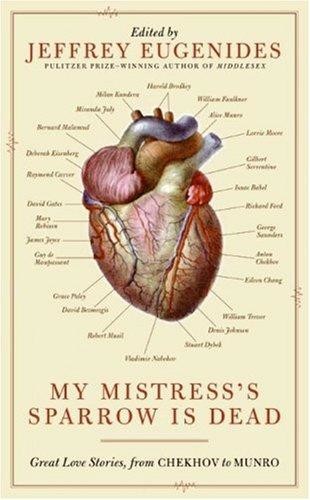

My Mistress's Sparrow Is Dead

Read My Mistress's Sparrow Is Dead Online

Authors: Jeffrey Eugenides

Tags: #Romance, #Anthologies, #Adult, #Contemporary

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Jeffrey Eugenides

FIRST LOVE AND OTHER SORROWS

Harold Brodkey

THE LADY WITH THE LITTLE DOG

Anton Chekhov

LOVE

Grace Paley

A ROSE FOR EMILY

William Faulkner

THE DEAD

James Joyce

DIRTY WEDDING

Denis Johnson

NATASHA

David Bezmozgis

SOME OTHER, BETTER OTTO

Deborah Eisenberg

THE HITCHHIKING GAME

Milan Kundera

LOVERS OF THEIR TIME

William Trevor

MOUCHE

Guy de Maupassant

THE MOON IN ITS FLIGHT

Gilbert Sorrentino

SPRING IN FIALTA

Vladimir Nabokov

HOW TO BE AN OTHER WOMAN

Lorrie Moore

YOURS

Mary Robison

THE BAD THING

David Gates

FIRST LOVE

Isaac Babel

TONKA

Robert Musil

JON

George Saunders

RED ROSE, WHITE ROSE

Eileen Chang

FIREWORKS

Richard Ford

WE DIDN’T

Stuart Dybek

SOMETHING THAT NEEDS NOTHING

Miranda July

THE MAGIC BARREL

Bernard Malamud

WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT LOVE

Raymond Carver

INNOCENCE

Harold Brodkey

THE BEAR CAME OVER THE MOUNTAIN

Alice Munro

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

Permissions

Other Books by Jeffrey Eugenides

Credits

Cover

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

JEFFREY EUGENIDES

1: LESBIA’S SPARROW

THE LATIN POET Catullus was the first poet in the ancient world to write about a personal love affair in an extended way. Other poets treated the subject of “love,” allowing the flushed cheeks or alabaster limbs of this or that inamorata to enter the frame of their poems, but it was Catullus who built his

nugae

, or trifles, around a single, near-obsessional passion for a woman whose entire presence, body and mind, fills the lines of his poetry. From the first excruciating moments of infatuation with the woman he called “Lesbia,” through the torrid transports of physical love, to the betrayals that leave him stricken, Catullus told it all, and, in so doing, did more than anyone to create the form we recognize today as the love story.

Gaius Catullus was born around 84 B.C., in Cisalpine Gaul, the son of a minor aristocrat and businessman with holdings in Spain and Asia Minor, and lived until roughly the age of thirty. It was as a very young man, then, that he found his way to poetry—and to Lesbia.

Lesbia wasn’t her real name. Her real name was Clodia. Classical scholars disagree over whether she was the Clodia married to the praetor Metellus Celer, infamous for her licentiousness and possible matricide.

Lesbia might have been one of Clodia’s sisters, or another Clodia altogether. What’s certain is that she was married and that Catullus’s relationship with her was adulterous. Though, like many adulterers, Catullus disapproved of adultery (in poem LXI he writes, “Your husband is not light, not tied/To some bad adulteress,/Nor pursuing shameful scandal/Will he wish to sleep apart/From your tender nipples,”), he found himself, in the case of Clodia/Lesbia, compelled to make an exception. He became involved with a wicked aristocratic Roman lady who used him as a plaything, or—the alternate version—he fell for a fashionable, married Roman girl, who ended up sleeping with his best friend, Rufus. Whatever the details, one thing is clear: a great love story had begun.

Of Catullus’s many hendecasyllabics devoted to his relationship with Lesbia, only two concern us here. The first two. The poems having to do with Lesbia and her pet sparrow.

Sparrow, my girl’s darling

Whom she plays with, whom she cuddles,

Whom she likes to tempt with finger-

Tip and teases to nip harder

When my own bright-eyed desire

Fancies some endearing fun

And a small solace for her pain,

I suppose, so heavy passion then rests:

Would I could play with you as she does

And lighten the spirit’s gloomy cares!

That’s poem II. Poem II A is a fragment. And by poem III Lesbia’s sparrow is dead. “[P]asser mortuus est meae puellae,/passer, deliciae meae puellae,/quem plus illa oculis suis amabit,” Catullus writes, which translates as, “My girl’s sparrow is dead,/Sparrow, my girl’s darling,/Whom she loved more than her eyes.” (Incidentally, this poem, or more specifically, the onomatopoeia of its two central words, “

passer

” and “

pipiabat

,” did more than anything I can remember to make me want to become a writer. I can still hear our Latin teacher, Miss Ferguson, piping out in her most piercing sparrow’s voice, “

passer pipiabat

,” getting us to notice how much the plosive rhythm resembled a bird singing. That words were music, that, at the same time they were marks on a page, they also referred to things in the world and, in skilled hands, took on properties of the things they denoted, was for me, at fifteen, an exciting discovery, all the more notable for the fact that this poetic effect had been devised by a young man dead for two thousand years, who’d sent this phrase drifting down the centuries to reach me in my Michigan classroom, filling my American ears with the sound of Roman birdsong.)

But back to the poem. The pluperfect of “

pipiabat

” is elegiac: the bird “used to sing.” Now its song has been silenced. Catullus, who in the previous poem had cause to wish the bird would fly away, now changes his mind. “Oh what a shame!” he writes. “O wretched sorrow! Your fault it is that now my girl’s/Eyelids are swollen from crying.”

Things were bad with the sparrow around. They’re bad with the sparrow gone. Nothing is keeping Lesbia from giving all her love to Catullus now. But Lesbia’s no longer in the mood. Worse, her crying has ruined her looks.

If Catullus gave us the confessional love story, these first two poems delineated its scope. The book you’re holding in your hands, which takes its title from Catullus, is an anthology of love stories. They were all written in the past 120 years. There are translations from Russian, Chinese, French, Austrian, and Czech writers. There are stories by famous, dead writers and by young Americans, stories involving, as in Milan Kundera’s “The Hitchhiking Game,” two lovers taking a road trip in Communist-era Czechoslovakia, to the two terrifically well-groomed, adolescent “TrendSetters & TasteMakers” from the near future in George Saunders’s “Jon,” to the little Jewish boy in Isaac Babel’s “First Love” who falls for the Christian neighbor who shelters him during a Russian pogrom. Despite the multiplicity of subjects and situations treated here, one Catullan requirement remains in force throughout. In each of these twenty-six love stories, either there is a sparrow or the sparrow is dead.

2: A LABOR OF LOVE

At the behest of the energetic, unstoppable Dave Eggers (the Bono of Lit), I’ve been reading almost nothing but love stories for the past year. (Note: The entire proceeds of this anthology will go to support 826 Chicago, the literacy project here in Bucktown, and another labor of love.) In discovering and gathering these stories, my method has been maximally random and sociable. At lectures and book parties, in elevators with editors and at literary festivals with fellow novelists, on college campuses, in loud tapas bars, over a Delirium Tremens at the Hopleaf on Clark Street, I asked whoever happened to be nearby to name a favorite love story. Jonathan Franzen, bobbing off the Amalfi Coast after an illegal dinner of sea urchins, suggested three separate stories by Alice Munro. Kathy Chetkovich nominated “Secretary” by Mary Gaitskill, which I didn’t select (not about love, I didn’t think) and Mary Robison’s “Yours,” which I did. Jhumpa Lahiri was the first of many to insist on “The Dead.” Asked to propose something from his own oeuvre, Martin Amis struggled to find anything sufficiently romantic. I didn’t confine myself to writers. Natasha Egan, of the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, mentioned a story I’d read a few years earlier and loved, David Bezmozgis’s “Natasha.” The German artist Thomas Demand had me look at Robert Musil’s difficult and rather punishing “Tonka,” which I tried my best to forget but couldn’t get out of my mind. (How like love!) Edwin Frank, editor of NYRB Books, was responsible for sending my way the work of the illustrious Chinese writer Eileen Chang, which was a revelation to me and, I suspect, will be a revelation to many American readers. And then there were the students and dinner party guests, the bookworm bartenders, the voluble taxi drivers.

Many stories in this collection didn’t need an advocate. They were among my favorite stories already. As a way to narrow literary focus, selecting “love” as your theme doesn’t help much. Viewed a certain way, almost any story appears to be a love story. Generally speaking, however, what animates most of the stories in this collection isn’t agape but eros. The love here is mainly romantic love. In almost every story you’ll find a lover and a beloved, a subject pursuing an object. In Miranda July’s “Something That Needs Nothing,” a young woman longs for the love of her best friend, only to finally win it at the expense of turning herself into another person. The spinster in William Faulkner’s southern gothic, “A Rose for Emily,” whose chances for marriage have been doomed by paternal opposition, devises a desperate measure, after her father’s death, to keep her next lover at her side. A frustrated teenage love affair leaves the narrator of Stuart Dybek’s “We Didn’t” with a memory more indelible than any resulting from consummation.

Other books

The Salt Road by Jane Johnson

Death Times Two (The V V Inn, Book 3.5) by Ellisson, C.J., Brux, Boone

The Candy Shop War, Vol. 2: Arcade Catastrophe by Brandon Mull

Celtic Stars (Celtic Steel Book 4) by Delaney Rhodes

Notes on a Near-Life Experience by Olivia Birdsall

The Big Burn by Jeanette Ingold

Hereafter by Tara Hudson

Shell Game (Stand Alone 2) by Badal, Joseph

River's End (River's End Series, #1) by Davis, Leanne

Russian Mafia Boss's Heir by Bella Rose