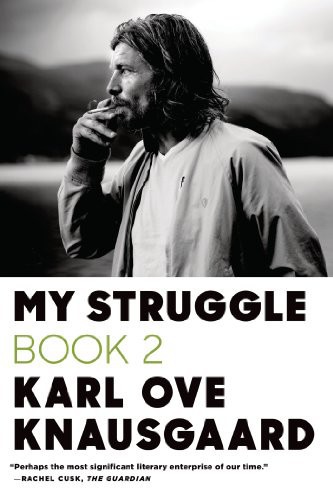

My Struggle: Book 2: A Man in Love

Read My Struggle: Book 2: A Man in Love Online

Authors: Karl Ove Knausgaard,Don Bartlett

Contents

About the Book

Karl Ove Knausgaard leaves his wife and everything he knows in Oslo for a fresh start in Stockholm. There he strikes up a deep and competitive friendship with Geir and pursues Linda, a beautiful poet who captivated him years ago.

A Man in Love

, the second book of six in the

My Struggle

cycle, sees Knausgaard write of tempestuous relationships, the trials of parenthood and an urge to create great art. His singular insight and exhilarating honesty must be read to be believed.

About the Author

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s first novel,

Out of the World

, was the first ever debut novel to win The Norwegian Critics’ Prize, and his second novel,

A Time to Every Purpose Under Heaven

, was widely acclaimed.

A Death in the Family

, the first of the

My Struggle

cycle of novels, was awarded the prestigious Brage Award. The

My Struggle

cycle has been heralded as a masterpiece wherever it appears.

Don Bartlett lives in Norfolk and works as a freelance translator of Scandinavian literature. He has translated, or co-translated, a wide variety of Danish and Norwegian novels by such writers as Per Petterson, Lars Saabye Christensen, Roy Jacobsen, Ingvar Ambjørnsen, Jo Nesbo and Ida Jessen.

Also by Karl Ove Knausgaard

A Time to Every Purpose Under Heaven

A Death in the Family: My Struggle Book 1

A Man In Love

My Struggle: Book 2

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Translated from the Norwegian by

Don Bartlett

29 July 2008

THE SUMMER HAS

been long, and it still isn’t over. I finished the first part of the novel on 26 June, and since then, for more than a month, the nursery school has been closed, and we have had Vanja and Heidi at home with all the extra work that involves. I have never understood the point of holidays, have never felt the need for them and have always just wanted to do more work. But if I must, I must. We had planned to spend the first week at the cabin Linda got us to buy last autumn, intended partly as a place to write, partly as a weekend retreat, but after three days we gave up and returned to town. Putting three infants and two adults on a small allotment, surrounded by people on all sides, with nothing else to do but weed the garden and mow the grass, is not necessarily a good idea, especially if the prevailing atmosphere is disharmonious even before you set out. We had several flaming rows there, presumably to the amusement of the neighbours, and the presence of hundreds of meticulously cultivated gardens populated by all these old semi-naked people made me feel claustrophobic and irritable. Children are quick to detect these moods and play on them, particularly Vanja, who reacts almost instantly to shifts in vocal pitch and intensity, and if they are obvious she starts to do what she knows we like least, eventually causing us to lose our tempers if she persists. Already brimming with frustration, it is practically impossible for us to defend ourselves, and then we have the full woes: screaming and shouting and misery. The following week we hired a car and drove up to Tjörn, outside Gothenburg, where Linda’s friend Mikaela, who is Vanja’s godmother, had invited us to stay in her partner’s summer house. We asked if she knew what it was like living with three children, and whether she was really sure she wanted us there, but she said she was sure; she had planned to do some baking with the children and take them swimming and go crabbing so that we could have some time to ourselves. We took her up on the offer. We drove to Tjörn, parked outside the summer house, on the fringes of the beautiful Sørland countryside, and in we piled with all the kids, plus bags and baggage. The intention had been to stay there all week, but three days later we packed all our stuff into the car and headed south again, to Mikaela and Erik’s obvious relief.

People who don’t have children seldom understand what it involves, no matter how mature and intelligent they might otherwise be, at least that was how it was with me before I had children myself. Mikaela and Erik are careerists: all the time I have known Mikaela she has had nothing but top jobs in the cultural sector, while Erik is the director of some multinational foundation based in Sweden. After Tjörn he had a meeting in Panama, before the two of them were due to leave for a holiday in Provence, that’s the way their life is: places I have only ever read about are their stamping grounds. So into that came our family, along with baby wipes and nappies, John crawling all over the place, Heidi and Vanja fighting and screaming, laughing and crying, children who never eat at the table, never do what they are told, at least not when we are visiting other people and really

want

them to behave, because they know what is going on. The more there is at stake for us, the more unruly they become, and even though the summer house was large and spacious it was not large or spacious enough for them to be overlooked. Erik pretended to be unconcerned, he wanted to appear generous and child-friendly, but this was continually contradicted by his body language, his arms pinned to his sides, the way he went round putting things back in their places and that faraway look in his eyes. He was close to the things and the place he had known all his life, but distant from those populating it just now, regarding them more or less in the same way one would regard moles or hedgehogs. I knew how he felt, and I liked him. But I had brought all this along with me, and a real meeting of minds was impossible. He had been educated at Oxford and Cambridge, and had worked for several years as a broker in the City, but on a walk he and Vanja took up a mountainside near the sea one day he let her climb on her own several metres ahead of him while he stood stock-still admiring the view, without taking into account that she was only four and incapable of assessing the risk, so with Heidi in my arms I had to jog up and take over. When we were sitting in a café half an hour later – me with stiff legs after the sudden sprint – and I asked him to give John bits of a bread roll I placed beside him, as I had to keep an eye on Heidi and Vanja while finding them something to eat, he nodded, said he would, but he didn’t put down the newspaper he was reading, did not even look up, and failed to notice that John, who was half a metre away from him, was becoming more and more agitated and at length screamed until his face went scarlet with frustration, since the bread he wanted was right in front of him but out of his reach. The situation infuriated Linda, sitting at the other end of the table – I could see it in her eyes – but she bit her tongue, made no comment, waited until we were outside and on our own, then she said we should go home. Now. Accustomed to her moods, I said she should keep her mouth shut and refrain from making decisions like that when she was in such a foul temper. That riled her even more of course, and that was how things stayed until we got into the car next morning to leave.

The blue cloudless sky and the patchwork, windswept yet wonderful countryside, together with the children’s happiness and the fact that we were in a car, and not a train compartment or on board a plane, which had been the usual mode of travel for the last few years, lightened the atmosphere, but it was not long before we were at it again because we had to eat, and the restaurant we found and stopped at turned out to belong to a yacht club, but, the waiter informed me, if we just crossed the bridge, walked into town, perhaps 500 metres, there was another restaurant, so twenty minutes later we found ourselves on a high, narrow and very busy bridge, grappling with two buggies, hungry, and with only an industrial area in sight. Linda was furious, her eyes were black, we were always getting into situations like this, she hissed, no one else did, we were useless, now we should be eating, the whole family, we could have been really enjoying ourselves, instead we were out here in a gale-force wind with cars whizzing by, suffocating from exhaust fumes on this bloody bridge. Had I ever seen any other families with three children outside in situations like this? The road we followed ended at a metal gate emblazoned with the logo of a security firm. To reach the town, which looked run-down and cheerless, we had to take a detour through the industrial zone for at least fifteen minutes. I would have left her because she was always moaning, she always wanted something else, never did anything to improve things, just moaned, moaned, moaned, could never face up to difficult situations, and if reality did not live up to her expectations, she blamed me in matters large and small. Well, under normal circumstances we would have gone our separate ways, but as always the practicalities brought us together again: we had one car and two buggies, so you just had to act as if what had been said had not been said after all, push the stained rickety buggies over the bridge and back to the posh yacht club, pack them into the car, strap in the children and drive to the nearest McDonald’s, which turned out to be at a petrol station outside Gothenburg city centre, where I sat on a bench eating a sausage while Vanja and Linda ate theirs in the car. John and Heidi were asleep. We scrapped the planned trip to Liseberg Amusement Park, it would only make things worse given the atmosphere between us now; instead, a few hours later, we stopped on impulse at a shoddy so-called ‘Fairytale Land’, where everything was of the poorest quality, and took the children first to a small ‘circus’ consisting of a dog jumping through hoops held at knee height, a stout manly-looking lady, probably from somewhere in eastern Europe, who, clad in a bikini, tossed the same hoops in the air and swung them around her hips, tricks which every single girl in my first school mastered, and a fair-haired man of my age with curly-toed shoes, a turban and several spare tyres rolling over his harem trousers, who filled his mouth with petrol and breathed fire four times in the direction of the low ceiling. John and Heidi were staring so hard their eyes were popping out. Vanja had her mind on the lottery stall we had passed, where you could win cuddly toys, and kept pinching me and asking when the performance would finish. Now and then I looked across at Linda. She was sitting with Heidi on her lap and had tears in her eyes. As we came out and started walking down towards the tiny fairground, each pushing a buggy, past a large swimming pool with a long slide, behind whose top towered an enormous troll, perhaps thirty metres high, I asked her why.

‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘But circuses have always moved me.’

‘Why?’

‘Well, it’s so sad, so small and so cheap. And at the same time so beautiful.’

‘Even this one?’

‘Yes. Didn’t you see Heidi and John? They were absolutely hypnotised.’

‘But not Vanja,’ I said with a smile. Linda returned the smile.

‘What?’ Vanja said, turning. ‘What did you say, dad?’

‘I just said that all you were thinking about at the circus was that cuddly toy you saw.’

Vanja smiled in the way she often did when we talked about something she had done. Happy, but also keen, ready for more.

‘What did I do?’ she asked.

‘You pinched my arm,’ I answered. ‘And said you wanted to go on the lottery.’

‘Why?’ she asked.

‘How should I know?’ I said. ‘I suppose you wanted that cuddly toy.’

‘Shall we do it now then?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘It’s down there.’

I pointed down the tarmac path to the fairground amusements we could make out through the trees.

‘Can Heidi have one as well?’ she asked.

‘If she wants,’ Linda said.

‘She does,’ Vanja said, bending down to Heidi, who was in the buggy. ‘Do you want one, Heidi?’

‘Yes,’ Heidi said.

We had to spend ninety kroner on tickets before each of them held a little cloth mouse in their hands. The sun burned down from the sky; the air beneath the trees was still, all sorts of shrill, plinging sounds from the amusements mixed with 80s disco music from the stalls around us. Vanja wanted candyfloss, so ten minutes later we were sitting at a table outside a kiosk with angry persistent wasps buzzing around us in the boiling-hot sun, which ensured that the sugar stuck to everything it came into contact with – the tabletop, the back of the buggy, arms and hands – to the children’s loud disgruntlement; this was not what they envisaged when they saw the container with the swirling sugar in the kiosk. My coffee tasted bitter and was almost undrinkable. A small dirty boy pedalled towards us on his tricycle, straight into Heidi’s buggy, then looked at us expectantly. He was dark-haired and dark-eyed, possibly Romanian or Albanian or perhaps Greek. After pushing his tricycle into the buggy a few more times, he positioned himself in such a way that we couldn’t get out and he stood there with eyes downcast.

‘Shall we go?’ I asked.

‘Heidi wanted a ride,’ Linda said. ‘Can’t we do that first?’