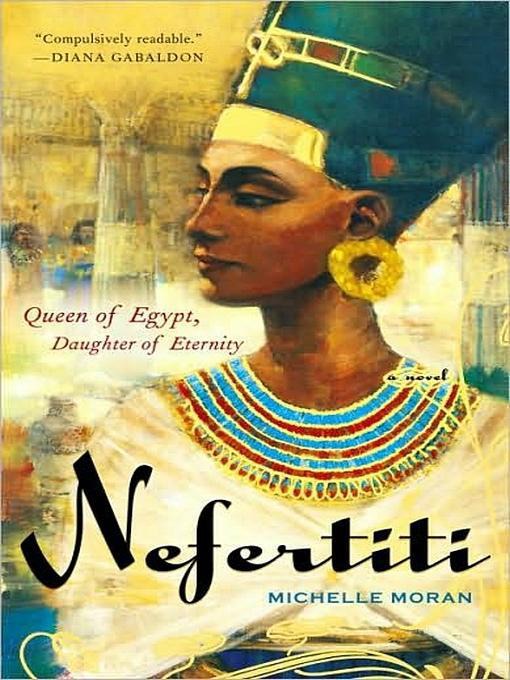

Nefertiti

Contents

To my father, Robert Francis Moran, who gave me his love of language and books. You left too soon and never saw this published, but I think, somehow, you always knew. Thank you for knowing, and for your magnificent life, which inspired me in so many ways

.

To speak the name of the dead is to make them live again.

—EGYPTIAN PROVERB

Author’s Note

IT HAS BEEN A long journey for me into Nefertiti’s ancient world, a journey that began with a visit to the Altes Museum in Berlin, where her iconic bust is housed. The bust itself has a long and detailed history, beginning with its creation in the city of Amarna and continuing to its arrival in Germany, where it became an instant draw in its first exhibition in 1923.

Even three thousand years after her death, Nefertiti’s allure still captivates tens of thousands of visitors each year. Encased in glass, it was her mysterious smile and powerful gaze that attracted me, making me wonder who she had been and how she’d become such a dominant figure in ancient Egypt.

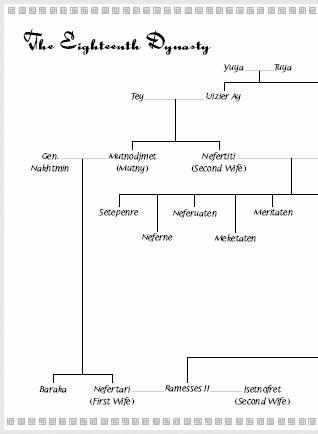

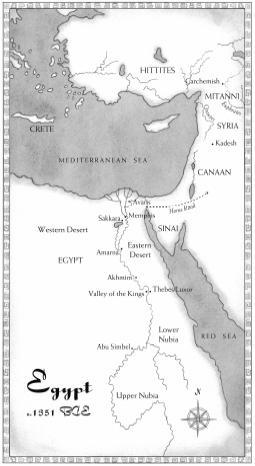

Now the time is 1351 BCE. The great Pharaohs of Egypt have included Khufu, Ahmose, and the female Pharaoh Hatshepsut, while Ramses and Cleopatra are yet to come. Nefertiti is fifteen years old. Her sister is thirteen, and all of Egypt lies before them.

Prologue

IF YOU ARE to believe what the viziers say, then Amunhotep killed his brother for the crown of Egypt.

In the third month of Akhet, Crown Prince Tuthmosis lay in his room in Malkata Palace. A warm wind stirred the curtains of his chamber, carrying with it the desert scents of zaatar and myrrh. With each breeze the long linens danced, wrapping themselves around the columns of the palace, brushing the sun-dappled tiles on the floor. But while the twenty-year-old Prince of Egypt should have been riding to victory at the head of Pharaoh’s charioteers, he was lying in his bedchamber, his right leg supported by cushions, swollen and crushed. The chariot that had failed him had immediately been burned, but the damage was done. His fever was high and his shoulders slumped. And while the jackal-headed god of death crept closer, Amunhotep sat across the room on a gilded chair, not even flinching when his older brother spat up the wine-colored phlegm that spelled possible death to the viziers.

When Amunhotep couldn’t stand any more of his brother’s sickness, he stalked from the chamber and stood on a balcony overlooking Thebes. He crossed his arms over his golden pectoral, watching the farmers with their emmer wheat, harvesting in the heavy heat of the day. Their silhouettes moved across the temples of Amun, his father’s greatest contributions to the land. He stood above the city, thinking of the message that had summoned him from Memphis to his brother’s side, and as the sun sank lower, he grew besieged by visions of what now might be.

Amunhotep the Great. Amunhotep the Builder. Amunhotep the Magnificent

. He could imagine it all, and it was only when a new moon had risen over the horizon that the sound of sandals slapping against tile made him turn.

“Your brother has called you back into his chamber.”

“Now?”

“Yes.” Queen Tiye turned her back on her son, and he followed her sharp footfalls into Tuthmosis’s chamber. Inside, the viziers of Egypt had gathered.

Amunhotep swept the room with a glance. These were old men loyal to his father, men who had always loved his older brother more than him. “You may leave,” he announced, and the viziers turned to the queen in shock.

“You may go,” she repeated. But when the old men were gone, she warned her son sharply, “You will

not

treat the wise men of Egypt like slaves.”

“They

are

slaves! Slaves to the priests of Amun who control more land and gold than we do. If Tuthmosis had lived to be crowned, he would have bowed to the priests like every Pharaoh that came—”

Queen Tiye’s slap reverberated across the chamber. “You

will not

speak that way while your brother is still alive!”

Amunhotep inhaled sharply and watched his mother move to Tuthmosis’s side.

The queen caressed the prince’s cheek with her hand. Her favorite son, the one who was courageous in battle as well as life. They were so much alike, even sharing the same auburn hair and light eyes. “Amunhotep is here to see you,” she whispered, the braids from her wig brushing his face. Tuthmosis struggled to sit and the queen moved to help him, but he waved her away.

“Leave us. We will talk alone.”

Tiye hesitated.

“It’s fine,” Tuthmosis promised.

The two princes of Egypt watched their mother go, and only Anubis, who weighs the heart of the dead against the feather of truth, knows for certain what happened after the queen left that chamber. But there are many viziers who believe that when judgment comes, Amunhotep’s heart will outweigh the feather. They think it has been made heavy with evil deeds, and that Ammit, the crocodile god, will devour it, condemning him to oblivion for eternity. Whatever the truth, that night the crown prince, Tuthmosis, died, and a new crown prince rose to take his place.

Chapter One

1351 BCE

Peret, Season of Growing

WHEN THE SUN set over Thebes, splaying its last rays over the limestone cliffs, we walked in a long procession across the sand. In a twisting line that threaded between the hills, the viziers of Upper and Lower Egypt came first, then the priests of Amun, followed by hundreds of mourners. The sand cooled rapidly in the shadows. I could feel the grains between the toes of my sandals, and when the wind blew under my thin linen robe, I shivered. I stepped out of line so I could see the sarcophagus, carried on a sledge by a team of oxen so the people of Egypt would know how wealthy and great our crown prince had been. Nefertiti would be jealous that she’d had to miss this.