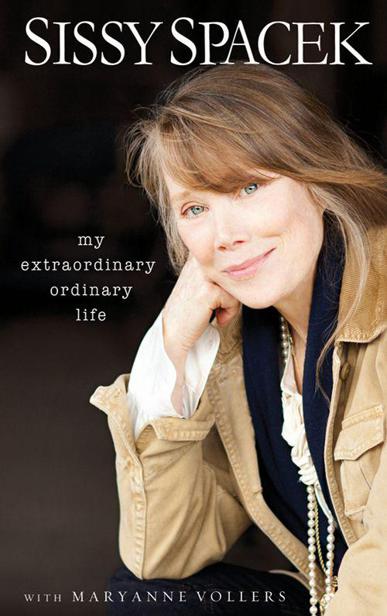

My Extraordinary Ordinary Life

Read My Extraordinary Ordinary Life Online

Authors: Sissy Spacek,Maryanne Vollers

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Rich & Famous, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Women

my extraordinary ordinary life

Sissy Spacek

with Maryanne Vollers

For my family

Magic Hour: “… when common things are touched with mystery and transfigured with beauty: when the warehouses become as palaces and the tall chimneys of the factory seem like campaniles in the silver air.”

—James Whistler, the painter, describing that time of day when the sun is low, and light transforms the mundane into the sublime

Contents

Little did I realize that what began in the alleys and backways of this quiet town would end up in the badlands of Montana.

—Holly Sargis,

Badlands

There’s nothing much to do in a small town on a warm summer morning. So I stand in the front yard, barefoot and in short shorts, twirling my baton. The trees cast long, familiar shadows over the carefully mowed lawns and clean-swept sidewalks. My arms and fingertips remember the routine all on their own, years of practice removing the effort from conscious thought, leaving only the sensation of dancing in the soft grass, knees pumping the air, spinning. I toss the baton and all I see is a sky so blue and clear it could swallow me whole. A dog barks somewhere in the distance; on another street a child is ringing his bicycle bell, but soon I hear nothing but the sound of my own breath, and the soft impact of the baton in my hand as it returns to earth. I am far away, lost in the rhythm of the spins and rolls, until I glimpse something moving on the street.

I spin again, then snap my eyes back to the ground; a pair of fancy black-and-white cowboy boots is walking toward me. The boots are attached to a pair of tight-fitting jeans, a dirty white T-shirt, a cute boy, much older than me, with hair like James Dean, watching. I drop the baton to my side, feeling suddenly exposed, uncomfortable in a new way.

“Hi, I’m Kit,” the boy says. “I’m not keeping you from anything important, am I?”

I meet his gaze.

“Cut!” says Terrence Malick, from behind the camera. Suddenly the spell is broken, and I’m back on location in La Junta, Colorado, with a small crew and a smattering of bystanders watching me and Martin Sheen play the opening scene of

Badlands

, a film that would soon change all of our lives.

Little did I know, when I was growing up in my own small town in Texas, that my skills as a twirler with the marching band would come in handy in my first starring role. Or that every experience, every story I heard as a child, every person who crossed my path, was like a gift that I would carry with me for the rest of my life.

Sometimes there’s no better entertainment than a town dump. When we were kids growing up in East Texas, my brothers and I would ride our bikes to the dump yard over behind the high school. To us it was a treasure trove of free and wonderful things, and we spent hours there sorting through the piles. At the entrance, people would drop off the better stuff, things that weren’t really trash, just used items that families had outgrown. That part was more flea market than landfill. Sometimes we would find old but perfectly good toasters, lengths of rope, used games, old toys, or boxes of paperback books. Animals were dropped off, too, in hopes that someone would give them a home.

One afternoon my brother Robbie rode home from the dump cradling a paper sack as if it was filled with diamonds. I watched as he dropped his bike in the grass and ran into the house, holding up the bag and yelling, “I found a kitten!”

My dad looked up from the newspaper.

“Can we keep it, Daddy?” he asked, still breathless.

I was just a few steps behind, chiming, “Can we, Daddy, please?”

“Yeah, we need a cat!” said Ed, our older brother.

She was a scraggly little calico, newly weaned, with six toes on each foot. After the three of us whined and pleaded for the rest of the day, our parents gave in. Our new pet had two names. Inside the house, where she was quiet and sort of mysterious, we called her Suzette. Outside, she was Cattywampus, a freewheeling mouse- and bird-hunter who roamed the neighborhood in search of adventure.

I’ve always thought of myself as a lot like that cat. My outside self was like Cattywampus: strong, sunny, competent, compassionate, funny, creative, and optimistic, heading out into the world wearing a smile and a bulletproof vest. My inside self was like Suzette: introspective, observant. The outside me was an open book; the inside me had secrets. Nothing earth-shattering—just the deepest thoughts I kept to myself, like the cigar box full of treasures that I had hidden under my bed. Anyone else who opened that box would have only seen a collection of ordinary objects: old cat’s-eye marbles, a tiny Coke bottle, a Jew’s harp, school photos of my little boyfriends with their awkward signatures scrawled across their faces. But to me each object held a special significance; they were my most precious things, talismans only I understood. I buried the cigar box in the backyard one day, hoping to preserve a time capsule of my life that I could revisit when I was older. I marked out the steps and drew a map of where I had dug the hole.

A few years later, I decided it was time to unearth the time capsule and remind myself of the past. I dug dozens of holes, but I couldn’t find it. Never did. Maybe my feet had grown, or the map was wrong. No matter. I still carry that box around with me in my head, while I collect new treasures along the way. I keep them safe in a part of me that no one ever sees; a storeroom where I sort and process the events of a long and interesting life. My mother’s lilting voice is there, speaking words of wisdom. So are my father’s strong, capable hands that could play a banjo or build a house; my brother’s trusting smile; the laughter of my children. This safe and quiet place—Suzette’s world—fuels my work as an actor and filmmaker. I know it’s always there within reach, inexhaustible as memory.

On Christmas Day, 1949, my mother got a silver soup ladle—and me. I had green eyes and red hair, and completely ruined the holiday for my brothers. Ed was six, and Robbie was only sixteen months old when I came along. The night before, my mother had been hanging decorations on the tree when she went into labor. She insisted that my father wait until she’d finished decorating and all the presents were wrapped before she let him take her to the nearest hospital, in Tyler, Texas. Daddy’s parents were visiting, and he borrowed their brand-new Chrysler for the thirty-eight-mile drive. They say he drove so fast, he burned the paint off that engine and made it just in time. I was born a few minutes after midnight. My parents named me Mary Elizabeth, but my brothers called me “Sissy,” and it stuck.

We lived in Quitman, a town of 1,237 souls nestled in the rolling farmland of East Texas, about ninety miles northeast of Dallas. My father, Edwin Spacek, was the Wood County agricultural agent. My mother, Virginia, known to all as Gin, worked for an abstract office in the courthouse when she wasn’t home with us. For seventeen years, Quitman was the center of my universe. I always appreciated the accident of my birth into such a wonderful world. As a child, I would lie in bed at night and think,

I’m so lucky to be born in Texas, to live in this house with these parents, and these brothers, and…

All the things that are most important to me, I had before I left that little town. My values were formed in a community where material possessions didn’t count for much, relationships were everything, and where waiting for something you wanted could actually be better than having it.

My brothers and I grew up together in a small ranch house that my father built on a half-acre lot along the Winnsboro Highway, a quarter mile from the center of town. The house had green clapboard siding and thick redwood trellises propping up the eaves on either side, which were perfect for climbing roses. Our dad, who came from a long line of Czech farmers, had a degree in agriculture, and he could make anything grow. Our yard was always a wonder, manicured and lush with flower beds and persimmon trees, pears and chestnuts. Daddy could never walk by a weed. Whenever one of us kids was home sick from school, he would leave work during his 10

A.M

. coffee break and stop by the drugstore to buy us a funny book. I would hear the sound of his car door slamming, and then wait for a long time before he got to the front door. I’d look out the picture window and see him in his suit and tie, pulling weeds from the lawn.

My father was a slim, handsome man with piercing almond-shaped eyes and high cheekbones. Like his father, who had owned a tailor shop, Daddy was an impeccable dresser—my favorite picture of him is as a young county agricultural agent, dressed in white linen pants, two-tone shoes, and a Panama hat, standing in a cotton field checking the crop. Our dad pretended to be strict with us. “Gin, you’re going to ruin those kids!” he’d say. “Just give me one week and I’ll straighten them out!” But even though he made us toe the line, he was really a soft touch. There was a time when my grandmother was sick and Mother had to leave us alone with him for a few weeks. He spoiled us rotten. One morning I woke up to see him standing over me with a dish towel draped over one arm and a breakfast tray in his hands.