Multiverse: Exploring the Worlds of Poul Anderson (45 page)

Read Multiverse: Exploring the Worlds of Poul Anderson Online

Authors: Greg Bear,Gardner Dozois

“Your explosives will not work,” she sent Fraq on a narrow squirt beam.

“I have scented this,” he said tightly, gliding over the Ark’s horizon.

“Can I trust you to go inside with me?”

This he pondered, hanging beside the circular lock entrance. “I carry no further weaponry,” he said at last.

By that time Ruth was there. Instead of slowing, she glided directly into the lock. Fraq barked some surprised epithet and hastily followed her.

Intuitively she sensed it was better to confront him inside, isolated; make it personal. She passed through an iris that opened at her approach. No air, but she was in a large space that slowly . . . awakened.

Phosphorescent glows stretched across long walls. Transparent cases lit, showing strange bodies suspended in clear liquid. Intricate tiny slabs showed pale colors, light fluttering as if from a slumber. DNA inventories? She prowled the space, surrounded by an enormous bio data base. Slowly, it came to life.

Suddenly zero-grav flowers floated by, big blooms growing from spheres of water. She recalled as a girl watching the joy of soap bubbles shimmering in sunlight. These somehow sprang to life in vacuum.

Behind thin windows, gnarled trees like bonsai curled out from moistening soil. Odd angular plants burgeoned before her eyes.

In all directions of the cylindrical space, plants grew, looking to her like lavender brushstrokes in the air. In a spinning liquid vessel, orange snakes with butterfly wings danced in bubbling air.

Displays.

She heard her own gasps echoed, turned. Fraq hung nearby, eyes wide. “Is a display,” he said. “A welcome, it could be.”

“Welcome, yes. It’s a bio inventory,” she said. “Displayed as an explanation. As advertising.”

In his own suit bubble he waved a wing at images playing along the walls. Purple-skinned animals loping on octopuslike tendrils across a sandy plain. Flying carpets with big yellow eyes, massive ruddy creatures moving like mountains on tracks of slime, trees that walked, fish in stony undersea palaces. A library of alien life.

She turned full on to him, pressed against his bubble, glowered. “What was that you said? The Ark was a ‘Prime Need for life itself’ eh?”

“We came for ancient vengeance,” Fraq said stonily over comm, tan feathers ruffling with unease.

“For what? They sent you an Ark? But—”

“And we brought their life from the Ark in orbit, down to our world.” His eyes flared. “We could not control it. Did not know. Their strange creatures festered, escaped from us, attacked our life at every level. Diseases, blight, desolation, death. They nearly killed and colonized our biosphere.”

Sudden deep anger boiled in his tight voice. She sighed. “You . . . you just did it wrong.”

“They sent it as a weapon, our history says. Our foremothers laid down for all generations, as bloodpride, the call—to destroy all Arks.”

“It was too late to kill the Furians?”

“Alas, yes. Their star had eaten them.”

Suddenly, from the troubled shifting of his eyes, she saw why Fraq had insisted that she fly with them. First, to test whether humans could be better than the mere dirt-huggers of their world. Second, to show that Ythrian hunting carnivore life was hard, aloof, clannish.

That was all their way of telling me about themselves. And now I sense them. Intuit them. I know them beyond language.

The Ythris learned through experience, not from libraries. They had now to think of this Ark as repository of lost history, not as enemy.

She peered through the glassy bubble suit, reading his shifting feather patterns. “I’m sorry, but you should know more biology. Try experiments! Don’t bring in invasive forms until you understand them. Look—” she gestured wide at the bounty surrounding them. “They’re

offering

, not invading.”

Fraq’s stiff face slowly eased. Feathers rustled. “I was charged with bringing destruction. My kind regrets that you knew more, and deadened our explosives.”

“We know more about war, unfortunately. Look, that’s over. Question is, what next?”

“You must destroy this.”

“Hey, I’m a librarian! Don’t destroy, study! Learn!”

“It is a danger too vast to say.” He frowned darkly. “This is a matter of bloodpride.”

“We’ll learn from your mistake. No Furian life gets into Earth’s biosphere. Or those of Mars and Luna.”

“I will consider it.” More feather riffles, hard to read.

“You’ve already

seen

how we’ll do it,” Ruth said suddenly, the idea fresh born and irresistible. “This ship is live now. Let’s redirect it. Send it to Luna, use the bolo to bring some of it down. Carefully take bits of the Furian life into a huge new void, specially dug. Create an alien biosphere isolated by a hundred kilometers of rock.”

Fraq blinked. She could see his Ythrian male rigidity ease a bit, muscles soften, breathing slow. She had been studying his body language and now somehow knew how to work with it.

She could do this.

No Prefect need get in the way, either. Just her and this beautiful alien.

She smiled. Wordless, the two of them hung in the luminous center of ancient legacy, a Library of Life for an entire world now gone forever.

They

could do it.

Her heart beat faster. She watched his strong wings flex with new energy as the idea took hold.

Y’know, he does look like a great guy . . .

AFTERWORD:

In January 1999

Poul Anderson sent me a letter enclosing his essay on his invented aliens, the Ythrians, which he had used in his novel,

The People of the Wind.

I had liked the novel and had asked him as part of a proposed anthology for details on the planet and its aliens. My notion was a collection of stories that dealt with aliens in scrupulous detail, attention paid to how they evolved, how that affected their worldview, and how humans might react to them. Maybe there would be humans in the stories, maybe not.

The anthology idea didn’t fly, alas. Poul was a meticulous writer, working out an integrated vision for a novel, though few of these manuscripts apparently saw print. He was ready to write another story in one of his worlds, and it was a singular treat seeing how he had designed it.

Approached to contribute to this volume, I fetched out his thirteen page Ythri description, with solar system and planetary parameters in detail. His essay also included several of his sketches of these aliens and their anatomy, even diagrams of their wing bones and skull. He named the planet Ythri, which I’ve used for its natives. It’s a world with 0.75 Earth’s g and a denser atmosphere, both explaining how smart-flying aliens could evolve. His body plans and physiology proceed from solid constraints, including their body mass (30 kg) and molecular chemistry. There are words for local plants and crops and domesticated

animals. I’ve kept his details and terms, with some small alterations to fit my story.

From his parallel short story, “Wings of Victory,” I’ve taken some Ythri culture, speech, and attitudes, and even phrases Poul made up in their language. Poul worked out and wrote up in great detail far more than he used, a signature of the Hal Clement school of planet-building, as admirably shown in Clement’s founding novel of the school,

Heavy Planet

. I altered the Ythri history somewhat to fit, but kept their nature the same.

Further, I wrote from the viewpoint of a character and situation I’ve been developing in a story series about what a SETI Library might look like when we have a host of messages to work through. While coded signals would be fascinating, it’s always more fun to have a live alien in the foreground, too.

Poul was a major player of the game among hard SF writers: judge if these ideas pass muster, and see what I’ve done with them. I knew Poul since 1963 and treasured the many times we met, dined and drank together. I miss him greatly, and it’s been a pleasure to play in one of his imagined worlds.

—Gregory Benford

THREE LILIES AND THREE LEOPARDS

(And A Participation Ribbon In Science)

by Tad Williams

Tad Williams

became an international bestseller with his very first novel,

Tailchaser’s Song,

and the high quality of his output and the devotion of his readers has kept him on the top of the charts ever since as a

New York Times

and

London Sunday Times

bestseller. His other novels include

The Dragonbone Chair, The Stone of Farewell, To Green Angel Tower, Siege, Storm, City of Golden Shadow, Otherland, River of Blue Fire, Mountain of Black Glass, Sea of Silver Light, Caliban’s Hour, Child of an Ancient City (

with Nina Kiriki Hoffman

), Tad Williams’ Mirror World: An Illustrated Novel, The War of the Flowers, Shadowmarch,

a collection

, Rite: Short Work

,

and a collection of two novellas, one by Williams and one by Raymond E. Feist,

The Wood Boy/The Burning Man.

As editor, he has produced the big retrospective anthology,

A Treasury of Fantasy.

His most recent books are two novels in his Bobby Dollar series

; The Dirty Streets of Heaven

and

Happy Hour in Hell.

In addition to his novels, Williams writes comic books, and film and television scripts, and is co-founder of an interactive television company

.

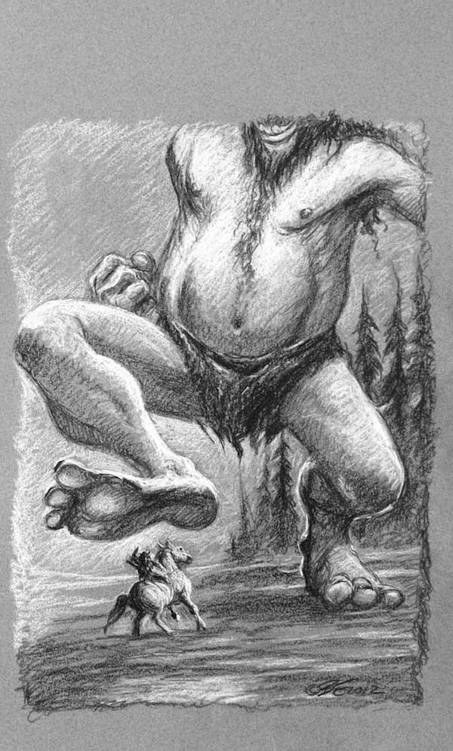

Here, due to a cosmic screwup, Fate sends the wrong person from our world into the world of Poul Anderson’s

Three Hearts and Three Lions,

with disastrous, and very funny, results

.

“Don’t freak out,

Fernando,” Pogo told his assistant manager. “I’m just going to the food court. You’ll be fine.”

Little Fernando tried to smile but it was the sickly grimace of an infantryman ordered to charge a machine gun nest. He pointed with a shaking finger at the crowd of bargain-hunters that had turned Saturday afternoon at Kirby Shoes into a battle zone. “But it’s the Summer Madness Event . . . !”

Perry Como Cashman, who had been named after the singer by a soon-to-be-absent father and had been called “Pogo” by his friends since junior high school, sighed. “I know, dude. But I haven’t been out of the store since I opened at seven this morning and I haven’t eaten anything and I’m

starving

. Little Ed’s back from his break and Big Ed’s here and whatsisname—you know, Stockroom Dude—can help out if you really need another body. I’ll be back in, like, twenty minutes max, so just hold your water.” Pogo patted Fernando on the shoulder. “I’ll bring you back something if you want.”

Fernando’s eyes were showing whites around the edges. “A gun or a knife, please. That lady threw a hiking boot at me!”

“Emergency!” shouted Little Ed from the other side of the store. “There’s a woman climbing the display wall, trying to get the last set of kids’ Adidas! Oh, man, she just clubbed somebody with a Brannock device . . . !”

Pogo was whistling as he made his way across Victory Plaza Mall. It had been a serious pleasure to leave Fernando and the others to deal with this latest crisis. For at least the next few minutes, the only thing he had to decide was whether he wanted cashew chicken, egg rolls, or both.

As he circled an ornamental fountain full of splashing toddlers, he thought he heard someone calling his name. He did his best to ignore it, but a few moments later he heard it again—

felt it

might be more accurate, since it was so faint, so distant. He turned with a grunt of irritation, expecting to see Fernando or one of his salesmen chasing after him, but saw only the usual afternoon shoppers, bored young mothers and seniors avoiding the San Fernando Valley heat in the air-conditioned mall.

Pogo . . . ! Pogo Cashman . . . !

He turned in a full circle, but nobody was even looking at him, let alone calling him.

Hunger hallucinations,

he thought.

Better get some pot stickers, too . . .

Pogo

. . . !

This time the voice sounded so close he whirled, expecting to find some practical joker standing right behind him, but he was alone in the center of the shopping center concourse. An instant later, he fell through the floor, tumbling through the very fabric of reality and into a darkness that throbbed with honks and squeals like a prog rock band tuning up.

He fell for a long time. Long enough to get bored.

I really wanted some egg rolls . . . !

was his last thought before he abruptly fell back into the world. The problem was, it was not the world that Pogo Cashman had fallen out of in the first place.

“Did ye do yersel’ a hurt, m’lord?” Small, rough hands pulled at him, trying to help him sit up. “Are ye wounded?”

Pogo was wondering about that himself, because everything sure smelled, sounded, and looked strange. Some shit had definitely gone wrong, either with the Victory Plaza Mall or Pogo Cashman himself. All the walls seemed to have fallen down and he was surrounded by trees instead of retail stores. Also, why was Fernando talking funny? And why was there a big, black horse standing just a few feet away?

“M’lord? What befell ye?”

“Fernando, you were supposed to . . . ” But then he realized it wasn’t his diminutive assistant manager standing over him but someone quite different—in fact, the stranger made little Fernando look like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He was a dwarf, with a nose like a brown avocado, a bushy, dirty beard, and large bare feet.

“Who are you?” Pogo asked him. “And how did I get to Disneyland?”

“I ken that land not,” the small fellow said. “But ye know me sure, lord. Ludo, yer ain sworn vassal.”

Pogo was really beginning to worry now. He had never had the greatest imagination (except during his youthful days of pharmaceutical exploration) and if he was imagining all this, that had to mean a pretty severe head injury.

And I never got my lunch, either

, he thought sadly.

Now I’ll probably spend months eating hospital food.

“Okay, Lou,” he said, trying to be a good sport. “Then if this isn’t Disneyland, where are we?”

The dwarf frowned, obviously concerned. “The forest of the Ardennes, Duke Astolfo. Sure ye must recollect!”

“Duke Astolfo?” The name was sort of familiar—a relief pitcher for the Angels, maybe? Professional surfer? “Hey, should somebody call an ambulance? Because I think I might have a brain injury or something. Or could you kind of steer me back to the mall, at least? I manage Kirby Shoes—you know it? Across from Orange Julius, next to J.C. Penney?”

Ludo shook his head. “This is nay guid and the dark will soon come. We maun make camp.”

“Yeah. So is there a snack bar or a store or something around here? A minimart? ’Cause I never got any lunch today.”

But the dwarf only shook his head again and helped Cashman to his feet. He was stronger than his size would have suggested. “Can ye ride, m’lord?”

“On a horse?” Pogo examined the huge, black beast. Horses didn’t look anywhere near so big on television. “I don’t know. Is it hard?”

Supervisor Fnutt had called a sudden and mandatory meeting for all management personnel. Even sub-sub-manager Quidprobe, the new kid in the office, knew that had to be a bad sign.

All the dozens of managers and sub-managers of the Crossover Division of the Department of Fictional Universes were crowded into the conference space, although most of them looked as though they would rather be pretty much anywhere else. Fnutt the supervisor was pacing back and forth at the front of the room—or what would have been the front if the Department of Fictional Universes had been in any way compelled by Euclidean geometry.

“This is bad!” Fnutt squealed. The supervisor was a small green fellow with a small green mustache and a tendency to become shrill. “Very,

very

bad!” At the moment, he was in danger of shattering every coffee cup in the room. “How could this happen?”

“Does it matter?” asked Bardler, who managed the Matter of France, his tone heavy with doom. “It’s happened. It’s too late now to do anything but watch the destruction!”

Quidprobe, a sub-sub-manager in the Poul Anderson subdivision, with untaxing maintenance duties in the seldom-accessed Ariosto section of Anderson’s Matter of France, raised a rubbery, three-fingered hand. “I still don’t understand what happened.”

“One of your boss Digry’s idiot clerks sent the wrong personnel request,” Bardler snarled, “and so some idiot named Cashman—a shoe store manager, no less!—was dispatched to Anderson’s medieval France for a tricky assignment, instead of the guy who was supposed to go, Porter Gervaise Castlemane, an English chemical engineer and former SAS officer.” Bardler scratched both his noses. “Who would have been perfect by the way. Castlemane can kill a man with just his

fingertips

.”

“Yes, we sent the wrong initial request,” bubbled Quidprobe’s boss, Digry, “but then one of

your

idiot clerks didn’t see our Correction Form!” Digry was so upset his face was pressed against the window of his tank and his nicitating membranes snapped up and down like windshield wipers in a deluge. “We spotted the mistake in moments. We sent the proper MP-362A immediately. But someone in your office must have been taking a nitrogen break.”

Bardler didn’t seem to have an argument at the tip of his feeding tube, so he just scowled.

“

Stop!

We’ll figure out what went wrong later!” Supervisor Fnutt was getting dangerously squeaky again. “Right now we have to think of something to do about this . . . catastrophe!”

“Can’t we just reverse it?” asked Quidprobe. He’d been less than a century on the job—very young by departmental standards—but he was ambitious, as the young often are. As far as he could tell, the other managers uniformly loathed him for it.

“It doesn’t work that way,” screeched Fnutt, his mustache writhing like a caterpillar on a griddle. “Departmental regs say that once the personnel unit has been transferred into the fictional world, any change of plan has to go to the top for approval. The

very, very top.

” Just the look on Fnutt’s face was enough to make even the most hardened of department employees moisten with fear where his, her, or its limbs attached. “So either we call the big boys right now and tell them we have royally screwed the tetramorph or we have to leave him there.”

“And if we leave him there, everything else will go wrong,” said Bardler darkly. “Roland will stay insane. Nobody will save Charlemagne from Agramant and Aelfric. Christendom will totter and fall.”

“But it’s only a crossover story about the Matter of France, one of Anderson’s old books—in fact, what we’re dealing with here isn’t even an actual story by Poul Anderson!” said Quidprobe. “I was looking over the order this morning. It’s only some kind of pastiche for an anthology based on his work—and not very closely based, either, I couldn’t help noticing. I suspect the guy writing it is a bit of a hack. So who cares?” But when Quidprobe saw the look on the faces of his superiors his cheerful smile faltered and he blanched right down to his basal chromatophores. “Uh . . . what don’t I understand?”

Supervisor Fnutt was clearly doing his best not to lose his temper, but some of the more veteran managers looked like they were already wondering if they would get time off to attend Quidprobe’s funeral. “Listen . . .

youngster.

What you don’t understand is that when something goes wrong enough with an important creator like Anderson’s version of a world, the problem will ripple out from there.”

“Ripple?” Quidprobe looked around.

“It means, you bottom-hole-breather,” growled Bardler, “that when this Cashman guy fails, it’ll infect the entire Matter of France. The whole thing! Not just Anderson’s version, but Ariosto, the Song of Roland—which is, incidentally, the oldest surviving piece of French literature—and who knows what else.” Bardler was getting angrier as he spoke, and Quidprobe was now doing his best to slide under the table, but fear had made the sub-sub-manager rubbery and he was going horizontal as much as vertical. “A few weeks from now,” Bardler shouted, “Charles the Great will probably be known as Charles the Loser!”

Even Quidprobe’s boss Digry looked anxious. “That bad? Really?”

“You knock the pins out from under Charlemagne and after a little while, there goes Arthur and the Round Table, too!” Bardler declared with a certain grim satisfaction. “And then—goodbye, English literature! Farewell, Western European Humanism!

So long, it was fun! Write if you find work!

”

“Enough!” squeaked Fnutt.

Bardler dropped back into his chair and subsided into scowling silence. All around the long table managers and sub-managers shifted uneasily, thanking whatever they prayed to that they were not in Quidprobe’s now rather viscous seat. In fact, Quidprobe wasn’t in it either: he had finally managed to slither onto the floor.

“It’s your orb and your game now,” Fnutt told them with dark finality. “As far as I’m concerned, this meeting never happened. And when I’m ready to send my report at the end of the day, I don’t want to see any loose ends that I’ll have to report to . . .

you know who.

” Fnutt rose to his full, if unprepossessing height, and marched out of the conference space, followed a moment later by his mustache.