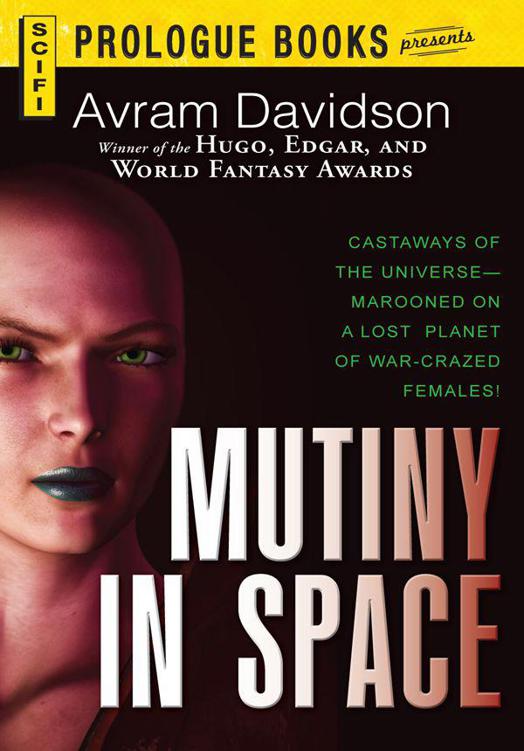

Mutiny in Space

Authors: Avram Davidson

Mutiny in Space

by Avram Davidson

a division of F+W Media, Inc.

a division of F+W Media, Inc.

I

T HAD NOT BEEN A BLOODLESS MUTINY BY ANY MEANS

. The Second Officer in particular had fought on with his fists long after everyone else had capitulated. He must have crippled a good few of them, and their friends had kicked him to death rather leisurely while the discussion about what to do with the surviving officers and loyal crewmen went on. He must have been in great pain; nothing else could have caused him to make quite so much noise; and it bothered Captain Marrus Rond that he couldn’t seem to remember the man’s name.

Of course, others had been killed too, but Rond hadn’t seen it happen, hadn’t even seen their bodies. So their deaths didn’t seem altogether real to him. But, then, neither did anything else.

Nothing was real, all was illusion — what did they used to say on Island L’vong on whatever that planet’s name was — the one in the P’vong Cluster? Oh, yes. “

I am being dreamed

….” And there was another saying, in one of the Archaic Romanic tongues of the pre-Technic Period,

“Life is a dream, and the dream is but a dream itself.”

That being the case, best to forget bad ones about familiar faces going bloody and making horrible sounds — best to forget.

Captain Rond desisted from conscious thought, slipped easily into uneasy sleep once more. He mouthed and moaned, but he did not know it.

“Only a fool points a gun when he doesn’t have to,” Larran Cane was saying. “And only a fool doesn’t point a gun when he has to.”

“Yes,” said Jory. “Yes, father.” He wondered why his father was pointing a gun at him now. But that was all wrong, he was telescoping things. His father had died the year Jory entered the Third Academy. It must have been the sight of Aysil Stone, with a gun in

his

hand, which had subconsciously reminded him. But why was Aysil Stone — ?

“On your lily-white, unsullied feet, former First Officer Jory Cane, and hop to it!”

The last words were almost screamed. White patches came and went on the man’s swollen face, his familiar red and swollen face, now suddenly so unfamiliar.

Jory hopped.

“ ‘I’m afraid the Leading Officer is drunk,’” Stone mimicked. “Why don’t you say it? You’ve said it often enough before on this voyage. So why not say it now?” His breath sounded, trembling, in his nose.

Jory had said it, often enough. That was true. Stone and he had made other voyages together — the Harrison-Hudson run, the Cluster tour, and the long, long haul to solitary Trismegistus — and Stone had often been drunk before, but never so often as on this voyage. When Jory was a new, green fourth mate, Aysil Stone was Mister First himself, right below the Leading Officer, who was right below the almighty captain himself, on that first voyage together on the HH run — way off in the blue-white suns of the Lace Pattern.

“A new brat,” he said at their first sighting, friendly enough. The new brat smiled. The cant phrase had reassured him that he was really a ship’s officer even more than the uniform had.

“I hope you keep that smile, brat,” said Aysil Stone. “I’ve been a first officer almost as long as you’ve been alive, and I quit smiling a long, long time ago. It’s the breaks, brat — either you get them or you don’t. I don’t. I

used

to get them. But not any more.” And Jory Cane had smelled the alcohol on his breath already then.

He could smell it now, not just the strong reek of the pale green distillate, but the harsh odor of ten thousand gallons of it, poured into the man’s mouth over the years — inhaled and ingested and digested and exhaled and transpired and flatulated and sternutated and voided — in short, every action of which the body mechanism was capable — until it was part of

him

and yet apart from him, like an aura, an atmosphere, a troposphere full of his other bad smells besides.

“Aysil, what the hell is this about?” he demanded now, keeping his hands flat at his sides.

Aysil Stone grinned his crooked grin, and for a moment Jory felt it was some minor — mad, but minor — caper. He relaxed. The gun, which had sagged a bit, now came up, sharp. The grin vanished.

“It’s the breaks, former First Officer Cane. I never got them, not till old Jarvy dropped dead and went out the garbage chute one week from port. So the Man made

me

L.O. Seniority forever — hurrah, boys, hurrah! Only, it’s for this voyage only. I’ll never make another, not as L.O. or as any other O. Too much greensleeve, brat, as who knows better. I’ll be cashiered — hey? On the beach — hey? At my age and with my service record — hey? No thank you. I never got the breaks, so now I’ll make the breaks.”

He flicked his finger at the light-stud of the wall communicator. Until that moment Jory hadn’t even realized that Stone must have flicked it silent when he came in. The sound panel seemed to explode as if in furious resentment at having been muted. Whoops, howls, laughs, screams, songs, shots — it was this last which convinced Jory that none of the noise was electronic.

“ — hear this, now hear this, now hear this, now you

listening

, all you apes and officers? You

listening — ?

”

Roars, whistles, hoots, shrieks.

“Second Officer Toms Tarkington just tried to swallow a mouthful of bloody teeth but seems like — hey hey! — he must of just bust a gut or something! Seems like they didn’t agree with him because he couldn’t keep ‘em down!”

And over and above all the noise (thuds, blows, and a horrible kind of howl that Jory had never heard before, a sound which his mind gave an almost physical wrench of refusal to even try to identify) another voice was heard suddenly, harsh and hoarse but quite devoid of any of the hysteria of the preceding one. It said: “Ays, where in the hell are you? Get your drunken butt up here topside, right now.”

Click

and the communicator was cut off at Central.

Once more Aysil Stone’s crooked grin. “What’s that old line from the Old Books?” he asked. “ ‘Better to rule in Hell than serve in Heaven’? Let’s go, brat.” He gestured with his gun toward the cabin door. “Let’s go.”

Now why was Larran Cane turning his face away? Was he angry? It was very odd, all very odd. Jory felt that he wanted to pull the covers over his head and go back to sleep — just go back to sleep.

• • •

A little creature very much like a lizard sat on a twig surveying something new and vast which he saw without seeing. Presently a pouch of skin at his throat inflated and bulged out. The little creature began to sing and warble like a bird.

• • •

Lockharn felt the cramp in his foot again. The only help for it was to get up and stand on it. Pressure would straighten it out right away. Get up and stand on it — only he was too tired. He wasn’t a young man anymore. But after this trip, boy, he would pension out and he’d buy that farm, and he’d let them all laugh at him. He wouldn’t care about that, only his foot …

Lockharn had been lying in his rack, looking at catalogues. They were his favorite form of reading material. They were, in fact, almost his only form of reading material.

Retirement Ranch in the hills of Ishtar, Southern Sector. 1,000 sq. km. in woodlands and mixed crops. Main cottage, 20 rms, latest fixtures. Rivers. Lakes. Wild life. Game preserve. Price 800,000. Nice little place for right party

. Lots of space-apes settled on Ishtar when they pensioned out — those who’d kept up their pensions, that is. Lots didn’t. And 800,000 … he’d saved just about three-and-a-half times that. Say another 800,000 to get the place fixed up right, because no matter what they might say, it always took at least as much as the price of a farm to fix it up. A few hundred thousand to live on until the income started coming in, and the rest — well, the rest for emergencies. Always keep something banked for emergencies.

Then the emergency came; and the bank didn’t help a bit.

The communicator said, “Now hear this, now hear this. Starship

Persephone

is no longer the property of the Guild of the Third Academy. It is no longer under the command of former Captain Marras Alton Rond. Starship

Persephone

is now the property of her crew — you and me, guys — and the command will be exercised for the moment by a junta consisting of Leading Officer Aysil Stone, Bosun Blaise Darnley, and Crewmen G. Race, S. Rase, and S. T. Clennor. An advisory committee to assist the junta will be elected as soon as we get things straightened out.

“This is a Free Ship now, and everybody better know what that means. Anybody don’t, be glad to explain. Any officers still at large, come in with your hands flat on top of your heads. Things are still peaceful, so let’s keep it like that. And you space-apes who haven’t signed the Declaration, don’t hang around picking your toes, for — sake, come on out and

sign

it!”

Slowly, slowly, very slowly, Lockharn started getting up from his rack. It was the obscenity which told him that it was not a joke. The clamor starting in the corridor would have warned him, soon enough, that something was very wrong. Then too, nobody joked about Free Ships over the communicator of a straight ship. Or joshed officers that way. But — most of all — it was the single, short obscenity. A word which Lockharn heard a thousand times each day and never had thought twice about until now, when he realized — and a sick realization it was, too — he had heard it over the communicator for the first time. It said more to him than a thousand words or a thousand clamors.

It said beyond possibility of mistake that Captain Marrus Alton Rond

was no longer

in command of Starship

Persephone

.

Men ran down the corridors shouting insanely, clapping each other on the back, punching and embracing each other. Two stewards and a storekeeper were doing a sedate little dance in the middle of it all, bowing and gesturing to each other. They broke off when they saw him emerge, and burst into broad grins.

“Locky! A Free Ship!”

“Hey, Pops, we’re gunna take the

Persy

to the P’vong Cluster, and sell her to the Forty Thieves; hey, Pops?”

“Locky! Locky! We’ll all be

millionaires!

”

He replied, stiffly, “It’s mutiny.”

They laughed. They stopped. Then the storekeeper said, “It’s the farm. He’s worrying about the farm.” And they all burst out laughing again. Carefully, their arms around him, they explained that he’d be able to buy all the farms he wanted — a dozen, a hundred, five hundred farms — with his share of the fabulous price the ship would bring on the Cluster’s famous and fabulous free market. He could even have his savings transferred, they assured him, although it would only be a drop in the bucket compared to his cut of the ship-price. There were twenty habitable planets in the Cluster, each one crazier and wider and better than the other; he could buy a farm on each one and have his own private and personal gig to visit between them.

“Because the beauty of it, Locky, the

beauty

of it — not only do they

rec

ognize the Free Ship principle there — ”

“

‘Recognize’

it? Hell, boy, they

invented

it!”

“ — but, no extradition, Locky! No extradition!”

“It’s a dream, it’s a dream, it’s a dream.”

Lockharn shook his head. “It’s mutiny,” he said.

And so, after awhile, they took his hands and put them flat on his head, and they marched him along and out and up to Central. They did stop, once, and tried to make him sign the Declaration, but he wouldn’t. And the other rioters, the other mutineers — how funny the word sounded! — spat at him, some of them. Others called him scab and fink and scissorbill and sham-ape — called him things he didn’t want ever to remember again — and made him watch what they did to Second Officer Tarkington. But he wouldn’t remember that, he wouldn’t; he had felt the pain of every boot and blow.