto listened to the

rat-a-tat-tat

of guns. He smelled gunpowder and the smoke of cannon shells exploding.

He trembled inside. Seto decided one thing and one thing only. “I vow never to surrender.”

CRAZY TATAN

GUAM, JANUARY 3, 1972

Before my grandfather, Tatan Bihu San Nicolas, lost his mind, he called me “Little Turtle.” Ancient Chamorros believed our island was borne on the back of a turtle that settled down in the Mariana Trench. I wanted to believe that “Little Turtle” was my grandfather’s way of saying I was steady, strong like the turtle. He would say the turtle that birthed Guam spit me out onto the beach. Then, in his tough-guy way, Tatan would say, “You no taste good,” and laugh his fool head off.

Come to think of it, maybe Tatan was crazy before old age robbed his memory.

I’ve wished I was a turtle for real since my older brother, Samuel Christopher Chargalauf, went off to fight in Vietnam. I wish I could swim from our island of Guam across the Pacific Ocean to Southeast Asia and bring my brother back.

Sammy being gone is killing my mother. Nana’s brown almond eyes are red-rimmed from crying herself to sleep every night. I know, I hear her through the bedroom wall, sobbing as if she has hiccups that won’t stop. My father stands around looking like he’s in pain most the time. Like someone has a knife twisted in his gut and he’s too stunned to pull it out. Seeing my family falling apart is making me feel as lost as Sammy and as crazy as Tatan.

But, looking back, if I had to pick a day when my world unraveled, I’m not sure it would be when Sammy left for war, or when Tatan lost his mind.

No, as horrible as those days were—what I thought of as the worst days of my life—it got worse. It got so bad I didn’t even know myself. Didn’t know how mean and evil and rotten to the core I could be. How crazy I could get. Crazy enough to want to kill a man.

It all started like any other day at my family’s tourist shop, Sammy’s Quonset Hut, which is named after my brother. It isn’t really a Quonset building, rather a regular storefront a block from Tumon beach, which is like Waikiki on Oahu where all the tourists stay. My parents were sad and mopey about Sammy being overseas. I admit, I was p.o.ed, too. Christmas break was nearly over. I’d told my buddy, Tomas Tanaka, I would meet him at the beach. But instead I was ramming a dull box cutter back and forth into cardboard. Before my father left with a deposit for the bank, he’d told me I couldn’t go to the beach until the shelves were stocked.

“If I had the Swiss Army knife Tata gave Sammy, I could open these boxes as easy as slicing mangoes with a machete.” I was sorry I said it the minute it came out of my mouth. It was a good thing my father wasn’t back from the bank yet or else he would have chewed me out for saying such a thing.

Nana looked up from cleaning a display case. Hurt shone all over her moon-shaped face. “Your tata knew what he was doing. Sammy needs that knife more than you do.”

Shoving plastic-wrapped seashells on a shelf, I cracked open the top of a wooden crate from the Philippines and choked back coughs. I don’t know what that straw-like packing stuff’s made of, but the smell always makes me cough and my nose run. I pulled it off and reached into the crate.

Nana let out a pitiful laugh as if she was trying too hard to cheer me up. “Pretty pathetic when we import these.” It wasn’t working. Like I said, I was p.o.ed.

I held up a coconut decorated like a goofy shrunken native head and grunted. “You talking about coconuts or empty heads?” I chucked my chin toward Tatan, hunched over the counter doing nothing. He used to be tall and thick like an Ifil tree. But it was as if overnight his trunk buckled and branches bent under an invisible weight. My grandfather’s weathered walnut face rarely smiled anymore, his mood always sour.

I shook the coconut. “We would’ve had this shipment unpacked weeks ago if it weren’t for him.”

“Hold your tongue.” Nana shook her finger at me. “At fifteen you know everyt’ing? You don’t. I won’t have you disrespect your tatan bihu.”

Ding, ding, ding.

The bell over the door signaled for us to stop, like at the end of a round in boxing. No fighting in front of customers; that was the rule. Put on a plastic smile faker than the plastic Kewpie dolls in hula skirts. Those were made in Taiwan. As if all islands in the Pacific are Hawaiian.

Two Japanese girls came in. Probably college students on winter break. The girls shuffled up and down the aisles, pawing over souvenirs.

I had better things to do than watch them. I needed to leave before I opened my mouth again about Tatan not helping. I couldn’t stand to see Nana all doe-eyed and hurt. Couldn’t stand when Tatan yelled at her like a five-year-old. Couldn’t stand it worse when I added my two cents and then everyone was mad at me.

Best I stock the shelves fast, then I could go body surfing with Tomas. Maybe Daphne would be there, and I could work up the nerve to ask her to go swimming with me. That’d take my mind off everything. Maybe even go reef-walking farther down-coast to catch octopus and sea cucumbers for dinner.

Hmm

, my stomach growled just thinking about it. If I had that knife, I wouldn’t have to wait for dinner. I could slice up the sea cucumbers and eat them raw.

Two cases to unload and I’d be on the beach. I was setting up thimbles and silver spoons with Guam’s US territorial seal on the end of the handles when one of the Japanese teens asked, “Where is Sammy?” She giggled. They always do, girls, they giggle behind their hands as if they just made a private joke.

“What?” Tatan said from behind the counter.

From where I was crouched I saw the girl in a sky blue bathing suit digging out money from her change purse to pay for a

sarong

. The other Japanese girl in a black one-piece suit and a straw hat pointed to the sign over the counter, SAMMY’S QUONSET HUT. Personally, I always thought KIKO’S QUONSET HUT had a nicer ring to it. Sammy wasn’t interested in running the store one day anyway.