New York at War (16 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

By that evening, British and Hessian regiments under Charles Lord Cornwallis had taken the village of Flatbush, where Dutch farm families welcomed them with open arms and the Dutch Reformed pastor invited them to raid the wine collection of David Clarkson, one of the few local “rebels.” Over the next three days, Pennsylvania riflemen sent out from the American lines skirmished inconclusively with the enemy around Flatbush.

Washington remained wary. Convinced that the Long Island assault might well be a feint to divert him from an impending main attack on northern Manhattan, he redeployed some regiments from Manhattan to Kings County but continued to spend most of his time at his command center in a townhouse at No. 1 Broadway, in the shadow of Fort George. On August 25 he replaced his Long Island field commander, General John Sullivan, with his own second-in-command, Israel Putnam. All three generals were convinced that defending Gowanus Heights and three of the roads that passed through its center was the key to holding Long Island and preventing Howe from approaching Manhattan from the east. If held back here, the redcoats would never threaten the interior line of fortifications that stood precariously close to the city itself. “At all hazards prevent the enemy’s passing the wood and approaching your works,” Washington ordered.

19

But Sullivan, Putnam, and Washington had committed a fatal blunder, one that exposed their near-total inexperience as battlefield commanders. They had posted troops on three roads—the Martense Lane Pass, the Flatbush Pass, and the Bedford Pass—that ran through Gowanus Heights toward the villages of Brooklyn, Bedford, and the inner defensive line. But somehow they had neglected to position more than a light patrol on a fourth road, the Jamaica Pass, “a deep winding cut” that also ran through Gowanus Heights, further to the east.

20

One officer did perceive how the Jamaica Pass utterly jeopardized the American hold on Gowanus Heights and the inner line behind it. Unfortunately for the Continental army, that officer was General Sir Henry Clinton, Lord Howe’s second in command. Moody and petulant, Clinton quarreled often with Howe and other staff officers over campaign strategy. As the son of a former royal governor of New York Colony, Clinton had spent part of his youth in the city, and he felt that his superior knowledge of the city’s terrain and surroundings entitled him to direct the New York campaign. Clinton argued doggedly for a main assault against northern Manhattan to cut the rebels off from the mainland—the assault Washington feared—but he failed to convince the cautious Howe, who preferred an offensive through Kings County to secure Brooklyn Heights and the commanding artillery positions that could sweep the city.

Now, with the Long Island campaign in motion, Clinton was the first to see an opportunity for a brilliant victory—one that might even end the war in a single sharp blow. Clinton grasped that the unguarded Jamaica Pass exposed Washington’s army to a classic textbook maneuver. If Howe’s troops could get through the pass undetected and then move west behind the backs of the Americans on Gowanus Heights, they would flank the Continental regiments there, cut them off from their inner line of defenses, and subject them to a total rout. Taking the wooden stockades at Fort Putnam and Fort Greene would then be a mere mopping-up operation, leaving the door wide open for an assault on the vulnerable Fort Stirling. Clinton lobbied hard for his plan, this time finally managing to sway the skeptical Howe. The assault was set for the night of August 26. Sir Henry himself would have the honor of leading an advance guard of four thousand through the Jamaica Pass.

21

By 9 that evening, under a full moon, Clinton’s force, followed by corps commanded by Howe, Hugh Earl Percy, and Cornwallis, started moving up the King’s Highway from the hamlet of Flatlands toward the Jamaica Pass. Fourteen thousand men were on the march; their column, complete with baggage wagons and horse-drawn field pieces, stretched along the road for two miles. Behind them they left campfires burning to deceive the distant Americans. Tory scouts from the nearby village of New Utrecht guided the army off the road through adjoining fields so as to minimize the risk of being discovered by American pickets or patrols.

Moving slowly and quietly, with frequent stops so paths could be cleared through underbrush using saws rather than noisy axes, the column reached Jamaica Pass by 3 AM, when the redcoats easily surprised and captured the only American force posted to defend the crucial passage—five mounted officers. The cold night march exhausted and irritated its participants, who could hardly believe that the Americans would not discover the maneuver and ambush them. Captain James Murray of the King’s Fifty-seventh Regiment of Foot complained of “halting every minute just long enough to drop asleep and to be disturbed again in order to proceed twenty yards in the same manner.” But as the sun rose at 5:30, the army, having covered eight miles, reached its destination: the village of Bedford, directly in the rear of the still-oblivious front line of Continental regiments spread along the crest of Gowanus Heights.

22

By then, as the sound of distant cannon and musket fire told the tired British regiments, the battle had already begun. Howe and Clinton had decided on a three-pronged assault. As Clinton’s main assault force flanked Gowanus Heights, five thousand troops under Major General James Grant would divert the Americans by attacking the right (western) end of their forward line near the Martense Lane Pass, while General Philip von Heister would launch a similar feint by leading Hessian and Highlands regiments in a frontal assault on the American center ranged along the Heights. The gunfire must have initially puzzled Howe and Clinton, for the three attacks were supposed to commence simultaneously, in response to signal cannons to be fired at 9 AM. But Grant’s troops had literally jumped the gun. During the night, hungry scouts from one of his regiments had been spotted by American pickets as they hoisted watermelons from a field next to the Red Lion Tavern, just west of the Martense Pass. By dawn, Grant’s men had been exchanging fire with Pennsylvanians in the woods on the American right flank for several hours.

23

In the townhouse at the foot of Broadway, George Washington awoke that morning to the “deep thunder of distant cannon” drifting over the East River from Long Island. Continuing British troop movements from Staten Island to Long Island had finally convinced him that Howe’s invasion of Kings County was the main event. He had already begun to redeploy regiments from Manhattan to Brooklyn, and now, on the morning of the twenty-seventh, he ordered over more troops as he prepared to cross the river himself. One of the soldiers making the passage was a sixteen-year-old Connecticut private named Joseph Plumb Martin, who later recalled stuffing his knapsack with hardtack from casks standing by the Maiden Lane Ferry, just north of Wall Street, as he boarded a small boat bound for the Brooklyn shore. “As each boat started, three cheers were given by those on board, which was returned by the numerous spectators who thronged the wharves,” Martin remembered. Unbeknownst to Washington or Martin, the reinforcements from Manhattan were stepping into the trap Clinton and Howe were ready to spring on them.

24

At 9 AM on August 27, with the firing of the British signal guns, the Battle of Brooklyn (also known as the Battle of Long Island) began in earnest. As Grant’s troops intensified their musket and cannon fire against the right flank of the American forward line, and as von Heister’s Hessians and Scotsmen marched with fixed bayonets on the American center, Clinton’s grenadiers and light infantry surged west and south from Bedford, firing into the American rear along the Heights. As musket balls shattered tree branches and cracked into stone walls, clusters of British and American soldiers intermingled in a murderous free-for-all. William Dancey, a British infantry captain, found himself and his men running across a field, “exposed to the fire of 300 men. . . . I stopped twice to look behind me and saw the riflemen so thick and not one of them of my own men. I made for the wall as hard as I could drive, and they peppering at me. . . . At last I gained the wall and threw myself headlong.”

25

The Continental line on Gowanus Heights soon collapsed, as Clinton’s redcoats drove most of the fleeing Americans before them back toward the inner line of fortifications or toward the right flank of the American front line, where Grant was still pressing forward. On the south slope of Gowanus Heights, a similar rout was taking place, as von Heister’s men rounded up bloodied and surrendering rebels. The plain remained a killing field after the Americans laid down their arms, for some of the Germans and Highlanders vented their fatigue, rage, fear, and contempt by butchering prisoners. “It was a fine sight to see,” bragged one English officer, “with what alacrity they dispatched the rebels with their bayonets after we had surrounded them so they could not resist.” Another British officer was appalled to witness “the massacres made by the Hessians and Highlanders after victory was decided.”

26

As panicking Americans ran west toward their own right flank, Washington and his field commanders sought desperately to regroup the army and make a stand there. With Cornwallis’s corps hammering down from the northeast, von Heister pouring through the Flatbush Pass from the southeast, and Grant pressing from the southwest, Lord Stirling rallied several regiments in the marshy fields near a farmhouse and a millpond that ran into Gowanus Creek. Recalling that Grant had boasted in Parliament that he could easily march from one end of the American continent to the other with five thousand British regulars, Stirling tried to calm his shaken troops. “We are not so many,” he declared, “but I think we are enough to prevent his advancing farther over the continent than this millpond.”

27

But the onslaught of enemy musket fire and cannon volleys was relentless; the noose around the American front line grew ever tighter. New Yorker fought New Yorker, as the British threw Tory militia against local Continental units. Stirling came to see that the stand was hopeless and resolved on a holding action that would, he hoped, permit the bulk of the army to escape back to the inner line of defense. Leading four hundred of his best-trained troops, the Fifth Maryland Regiment (the “Dandy Fifth,” for its elegant scarlet and buff uniforms and the tidewater aristocrats who peopled its ranks), Stirling charged Cornwallis’s front six times, each time enduring a withering fire of canister and grapeshot “like a shower of hail.” One American participant remembered how the British cannon fire wreaked havoc, “now and then taking off a head.” Behind them, other Americans tried to make their escape, many of them plunging west and north across Gowanus Creek and the eighty yards of the marshy millpond. Arriving with his regiment too late to be thrown into the fray, Joseph Plumb Martin watched from the far bank: “such as could swim got across; those that could not swim, and could not procure any thing to buoy them up, sunk. . . . When [the survivors] came out of the water and mud to us, looking like water rats, it was truly a pitiful sight.” Watching the Marylanders’ last-ditch effort from a temporary command post on the rise called Cobble Hill behind the inner line of fortifications, Washington allegedly exclaimed, “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose!”

28

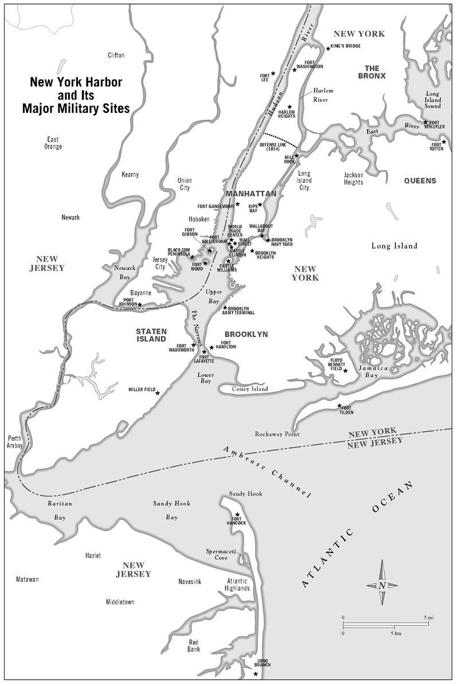

New York Harbor

and Its

Major Military Sites

All the survivors of the American forward line now retreated to the inner fortifications, running or limping into the trenches and stockades of forts Greene and Putnam and the line of redoubts connecting them. By early afternoon, it was over. “Long Island is made a field of blood,” a Manhattan minister wrote to his wife. Only gradually did the full horror of the disaster become clear to Washington and his battered army. The commander concluded that he had lost over a thousand men (modern estimates place American losses at about three hundred dead, several hundred more wounded or missing, and over one thousand taken prisoner). Howe reported total British and Hessian casualties as fewer than four hundred. Among Howe’s prisoners were generals Stirling and Sullivan; a third general, Nathaniel Woodhull, had been mortally wounded by his captors, allegedly after he refused their demand that he say, “God save the King.” And now Howe’s army stood poised at the gates of forts Putnam and Greene. In many instances the Americans had fought bravely, but they had been outgeneraled, outmaneuvered, and outfought. The Continental army’s first full-fledged field engagement was over. The question now was whether it could survive another one.

29

But General Howe hesitated, to the disbelief of the spent Americans and the consternation of his own officers. Rather than following up his triumph with a decisive blow, Howe ordered his sappers to begin digging trenches toward the American lines, a sign that he intended to besiege the enemy in his lair rather than breach his walls with a frontal assault. Howe’s caution remains puzzling more than two centuries later. Why not follow through with another charge and defeat Washington’s army once and for all? The answer, however, is not hard to find. Howe was by nature deliberate and careful, traits that served him poorly during the New York campaign. Just as inhibiting, perhaps, was his long-standing hope that he and his brother, Admiral Richard Lord Howe, could serve as peace commissioners, persuading the American leaders to see the wisdom of ending the rebellion and resuming their proper place in the empire. Even the brief respite that siege preparations required, following the drubbing the Americans had received on Gowanus Heights, might give Congress the time it needed to come round. But the general had miscalculated—gravely. Washington had blundered at the Jamaica Pass; now it was Howe’s turn.