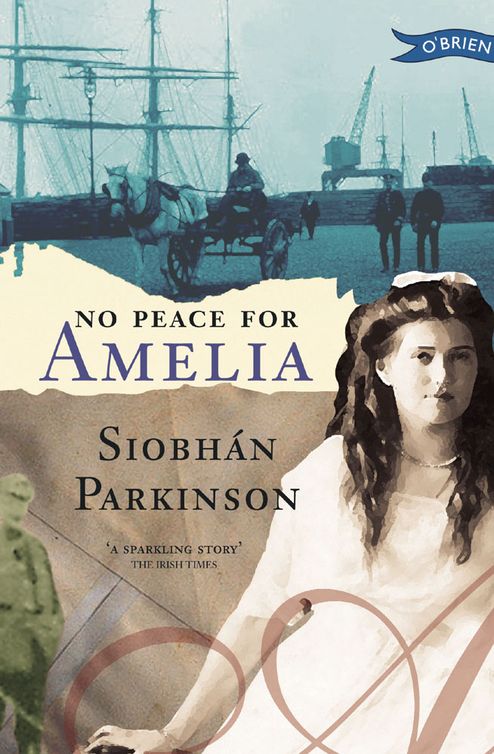

No Peace for Amelia

Read No Peace for Amelia Online

Authors: Siobhán Parkinson

A sequel to AMELIA

‘All young readers will enjoy this thrilling story of conflict, hope and courage’

EVENING HERALD

‘Recommended reading’

SUNDAY INDEPENDENT

OTHER BOOKS BY SIOBHÁN PARKINSON

Amelia

Four Kids, Three Cats, Two Cows, One Witch (maybe)

The Moon King

Breaking the Wishbone

Call of the Whales

The Love Bean

WINNER BISTO BOOK OF THE YEAR OVERALL AWARD

Sisters … No Way!

To Emily Pearson

Many thanks to Kevin Myers for his generous sharing of his deep and passionate knowledge of Ireland’s largely forgotten contribution to World War I.

Thanks also to Richard S. Harrison, who introduced me to Quaker ideas many years ago, and whose book

Irish Anti-War Movements 1874–1924

was a valuable reference document.

I used the following books as sources for facts about and

surrounding

the 1916 Rising:

Revolutionary Woman

(Kathleen Clarke; Dublin 1991: O’Brien Press),

Markievicz, The Rebel Countess

(Mary Moriarty and Catherine Sweeney; Dublin 1991: O’Brien Press). The illustrations of wartime recruitment posters in

Ireland and the First World War

(Dublin 1982: Trinity History Workshop) were a source of inspiration, and two are mentioned in the book.

Finally, I owe a debt of gratitude to Siobhán Pearson for checking the manuscript for accuracy, and to all the Pearson family, who were a

willing

resource on which she could draw for Quakerly guidance.

The characters in this book are entirely fictitious, despite their genuine Dublin Quaker surnames. Public events and historical figures

mentioned

in passing are, of course, real, and as accurate as I have been able to make them.

ONTENTS

This novel is set in Dublin in the spring of 1916. World War I (1914–18), which was mainly between Britain and Germany, was almost two years old, and many thousands of Irishmen had already joined up and been killed. These men joined Irish regiments of the British army, for of course there was no Irish army at the time, as Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom.

Before the war started, the government had promised Home Rule to Ireland. This meant that although Ireland would still remain within the United Kingdom, it would have much more independence and would have its own parliament and would be able to pass its own laws about things that had to do with

everyday

life in Ireland, while the government in London would still pass the laws that had to do with Ireland in relation to the outside world. Another thing the government had promised was votes for women.

Some Irish people didn’t think Home Rule was enough. These people were nationalists and they wanted complete

independence

from Britain. Other people, who were unionists, mainly Protestants in the northern part of the country, didn’t want Home Rule at all. They wanted to stay as part of the United Kingdom and to have no parliament in Dublin. But most people were happy enough with the idea of Home Rule.

Then the war came, and Home Rule was put aside for the moment. Some of the people who were in favour of Home Rule began to think they would never get it, and some nationalists, who thought Home Rule was not enough in any case, were quite sure that Home Rule wasn’t ever going to happen, because they saw how powerful the unionists were in the London parliament. These people decided that the only way to get independence was to fight for it, and so they started to prepare for armed rebellion.

There were various private armies in Ireland at the time. The

unionists had the Ulster Volunteers, who were prepared to fight to make sure that Ireland stayed part of the United Kingdom, and the nationalists had the Irish Volunteers, who were prepared to fight to make sure that Ireland did break away from the United Kingdom. The Citizen Army was another, smaller army,

consisting

mainly of trade unionists, which was preparing for an industrial insurrection. The Citizen Army, led by James Connolly and Countess Constance Markievicz, joined up with the Irish

Volunteers

, and together they planned a Rising for Easter Sunday, 1916.

Eoin (John) MacNeill, who was the commander of the Irish Volunteers, was not too keen on the idea of an armed

insurrection

at that time, but he did in the end agree to the Rising when he heard that the Germans were sending arms to help the Irish. The Germans sent the arms, but they were caught as they came to harbour, and MacNeill decided that the Rising would fail and should be cancelled.

So he put a notice in the paper for Easter Sunday, cancelling the Rising. The other leaders of the Rising decided to go ahead anyway, without MacNeill, and so they did. They held the Rising on Easter Monday, one day late. The Volunteers, led by Patrick Pearse, Thomas Clarke and others, took over the General Post Office in the centre of Dublin and proclaimed the Irish Republic from the front of this building, and flew the Irish tricolour flag.

On the same day that the Rising was happening in Dublin, hundreds of other Irishmen were gassed in northern France, in the war.

The Rising lasted only a week, and in the end the Volunteers surrendered, mainly because they knew they couldn’t win against the mighty British army, and they wanted to prevent more violence and bloodshed. The people mostly thought they were mad, and Dubliners jeered at the Volunteers as they were arrested and marched off through the streets to be deported to prison camps in England for their rebellion.

But shortly after the Rising, the leaders were executed by the British – sixteen of them in the space of a few weeks. The

executions

made the people feel sorry for the rebels, and more people started to support them than had supported them at the time of the Rising.

After the war, Irish women were granted the vote, long before women in Britain. Within a few years of the end of World War I, Ireland had another armed rebellion, known as the War of

Independence

, followed by a civil war. Eventually, Ireland – or at least most of it – won its independence from Britain and is now a republic. A small part of the country, in the northeast, remained part of the United Kingdom. It is known as Northern Ireland.