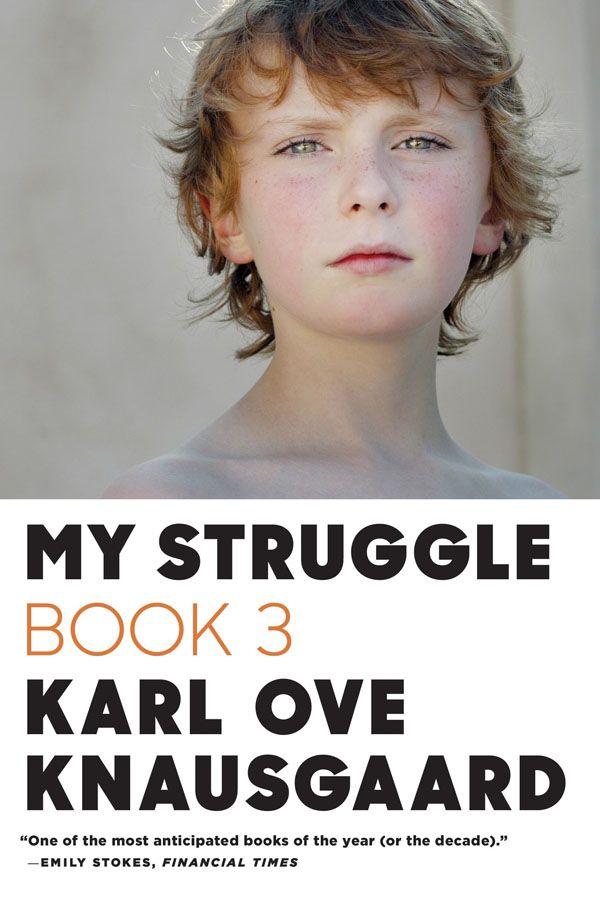

My Struggle: Book 3

My Struggle

Book Three: Boyhood

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

http://us.macmillan.com/content.aspx?publisher=macmillansite&id=25699

.

One mild, overcast day in August 1969, a bus came winding its way along a narrow road at the far end of an island in southern Norway, between gardens and rocks, meadows and woods, up and down dale, around sharp bends, sometimes with trees on both sides, as if through a tunnel, sometimes with the sea straight ahead. It belonged to the Arendal Steamship Company and was, like all its buses, painted in two-tone-light and dark-brown livery. It drove over a bridge, along a bay, signaled right, and drew to a halt. The door opened and out stepped a little family. The father, a tall, slim man in a white shirt and light polyester trousers, was carrying two suitcases. The mother, wearing a beige coat and with a light-blue kerchief covering her long hair, was clutching a stroller in one hand and holding the hand of a small boy in the other. The oily, gray exhaust fumes from the bus hung in the air for a moment as it receded into the distance.

“It’s quite a way to walk,” the father said.

“Can you manage, Yngve?” the mother said, looking down at the boy, who nodded.

“Course I can.”

He was four and a half years old and had fair, almost white hair and tanned skin after a long summer in the sun. His brother, barely eight months old, lay in the stroller staring up at the sky, oblivious to where they were or where they were going.

Slowly they began to walk uphill. It was a gravel road, covered with puddles of varying sizes after a downpour. There were fields on both sides. At the end of a flat stretch, perhaps some five hundred meters in length, there was a forest that sloped down to pebbled beaches; the trees weren’t tall, as though they had been flattened by the wind blowing off the sea.

On the right, there was a newly built house. Otherwise there were no buildings to be seen. The large springs on the stroller creaked. Soon the baby closed his eyes, lulled to sleep by the wonderful rocking motion. The father, who had short, dark hair and a thick, black beard, put down one suitcase to wipe the sweat from his brow.

“My God, it’s humid,” he said.

“Yes,” she replied. “But it might be cooler nearer the sea.”

“Let’s hope so,” he said, grabbing the suitcase again.

This altogether ordinary family, with young parents, as indeed almost all parents were in those days, and two children, as indeed almost every family had in those days, had moved from Oslo, where they had lived in Thereses gate close to Bislett Stadium for five years, to the island of Tromøya, where a new house was being built for them on an estate. While they were waiting for the house to be completed, they would rent an old property in Hove Holiday Center. In Oslo he had studied English and Norwegian during the day and worked as a nightwatchman, while she attended Ullevål Nursing College. Even though he hadn’t finished the course, he had applied – and had been accepted – for a middle-school teaching job at Roligheden Skole while she was to work at Kokkeplassen Psychiatric Clinic. They had met in Kristiansand when they were seventeen, she had become pregnant when they were nineteen, and they had married when they were twenty, on the Vestland smallholding where she had grown up. No one from his family went to the wedding, and even though he is smiling in all the photos there is an aura of loneliness around him, you can see he doesn’t quite belong among all her brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, male and female cousins.

Now they’re twenty-four and their real lives lie before them. Jobs of their own, a house of their own, children of their own. There are the two of them, and the future they are moving into is theirs, too.

Or is it?

They were born in the same year, 1944, and were part of the first postwar generation, which in many ways represented something new, not least by dint of their being the first people in this country to live in a society that was, to a major degree, planned. The 1950s were the time for the growth of systems – the school system, the health system, the social system, the transport system – and public departments and services, too, in a large-scale centralization that in the course of a surprisingly short period would transform the way lives were led. Her father, born at the beginning of the twentieth century, was raised on the farm where she grew up, in Sørbøvåg in the district of Ytre Sogn, and had no education. Her grandfather came from one of the outlying islands off the coast, as his father, and his before him, probably had. Her mother came from a farm in Jølster, a hundred kilometers away, she hadn’t had any education either, and her family there could be traced back to the sixteenth century. As regards his family, it was higher up the social scale, inasmuch as both his father and his uncles on his father’s side had received higher education. But they, too, lived in the same place as their parents, Kristiansand, that is. His mother, who was uneducated, came from Åsgårdstrand, her father was a ship’s pilot, and there were also police officers in her family. When she met her husband she moved with him to his hometown. That was the custom. The change that took place in the 1950s and 1960s was a revolution, only without the usual violence and irrationality of revolutions. Not only did children of fishermen and smallholders, factory workers and shop assistants start at university and train to become teachers and psychologists, historians and social workers, but many of them settled in places far from the areas where their families lived. That they did all this as a matter of course says something about the strength of the zeitgeist. Zeitgeist comes from the outside, but works on the inside. It affects everyone, but not everyone is affected in the same way. For the young 1960s mother, it would have been an absurd thought to marry a man from one of the neighboring farms and spend the rest of her life there. She wanted to get out! She wanted to have her

own

life. The same was true for her brothers and sisters, and that was how it was in families countrywide. But why did they want to do that? Where did this strong desire come from? Indeed, where did

these new ideas

come from? In her family there was no tradition of anything of this kind: the only person who had left the area was her uncle Magnus, and he had gone to America because of the poverty in Norway, and the life he had there was for many years hardly distinguishable from the life he’d had in Vestland. For the young 1960s father, things were different: in his family you were expected to have an education, though perhaps not to marry a Vestland farmer’s daughter and settle on an estate near a small Sørland town.

But there they were, walking on this hot, overcast day in August 1969, on their way to their new home, him lugging two heavy suitcases stuffed with 1960s clothes, her pushing a 1960s stroller with a baby dressed in 1960s baby togs, white with lace trim everywhere, and between them, tripping from side to side, happy and curious, excited and expectant, was their elder son, Yngve. Across the flat stretch they went, through the thin strip of forest, to the gate that was open and into the large holiday center. To the right there was a garage owned by someone called Vraaldsen; to the left large red chalets around an open gravel area and, beyond, pine forest.

A kilometer to the east stood Tromøya Church, built in 1150 of stone, but some parts were older and it was probably one of the oldest churches in the country. It stood on a small mound and had been used from time immemorial as a landmark by passing ships and charted on all nautical maps. On Mærdø, a little island in the archipelago off the coast, there was an old

skip-pergård,

a residence testifying to the locality’s golden age, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when trade with the rest of the world, particularly in timber, flourished. On school trips to the Aust-Agder Museum classes were shown old Dutch and Chinese artifacts going back to that time and even further. On Tromøya there were rare and exotic plants that had come with ships discharging their ballast water, and you learned at school that it was on Tromøya that potatoes were first grown in Norway. In Snorri’s Norwegian king sagas the island was mentioned several times; under the ground in the meadows and fields lay arrowheads from the Stone Age and you could find fossils among the round stones on the long, pebbled beaches.

However, as the incoming nuclear family slowly walked through the open countryside with all their bags and baggage it wasn’t the tenth or the thirteenth, the seventeenth or the nineteenth centuries that had left their marks on the surroundings. It was the Second World War. This region had been used by German forces; they had built the barracks and many of the houses. In the forest there were low-lying brick bunkers, completely intact, and on top of the slopes above the beaches several artillery emplacements. There was even an old German airfield in the vicinity.

The house where they were going to live during the coming year was a solitary construction in the middle of the forest. It was red with white window frames. From the sea, which could not be seen, though only a few hundred meters down the slope, came a regular crashing of waves. There was a smell of forest and salt water.

The father put down his suitcases, took out the key, and unlocked the door. Inside, there was a hall, a kitchen, a living room with a wood burner, a combined bath and washroom, and on the first floor, three bedrooms. The walls weren’t insulated; the kitchen was equipped with the minimum. No telephone, no dishwasher, no washing machine, no TV.

“Well, here we are,” the father said, carrying their suitcases into the bedroom while Yngve ran from window to window peering out and the mother stood the stroller with the sleeping baby on the doorstep.

Of course, I don’t remember any of this time. It is absolutely impossible to identify with the infant my parents photographed, indeed so impossible that it seems wrong to use the word “me” to describe what is lying on the changing table, for example, with unusually red skin, arms and legs spread, and a face distorted into a scream, the cause of which no one can remember, or on a sheepskin rug on the floor, wearing white pajamas, still red-faced, with large, dark eyes squinting slightly. Is this creature the same person as the one sitting here in Malmö writing? And will the forty-year-old creature who is sitting in Malmö writing this one overcast September day in a room filled with the drone of the traffic outside and the autumn wind howling through the old-fashioned ventilation system be the same as the gray, hunched geriatric who in forty years from now might be sitting dribbling and trembling in an old people’s home somewhere in the Swedish woods? Not to mention the corpse that at some point will be laid out on a bench in a morgue? Still known as Karl Ove. And isn’t it actually unbelievable that one simple name encompasses all of this? The fetus in the belly, the infant on the changing table, the forty-year-old in front of the computer, the old man in the chair, the corpse on the bench? Wouldn’t it be more natural to operate with several names since their identities and self-perceptions are so very different? Such that the fetus might be called Jens Ove, for example, and the infant Nils Ove, and the five- to ten-year-old Per Ove, the ten- to twelve-year-old Geir Ove, the twelve- to seventeen-year-old Kurt Ove, the seventeen- to twenty-three-year-old John Ove, the twenty-three- to thirty-two-year-old Tor Ove, the thirty-two- to forty-six-year-old Karl Ove – and so on and so forth? Then the first name would represent the distinctiveness of the age range, the middle name would represent continuity, and the last, family affiliation.

No, I don’t remember any of this, I don’t even know which house we lived in, even though Dad pointed it out to me once. All I know about that time I have been told by my parents or have gleaned from photos. That winter the snow was several meters high, the way it can be in Sørland, and the road to the house was like a narrow ravine. There Yngve is, pulling a cart with me in the back, there he is, with his short skis on, smiling at the photographer. Inside the house, he is pointing at me and laughing, or I am standing on my own holding on to the cot. I called him “Aua”; that was my first word. He was also the only person who understood what I said, according to what I have been told, and he translated it for Mom and Dad. I also know that Yngve went around ringing doorbells and asking if there were any children living there. Grandma always used to tell that story. “Are there any children living here?” she would say in a child’s voice and laugh. And I know I fell down the stairs, and suffered some kind of shock, I stopped breathing, went blue in the face, and had convulsions, Mom ran to the nearest house with a telephone, clutching me to her breast. She thought it was epilepsy, but it wasn’t, it was nothing. And I know that Dad thrived in the classroom, he was a good teacher, and that during one of these years he went on a trip into the mountains with his class. There are some photos from then, he looks young and happy in all of them, surrounded by teenagers dressed in the casual way that was characteristic of the early 1970s. Woolen sweaters, flared trousers, rubber boots. Their hair was big, not big and piled-up as in the sixties, but big and soft, and it hung over their soft teenage faces. Mom once said perhaps he had never been as happy as he was during those years. And then there are photos of Grandma on Dad’s side, Yngve, and me – two taken in front of a frozen lake, both Yngve and I were clad in large woolen jackets, knitted by Grandma, mine mustard yellow and brown – and two taken on the veranda of their house in Kristiansand, in one she has her cheek against mine, it is autumn, the sky is blue, the sun low, we are gazing across the town, I suppose I must have been two or three years old.

One might imagine that these photos represent some kind of memory, that they are reminiscences, except that the “me” reminiscences usually rely on is not there, and the question is then of course what meaning they actually have. I have seen countless photos from the same period of friends’ and girlfriends’ families, and they are virtually indistinguishable. The same colors, the same clothes, the same rooms, the same activities. But I don’t attach any significance to these photos, in a certain sense they are meaningless, and this aspect becomes even more marked when I see photos of previous generations, it is just a collection of people, dressed in exotic clothes, doing something that to me is unfathomable. It is the era that we take photos of, not the people in it, they can’t be captured. Not even the people in my immediate circle can. Who was the woman posing in front of the stove in the flat in Thereses gate, wearing a light-blue dress, one knee resting against the other, calves apart, in this typical 1960s posture? The one with the bob? The blue eyes and the gentle smile that was so gentle it barely even registered as a smile? The one holding the handle of the shiny coffee pot with the red lid? Yes, that was my mother, my very own mom, but who was she? What was she thinking? How did she see her life, the one she had lived so far and the one awaiting her? Only she knows, and the photo tells you nothing. An unknown woman in an unknown room, that is all. And the man who, ten years later, is sitting on a mountainside drinking coffee from the same red thermos top, as he forgot to pack any cups before leaving, who was he? The one with the well-groomed black beard and the thick black hair? The one with the sensitive lips and the amused eyes? Yes, of course, that was my father, my very own dad. But who he was to himself at this moment, or at any other, nobody knows. And so it is with all these photos, even the ones of me. They are voids; the only meaning that can be derived from them is that which time has added. Nonetheless, these photos are a part of me and my most intimate history, as others’ photos are part of theirs. Meaningful, meaningless, meaningful, meaningless, this is the wave that washes through our lives and creates its inherent tension. I draw on everything I remember from the first six years of my life, and all that exists in terms of photos and objects from that period, they constitute an important part of my identity, filling the otherwise empty and memoryless periphery of this “me” with meaning and continuity. From all these bits and pieces I have built myself a Karl Ove, an Yngve, a mom and dad, a house in Hove and a house in Tybakken, a grandmother and grandfather on my dad’s side, and a grandmother and grandfather on my mom’s side, a neighborhood and a multitude of kids.