Murder on the Blackboard (6 page)

Read Murder on the Blackboard Online

Authors: Stuart Palmer

“They couldn’t find anything unless it had a thirty-foot neon sign over it,” Miss Withers told him sharply. “It’s a wonder those nitwits even found the furnace. Where are they now?”

“We’re about through for tonight,” the Sergeant confessed. “Allen and Burns searched the second floor classrooms, and now they’re going through these on the ground floor.”

“I hope they managed to find the second floor without difficulty,” Miss Withers remarked. “Did they find anything else of moment?”

The Sergeant drew himself up to his full five foot six. “They certainly did find something,” he retorted. “And it may have a deep bearing on this case. There was a full bottle of veronal in the desk of 2E!”

“Well, what of it? Why shouldn’t Alice Rennel quiet her nerves with veronal if she wants to? I’m sure if I had her fifth graders day in and day out, I’d need it, too.”

“Yeah,” said the Sergeant. “But veronal is a pretty strong sleeping powder. Why, you can’t even buy it in this state without a prescription from a doctor, and they give ’em out damn seldom.” He took a large round bottle from his pocket. “This was bought over in Jersey, according to the label.”

Miss Withers studied it. “What is more to the point, it’s still a full bottle. As far as I can see, you couldn’t cram another tablet in here with a crowbar. Besides, you don’t think that Anise Halloran was killed with poison, do you?”

“I’m not thinking, yet,” the Sergeant announced.

“Let me know when you start,” Miss Withers said softly. “Any time you’re ready, this case could use it.” Suddenly she changed her tone. “Any sign of the weapon?”

He shook his head. “Not unless the murderer used that shovel for hitting his victims and digging the grave, both. We’re having the thing taken to the analyst for bloodstains. No fingerprints on it, worse luck. Hey, Mulholland!” He turned and shouted down the hall.

“Bring that shovel here a minute!”

A sandy-haired man in a new and well-filled blue uniform marched down the hall from the rear. Over one wide shoulder, military fashion, was the tool in question.

“That’s a gardener’s spade, not a shovel,” Miss Withers informed the Sergeant. She looked at it, gingerly. There were no obvious signs of blood on its rusty blade. But all the same she drew away.

“Take it along,” she said. “There’s something worse about it than there would be about a bloody knife or a smoking pistol. A nice peaceful garden tool put to such a purpose …”

“I know what you mean, ma’am,” put in Mulholland. “My sisters’s cousin tamed wild horses on a ranch out west for years. Then he came back east and got run over by a brewery team on the street. He wasn’t bad hurt, but faith, it like to broke his heart …”

“That’ll do, Mulholland,” said the Sergeant.

Miss Withers tidied her back hair. “I think I’m going home,” she announced.

“I wish I was,” the Sergeant told her. “I don’t know whether I’m officially in charge of this case or not, but I’m going right ahead as if I was, in the place of the Inspector. We’re all through here for tonight. I’ll station a man in the hall outside the Cloakroom where the murder took place, and another at the main door. As soon as Allen and Burns get through with combing the ground floor I’ll take ’em with me and we’ll start the third degree.”

“Oh, yes? You’re going to question somebody?” Miss Withers stopped dead.

“We sure are. I’ll find out where this wren lived, and who her boy friends were, and we’ll soon be on the trail. Maybe she’ll have a roommate, and a good sock in the nose or two ought to make anybody talk.”

The Sergeant was strictly of the old school of detective investigation. Miss Withers was suddenly very thoughtful.

Her thoughts were interrupted by the raucous voices of the two precinct detectives, who burst out of the door of room 1A, across the hall, and approached excitedly.

“What d’you think, Sergeant, we found the dead dame’s office! This is it, right here.”

Miss Withers raised her eyebrows. “What makes you think that this was Miss Halloran’s room? I tell you, you’re mistaken.”

“Mistaken my eye,” said Burns doggedly. “She was the music teacher here, wasn’t she? Well, right in this room there’s a lot of music written on the blackboard. You can’t kid me—I used to be a choir boy.”

“The classroom you have just left belongs to Miss Vera Cohen, of the second grade,” Miss Withers told him.

“Well, what’s the notes doing there then?”

“Listen to me a moment, and I’ll enlighten you,” Miss Withers began. “Miss Halloran had a little office on the third floor, but most of her music work was given in the respective classrooms. Let me see—yes, tomorrow morning would be her morning with the second graders. She was just being beforehand tonight, and putting her scales and charts and things on the board so as to have everything in readiness for the morrow.”

“Let’s have a look at that room,” Sergeant Taylor decided. Miss Withers was already ahead of him.

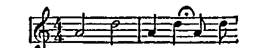

Everything seemed to be strictly in order within the domain of Miss Vera Cohen. Miss Withers’ keen eyes fell at once upon the marking which graced the blackboard in the front of the room.

It was here, then, that poor Anise Halloran had remained, after most of the other teachers had gone for the day, to prepare her work for tomorrow. It was here that she had drawn her last breaths of the murky, chalk-filled air of Jefferson School—and it was from this barren room that she had gone out into the hall to click on her high heels past Miss Withers’ door and down to the Teachers’ Cloakroom—with the shadow already upon her face, and the beating of vast invisible wings in her ears.

Had the girl a premonition of what awaited her there when she made these notations on the blackboard? Miss Withers wondered, for there was something wavery and irregular about the spacing of the lines, and something erratic about the notes, which was not like the neat work of Anise Halloran in the past.

Particularly was this true of the last line of music on the board, beneath the scales and the rendition of the hackneyed rondel, “Are you sleeping—are you sleeping, brother John?” The phases in question seemed to have been added in a hurry, as if Anise Halloran had been in haste to keep her appointment with Death.

This little tune, which ran off unfinished at the end, looked simple enough even for Miss Cohen’s second graders. But all the same, Miss Withers copied it into her notebook.

“Why are you bothering with that?” the Sergeant wanted to know. “I suppose you’re going to whistle up the murderer, the way sailors are supposed to whistle up a wind when they want one?”

“Maybe I am,” Miss Withers said. She was beginning to have her doubts about the Sergeant. This was his first taste of authority, and it was going to his head.

Well, it would do no harm to tell him this. “You want to know the reason I copied down this last bit of music? I’ll tell you, though you won’t take it seriously. It was the last thing Anise Halloran wrote. I like the feeling of something she used, something she touched, something that occupied her mind near the end. Not that I believe in second sight or anything like that—but you never can tell. There are fakirs in India, and even in this country, who can look at a ring, and tell you the personality of the person who wore it last.”

“It’s over my head,” Sergeant Taylor insisted. “I’m a practical man, I am. Well, we’ve done everything here that can be done. Just a minute while I make sure my men are stationed for the night, and we’ll clear out of here.” He went out into the hall.

“Mulholland!” A man stepped clear of the far doorway.

“Yes, sir?”

“Okay. Just wanted to make sure you were there. Where’s Tolliver?”

“Here, sir.”

Another bluecoat put in an appearance, a brawny bulk of beef with feet like scows.

“Mulholland, you’re stationed in the hall here, outside the Cloakroom. You and Tolliver will do guard duty tonight. Nobody goes in or out, you know enough to know that. You’ll be relieved in the morning some time. That is all.”

He swung on Miss Withers, authority resting upon his shoulders like a mantle. This was the Sergeant’s big hour.

“Say,” he queried, “do you happen to know where I can dig up the address of this girl who was bumped off? Have they got a record or something around the place?”

Miss Withers assured him that they had. “Wait here a moment,” she said, authoritatively.

Quickly she disappeared into the Principal’s office. Before the Sergeant could make up his mind to follow her, she had drawn out the file box from Janey Davis’ desk again.

Snatching a pen and dipping it in a nearby inkwell, she drew a tiny streamer at the top of the figure “1” in Anise Halloran’s street number. Now the card read “apartment 3C, 447 West 74th Street.”

“That ought to give me half an hour’s head start,” she figured rapidly. She came out into the hall and handed the card to the Sergeant.

Her mind was busy in an effort to discover some means of keeping this little Hawkshaw from tagging along. “By the way, Sergeant,” she suggested, “are you sure that you’ve found all there is to be found in the basement? I have a very strong hunch that the murder weapon is still down there—and that your shovel doesn’t mean a thing. Hadn’t you better look again?”

Sergeant Taylor drew himself up to his full height. “Say, listen,” he told the school-mistress. “Maybe we did slip up at first on the body and a few things like that. But don’t kid yourself. One thing my boys know how to do, and that’s to search a place. They’ve been over every inch of the floor downstairs with a filter and a fine-tooth comb, and unless the murder weapon was small enough for one of your red ants to carry down his ant-hole, I’ll stake my life on it that it ain’t there. No, ma’am, there ain’t nothing nor nobody down in that basement now. Unless”—he ventured a heavy jest,—“unless the ghost of the dead little dame is wailing around the furnace!” He laughed, heartily.

It was a laugh in which Miss Withers did not join. Neither did the joke seem to amuse Mulholland, he whose job tonight was to keep him on a lonely vigil here.

“Say, you don’t believe—” he started to say.

But his question, and the Sergeant’s hearty chuckles, were both clipped off as with a pair of shears.

From somewhere, out of the darkness and the loneliness of that ancient building, there came the sound of a human voice, raised in song. It was far away, and muffled, and there was a throaty, eerie note in it.

“There’s somebody upstairs!” shouted Detective Allen.

“No, it’s out on the playground …” Mulholland pointed wildly.

“You’re both wrong,” Miss Withers cut in. “Listen a moment.”

The voice came louder. It was no ghost, that was certain. It was the voice of a man, a gay man, a man who had nothing heavier than a feather upon his conscience or his mind.

The song was of the simplest. “Oh, I know an old soldier an’ he got a wooden leg, an’ he hadn’t no tobaccy and none could he beg….” These were the words, or at least as many of the words as the singer wished to sing. Slowly he came closer.

“I’ll get him,” the Sergeant promised.

“Wait,” Miss Withers put in. “He’s coming this way.” She looked at the Sergeant. “Are you sure that was a

fine-tooth

comb you combed the cellar with?”

The voice was very near now, rough and bawdy and boisterous. It was, of a certainty, coming up the basement stair … up from the basement that had been fine-combed so thoroughly and so often by the Sergeant and his men!

“Oh, there was an old soldier …”

The voice stopped, and an apparition in gray stared at the little group from the doorway at the end of the hall.

He was a man of medium size, with a thick head of colorless hair and a face that was seamed and wrinkled as a potato left too long in a damp, dark place. He wore a decent blue serge coat above denim overalls, and there was straw in his eyebrows and blood in his eye.

He swayed gently back and forth, like a wheat field in the breeze.

“Anderson!” gasped Hildegarde Withers breathlessly. “Anderson the janitor!”

Slowly Anderson came forward, putting each foot down carefully in front of the other, with his body as intense and rigid as if he were walking a tightrope.

He made a valiant and not too successful effort to stare them all in the face as he came to an abrupt halt against the wall.

“Whass comin’ off here?” he questioned. “Mgoing close upaplace.”

The Sergeant’s mouth widened a little. He looked toward Mulholland. “Take him.”

The big cop seized Anderson’s arm, and the janitor immediately slumped, head down. “Gong home,” he muttered. “Gong turnou’ lights….”

With a smile of satisfaction, the Sergeant pressed forward. He shook the man roughly by the shoulder. “Say, what do you know about this killing, huh? Come clean!”

Anderson blinked. “Abou’ wha’?”

“Answer me, or I’ll break your back! Where you been hiding out? Come on, or we’ll help your memory with a night-stick.”

“You can’t do this to me,” Anderson retorted, brightening a little. “’M a rich man. ’M a millionaire, if had m’rights.” Tears suddenly burst from his bleary eyes. “I been cheated, I tell you. Cheated! Thirteen’s m’lucky number, I tol’ her so. I tol’ her….”