Murder and Mayhem (15 page)

Authors: D P Lyle

Boneset

(Eupatorium perfoliatum),

also known as feverwort, ague-weed, or sweatplant, is a flowering plant that was dried and used to make a bitter tea. It causes flushing and sweating, and was used to treat fevers and also as a laxative. Several North American Indian

tribes found it useful, and it was adopted from them by European settlers. I know of no evidence that it was effective against malaria. Its use as a folk remedy, both then and now, is due to its ability to cause sweating, which was seen as beneficial. It is not.

What Exotic Diseases Are Prevalent in the Caribbean?

Q: My heroine's daughter returns from a trip to the Caribbean very ill, requiring that she be hospitalized. I thought of severe "turista" and hepatitis as possible illnesses but would prefer something a little more exotic. Any thoughts?

A: Schistosomiasis. Exotic enough?

A mouthful for sure, it is pronounced: shish-toe-so-my-a-sis. It is an infection caused by a trematode (a worm in the fluke family) and there are several species worldwide. In the Caribbean the most likely type would be

Schistosoma mansoni (S. mansoni).

It is endemic to many parts of the Caribbean, and victims contract it if they swim or bathe in water infected with the parasite. Any freshwater pond or stream can contain

S. mansoni.

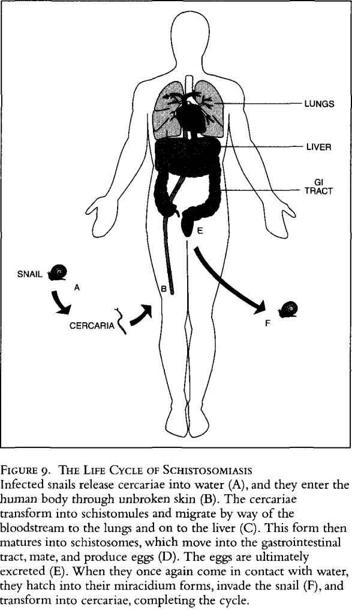

The life cycle of this parasite is complex and interesting (Figure 9). It requires the cooperation of two hosts (human and snail) and the metamorphosis of the organism into several distinct forms. The infective form is called a cercaria. It is a microscopic wormlike organism with a forked tail. It enters the body through unbroken skin that comes in contact with infected water. After entry it transforms into a form called a schistomule and migrates via the bloodstream to the lungs and then to the portal vein of the liver, where it matures into an adult schistosome. Males and females then pair up and migrate to the intestinal lining, where they set up housekeeping, mate, and begin to produce eggs. The eggs either remain in the intestinal tissues or are swept back to the liver. Either way,

they are ultimately excreted, and when they contact water again, they hatch into a miracidium, a free-swimming form that moves by way of cilia (external hairlike structures that function as paddles). These forms seek out and invade a specific species of snail. Within the snail they develop into cercariae, and are released into the water, and the cycle repeats itself

Within the human body the invasion, migration, and maturation period lasts about four to five weeks. During this time the victim typically has no symptoms, with the possible exception of mild itching for a day or so after initial exposure. Symptoms begin with the egg-laying stage. The most common symptoms are fever, chills, headache, hives or angioedema (puffy swelling of the hands, feet, and face, especially the lips and eyes), cough, weight loss, fatigue, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Occasionally the diarrhea may be bloody.

Diagnosis is difficult, mostly because schistosomiasis isn't considered. It is often confused with typhoid fever, amoebic dysentery, and other diarrheal or prolonged febrile diseases. Lab tests would show an increase in the white blood cell (WBC) count, particularly an elevation of eosinophils (a type of white blood cell) to greater than 50 percent of all WBCs (a normal level would be 3 to 5 percent). Diagnosis is established by finding the eggs in a stool specimen, from a biopsy of rectal tissues, or by a positive immunofluorescent antibody test.

Once diagnosed, treatment is fairly straightforward: a single dose of Oxamniquine (15 milligrams [mg] per kilogram [kg] of body weight [1 kg equals 2.2 pounds]) and three doses of Praziquantel, (20 mg per kg) given six hours apart. Let's say your character weighs about 120 pounds, or 55 kilograms. She would be given 825 mg of Oxamniquine at one time and three 1200-mg doses of Praziquantel six hours apart.

In your story the young victim could have gone swimming in a pool, perhaps near a romantic waterfall or in a tree-shaded stream. She would return home full of stories and feel completely normal. Six weeks later she could develop the "flu." Fever, chills, cough, and mild diarrhea would suggest such a diagnosis. Her M.D. would treat her with aspirin, fluids, and chicken soup, but she would become worse. More fever and chills, weight loss, and bloody diarrhea could develop. She would be hospitalized and evaluated for hepatitis, amoebic dysentery, and perhaps typhoid. Blood tests, bar

ium enemas, and cultures of her blood would reveal nothing except an elevation of the WBC and eosinophil counts. Liver and kidney studies would be normal. Finally, a stool specimen, sent to the lab to look for amoeba organisms, would show the schistosome eggs, and an immunofluorescent antibody test would be performed on a blood sample. The cute young doctor on whom she has developed a crush would make the diagnosis, treatment would be given, and she would go on with her life, none the worse for wear.

What Are the Symptoms and Signs of Spinal Muscular Atrophy?

Q: I've afflicted a major character in my book with chronic spinal muscular atrophy. The book is set in fifteenth-century Brittany and France. I chose this disease because I wanted one that would waste the character away, not be contagious, and be quite rare, so that no one would know what to do about it.

At the time my heroine meets him, he is in his twenties and his legs have already atrophied. He knows he is going to die as his brother did, but because the progress of the disease has temporarily slowed, he has hope that he has more years to live.

My critique group keeps asking for more symptoms of his suffering, though I do say his strength is going as the wasting and paralysis moves up his body, and he is in pain as it happens.

Does this scenario ring true? What else can you tell me about this rare disease?

A: Yes, your scenario works well, and you have obviously done your research.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) comes in at least three varieties:

1

. SMA I, Infantile SMA or Werdnig-Hoffmann disease,

is apparent at birth and has a rapidly fatal course. The infant has weak, floppy limbs and poor reflexes, and usually dies in the first year. Not suitable for your story.

2.

SMA II, Chronic Childhood SMA,

begins in later childhood and has a slowly progressive course.

3.

SMA III, Juvenile SMA or Wohlfart-Kugelberg-Welander disease,

begins during late childhood and has a slowly progressive course. This is probably best for your scenario.

These are all what we call "lower motor neuron diseases." They affect the neurons (nerve cells) of the lower spinal cord rather than those of the brain. Motor neurons are those involved in movement as opposed to sensation (sensory neurons). Other diseases in this family include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease). Stephen Hawking, the brilliant theoretical physicist, is afflicted with ALS.

SMA is an inherited disease, so the fact that your character's brother died from the same disease fits perfectly and adds a note of fear since the character knows what to expect. Of course, in the 1400s absolutely nothing was known about this disease, and it obviously wouldn't have a name. It is very likely that he would be considered a sinner or possessed or otherwise dangerous. At that time religion had a much stronger hold on people's beliefs than did science.

As you noted, the loss of motor nerve stimulation in your character leads to progressive atrophy of the muscles. This is usually more prominent in the larger proximal muscles of the shoulder and hip girdles. The thighs, upper arms, and shoulders become progressively weak and wasted, month by month and year by year.

Pain is not typical with these syndromes since they involve the motor neurons rather than the sensory ones.

The symptoms are simply a progressive loss of strength and muscle size, beginning in the larger muscles and progressing to the smaller ones. As the weakness advances, loss of coordination and the finer movements of the hands, for example, deteriorate. Handwriting, drawing, and playing with small objects would suffer. Handling eating utensils or other tools would become awkward and clumsy. Walking would become wider of gait (for better balance) and more shuffling in quality. Trips and falls would be common. The ability to stand, walk, and rise from a chair would become increasingly difficult. Eventually the victim would become chair- or bed-bound and more and more dependent on the help of others for feeding, bathing, dressing, and so forth. Through all this his mind would be completely intact, since this disease does not affect the brain. Of course, depression, sullenness, anger, and thoughts of suicide could appear.

What Type of Bacterial Meningitis Is Most Likely to Infect Adolescents?

Q: I have an unusual question. I am writing a fictional story that is loosely autobiographical. At age twelve, while attending a summer camp, I became very ill, was hospitalized for a couple of weeks, and nearly died. I remember little of the experience but later was told I had had bacterial meningitis and that many of the other kids at camp had the same thing. I want to use this event in my story and would appreciate your thoughts on what this might have been.

A: Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, which are the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. The most common at age eleven would be viral meningitis (caused by several different types of viruses) or bacterial meningitis (caused by either

Haemophilus influenzae

or

Neisseria meningitidis,

both of which are bacteria). The most likely culprit in the scenario you describe would be meningococcal meningitis, which is caused by

N. meningitidis.

Meningococcal meningitis most commonly occurs in children under three years of age or in adolescents between fourteen and twenty. It can become epidemic in closed communities such as camps, military bases, and schools, particularly where people come from varied parts of the country. Let me explain why this is so.

Many different strains or types of

N. meningitidis

exist. We all carry these and other bacteria in our nasopharynx (nose and throat). We are immune to them, as are most people in our immediate geographic area. After all, we live with them on a daily basis. When we go to another area of the country, we are exposed to people who carry different strains of the same bacteria. We may have no immunity against these strains because we have not been exposed to them on a regular basis and thus have not developed antibodies against them. Alternatively, someone may come into our area from another part of the country and expose us to their particular strain. Either way, we are at risk of developing an infection from this foreign bacterium.

This is particularly true for viruses. How many times have you or someone you know developed a flu or cold after a vacation or trip? When you travel in an airplane and visit other areas of the country or world, you are exposed to viruses that are not part of your normal environment. Since your immunity to these viruses is minimal or absent, you become ill.

N. meningitidis

is a common bacterium in our nasopharynx. When people from diverse areas gather, as in a camp or military base, someone may bring in a particularly virulent strain to which many of the group, if not most, do not possess immunity; that is, the carrier is immune, but the other members of the group are not. The bacteria can spread from person to person by direct contact (sharing food or drink or by kissing) or through the air by coughing or sneezing. This sets the stage for those without immunity to

develop a throat infection. From the nasopharynx these bacteria can enter the bloodstream, spread to the brain, and become meningitis. As it spreads from person to person, an epidemic of meningococcal meningitis occurs. This is probably what happened to you and your friends.

The incubation period is as short as twenty-four hours, so the epidemic spreads rapidly. By the time the first person becomes ill, many others are already exposed and will themselves become symptomatic in short order.

The major symptoms are fever, chills, sore throat, severe headache, stiff neck, photophobia (irritation of the eyes with exposure to light), generalized aches and pains, and nausea. Since it is an infection of the brain, lethargy, disorientation, confusion, and even coma can occur. This may explain why you remember little of the event.