My Swordhand Is Singing (2 page)

Read My Swordhand Is Singing Online

Authors: Marcus Sedgwick

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Horror & Ghost Stories

“Father?”

Tomas stopped for a moment and looked, not at his son, but somewhere away over his shoulder.

“He was found hanging from a tree by a rope round his neck. So he killed himself. Wouldn’t be the first lonely woodcutter to have done that.”

Something occurred to Peter.

“Why isn’t he going to be buried in his own village?”

His father grunted.

“That type of death. They wanted nothing to do with him. Said he died on Chust land so we could deal with him.”

“And we agreed?” asked Peter.

“Who is ‘we’? There is no ‘we’ here,” Tomas said abruptly. Then he sighed. “There was no choice. It was that, or leave him to the wolves. And anyway, the Elders commanded it.”

They were out of the village now, and through the trees they could see a few people gathered in a small clearing.

Peter thought about Radu, about how he might have died. His father told him he was a dreamer, but Peter couldn’t dream what might have happened to Radu. It was not the stuff of dreams, it was the stuff of nightmares.

“But Father,” Peter whispered, “you said Radu’s chest was burst, that his heart was pierced.”

“What of it?”

“Well, he can’t have done that to himself and then hung himself from a tree.”

“So it must have happened afterward.”

“You mean someone else did it to him after he was dead? Who would do that? Why?”

Tomas shrugged. “The wolves…?”

Peter was about to reply, but could tell his father was being deliberately obtuse.

“Listen, Peter. If a man is hanging from a tree by a rope, he killed himself. If Anna told them that’s what happened, then that’s what happened. Let it lie!”

Peter was not satisfied, but said no more. There was something troubling his father, he knew.

They made their way toward the meagre funeral party. There was Daniel, the priest; and Teodor, the feldsher—half doctor, half sorcerer. Radu might have been only a woodcutter, and not even from the village, but still two of its most important inhabitants had come to bury him. Peter wondered why. Why were both of them here? He knew they didn’t always get on. People were as likely to visit Teodor with spiritual needs as Daniel, and just as likely to pray for their health with Daniel as visit the doctor. Each man knew he had to tolerate the other. An uneasy alliance.

A little way away stood the village sexton, an old man with strong arms but few teeth. It was clear he wanted nothing to do with the affair, and having struggled to dig a shallow hole in the frozen ground, he leant on the top of his tall spade, sucking his gums, peering out from under a wide-brimmed black felt hat.

Snow continued to trickle down around and about as Tomas nodded greetings to the others.

Outsiders were never welcome, even though this father and son had taken to their work well enough. They were a strange pair. The father was a drunk, everyone knew that, but there was an air about him. Something in the way he held himself. He was fat from drink, his face flushed and his eyes milky, but he still had a head of strong black hair.

The son was a young man, really, new to the game. He had even darker, thicker hair, and his skin was smooth and brown, as if he was from somewhere in the south. His eyes were rich and dark brown, like Turkish coffee, but he was nervous, for all his young strength, and there was something about him that made him seem more refined than his father. Few of the villagers had ever wondered what might have happened to the boy’s mother, though it must have been from her that his refinement came.

Peter was absorbed in his own thoughts. Wolves couldn’t have done that to Radu’s chest after he hung himself from the tree. It didn’t make sense. Someone must have stabbed him through the heart with great force, and then hung his body in the tree afterward.

But why? Most murderers tried to conceal their victims’ bodies. Why display Radu’s body instead?

To Peter, it seemed like a warning, a warning that death was walking in the woods.

And Peter was right.

3

The Suicide’s Burial

Here came the body, uncovered on the back of Florin’s cart, pulled by an ox rather than a horse. Peter had seen this in other villages, the locals believing that the horse was too pompous an animal to be trusted at funerals, and was flighty too, inclined to kick and bridle, disturbing the dead person’s soul.

No one wanted that.

Besides, oxen were dependable, and noble in their own way.

Florin was a farmer, but there was little farming to be done in the winter and he had been told to fetch Radu’s body. This didn’t please him, but Anna had instructed him and he could not refuse. She was the most fearsome of the

kmetovi,

the village elders, a terrifying lady of unknown age who commanded total obedience. She had assumed control of the village after her husband died, and no one had dared to dispute this state of affairs. Her husband might have been a ruthless man, but even so he was just a shadow of Anna. So Florin had made his way to the woodshed behind the church, where Radu had been put, though Anna herself was having nothing to do with the burial.

There was something that did not impress the villagers favorably. Radu’s body had lain unguarded in the shed since he had been found. Anything could have happened to it. A cat might have jumped across it, and everyone knew what that could mean. But then Radu was already a suicide, so maybe there was no hope for him now anyway. His future was already in great danger.

Florin walked on one side of the head of his ox, and Magda, his old wife, walked on the other. Peter was surprised she had come, but not surprised to hear her singing. She sang the song that was always sung whenever anyone died, or was married, or, indeed, when anything important happened at all. Peter had heard it many times, in all the other places they had lived. It was called the Miorita. The Lamb.

“By a rolling hill at Heaven’s doorsill,

Where the trail descends to the plain and ends,

Here three shepherds keep their flocks of sheep.”

As Peter listened to the song, his mind began to drift. When he was a child he had been fascinated by the song’s story—the little lamb that talks to its faithful master, the murderous shepherds, the princess. The mother, who will wait in vain for her son to return. Peter had never known his mother, but though he tried very hard to feel something of a life that never happened to him, nothing came. Later, as he grew up, he thought about the story in more detail, and came to think it baffling and stupid.

Peter’s dreams were shaken from him by a snort from the ox.

Radu had arrived.

There was little ceremony. Peter’s father helped Florin lift the body from the cart, Daniel mumbled some words from the Bible, and the sexton glared from underneath his hat. Peter watched, disturbed by the brevity of it all. Was there really so little to celebrate in a life that would soon be forgotten forever? He gazed at Radu’s face. He had seen dead bodies before, everyone had, but the look that was literally frozen on Radu’s face shook him. It was a mix of shock and horror—and incomprehension. Peter shuddered, and wished that he and his father were back in their hut by the stove.

There was no coffin. The men lowered the body into the hole. But then something strange happened. Now in the grave, Radu was turned over, so that he lay face down. This wasn’t something Peter had seen before.

Florin had wheeled his ox around, and he and Magda began to trundle away, both riding in the cart. Peter turned to see Teodor step forward. Teodor untied a cloth bundle that he had been holding all the while, and a clutch of twigs fell into the snow. Just before the sexton started to pile clods of soil over Radu, Teodor placed the twigs on and around his body. They were short, but stout, thick with long sharp thorns. Peter knew they were hawthorn, and he glanced at his father for some explanation. But Tomas’s lips were tightly drawn.

The funeral was over, and each party went their own way back to the village.

In the square, Tomas clutched his son’s arm. It was only midway through the afternoon and already the light was failing. Peter’s mind was full of questions, about the funeral, about why they had attended it at all. He’d been astonished when his father said they would go, but maybe it was the right thing to do. It was just that it was a long time since Tomas had done the right thing.

Tomas shook his shoulder.

“I’m tired. Let’s go home, Son.”

Peter smiled.

“Lean on me, Father.”

Tomas draped his arm around his son.

“I think there’s some slivovitz left.”

The smile slipped from Peter’s face, but as they made their way, he dutifully supported his father’s weight.

“Why did they turn him face down?” Peter asked.

Tomas said nothing.

“What were the thorns for?”

“They’re not for anything,” Tomas snapped, pulling away from his son. “They’re simple, superstitious people here. Don’t take any notice of their foolishness.”

“But—”

“But nothing, Peter. We have wood to cut. And plum brandy to drink.”

And Peter knew, as so often, which of them would be cutting wood and which of them drinking brandy.

4

The Goose

Dusk fell with the snowflakes as father and son made their way home. Peter was as tall as his father now, and certainly as strong. Maybe Tomas had once been a powerful man, but Peter could not remember that time. Tomas did less and less work, and relied more and more on Peter to keep them fed. As far back as Peter could recall, Tomas had drunk. Once upon a time it must have been different. Peter’s mother had died giving birth to him. Tomas had found a wet nurse, but had brought Peter up himself ever since the child could walk and talk. Maybe he hadn’t been able to afford the nurse anymore, but it seemed he had wanted the woman out of their lives as soon as possible. Since then it had been just the two of them.

On Peter’s fifth birthday Tomas had given him a clasp knife. Not a toy, but a well-made and useful tool.

“Time you learnt to use one,” Tomas said.

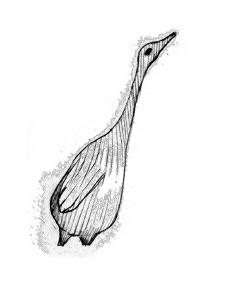

Peter had watched, entranced, as his father took an off-cut of a branch and quickly carved a small bird for him. A goose.

“It’s a good one,” Tomas said. “Sharp.”

“Yes, it’s a good one,” his little son had echoed, laughing, though it was not the knife he meant, but the slender little goose, the very image of the birds that he loved to gaze at as they flew overhead.

Later, Tomas taught him to read, and that wasn’t the action of a drunkard, nor even a soldier, but once Tomas had belonged to a very different kind of family. Now the drink seemed to possess him, and it cost Peter a lot of effort chopping logs to buy a bottle of slivovitz or rakia.

As they came within sight of the hut, Peter could see the birch smoke trailing up from the chimney, gently twisting into ghostly shapes in the dusk, drifting away and spreading like mist through the treetops.

Peter smiled. The fire was still alight; the hut would be warm.

The hut stood in a strange position. The river Chust, from which the village took its name, forked in two here, as it snaked through the woods. With deep banks, the river had spent ten thousand years eating its way gently down into the thick, soft, dark forest soil. Its verges were moss-laden blankets that dripped leaf mold into the slow brown water. But at a certain point in its ancient history, the river had met some solid rock hidden in the soil, and had split in two. It was at the head of this fork that the hut stood.