Multiverse: Exploring the Worlds of Poul Anderson (14 page)

Read Multiverse: Exploring the Worlds of Poul Anderson Online

Authors: Greg Bear,Gardner Dozois

He had been a member of MWA before SFWA existed, and was familiar with their motto: “Crime does not pay—enough!” As a founding member he had agreed that it must, like MWA, be not a literary society but an organization of professionals. Poul worked hard to support it. He was elected one of its first presidents, and served two terms, missing deadlines for the first time. I had made sales enough to join the organization along with him, and paid my dues regularly, though my solo sales were few. Eventually we bought life memberships.

In 1966, after that year’s Worldcon, we took part in the Milford Writers’ Conference hosted annually by Damon Knight and Kate Wilhelm at their home. Participants benefited from critiquing each others’ stories, and also from extended discussions, going beyond those that took place at Worldcons. We thought SFWA would profit from a similar annual get-together. Next spring, we put on the first annual SFWA Awards gathering. Astrid and her “twin” were our support staff, handing out badges and suchlike. (I was very proud in 2004 to see how well Astrid ran the weekend in Seattle.) We continued, in spite of the sometimes furious internal controversies, to support the organization in every way we could.

When Poul received his Grand Master award at Santa Fe, instead of having a typed acceptance speech he spoke extempore. I wish someone had been recording the proceedings, because he spoke of me and all the ways I’d assisted him through the years. He ended with the words, “She is my love.”

DANCING ON THE EDGE OF THE DARK

by C.J. Cherryh

C.J. Cherryh

is the author of more than sixty novels, the winner of

the John W. Campbell Award and three Hugo Awards, and a figure of immense significance in both the science fiction and fantasy fields. In science fiction, she’s published the thirteen-volume

Foreigner

series, the seven-volume

Company Wars

series, the five-volume

Compact Space

series, and many other series and stand-alone novels, including

Cyteen.

In fantasy, she’s the author of the four-volume

Morgaine

series, the three-volume

Rusalka

series, the five-volume

Tristan

series, the two-volume

Arafel

series, and, as editor, the seven-volume

Merovingen Nights

anthologies

.

Some of her best-known novels include

Downbelow Station

,

The Pride of Chanur, Gate of Ivrel, Kesrith, Serpent’s Reach, Rimrunners, The Dreamstone, Port Eternity

,

and

Brothers of Earth.

Her short fiction has been collected in

Sunfall, Visible Light,

and

The Collected Short Fiction of C.J. Cherryh.

Her most recent book is a new novel in the

Foreigner

world

, Betrayer.

She lives in Spokane, Washington.

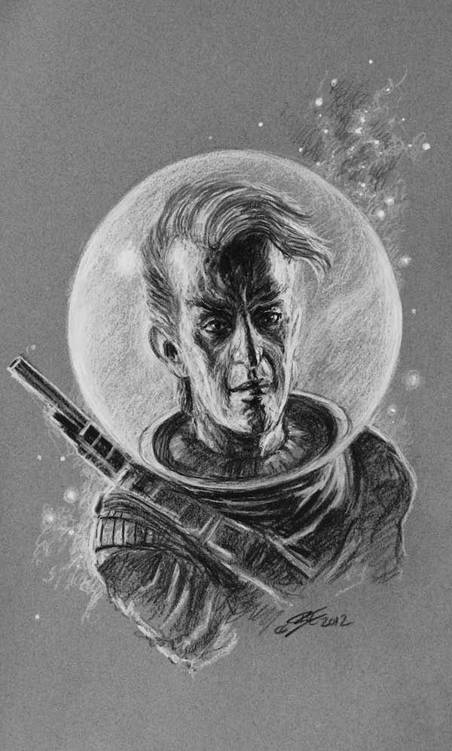

Swashbuckling but ruthless Imperial agent Dominic Flandry, who works tirelessly to prevent the Terran Empire from falling, although he knows that the interstellar Dark Age that will follow the Empire’s collapse inevitably will come someday in spite of his best efforts, may be Poul Anderson’s single most popular character. Flandry’s first adventure was published in 1951, and he subsequently featured in six novels and enough shorter works to fill two collections, stretching across Anderson’s entire career. Dominic Flandry is occasionally referred to as “science fiction’s James Bond,” but the fact is that Flandry started his adventures two years

before

James Bond made his fictional debut, so perhaps James Bond should instead be referred to as “the mainstream’s Dominic Flandry!”

Here, C.J. Cherryh gives us a new generation of Flandrys setting up shop in the family business . . .

The Empire

was frayed on the edges. There had been the business in Scotha, and there had been so many others besides, wars, conquests, collapses, rebellions . . . all, all in constant motion. The Galaxy was wide. The reach of ships grew, without the presence of enough Empire force to police the territories they opened up, and there was no shortage of other lordlings and dictators with ambitions and fleets.

The Terran Empire had been potent once—at least in concept. The Empire had thrown its perimeter wider and wider, incorporating the foreigners, the odd, the strange, the different—and the occasionally incomprehensible.

Success had widened its boundaries so very far now there was no way, now, that all of the Empire could be attacked at once.

But neither could it be defended, even piecemeal, and moving assets about to deal with brushfires in the hinterworlds grew harder and harder for the Empire to deal with. There was an incursion in the double sun system, on the desert moon of Lothar, which needed a fleet to deal with it, and the Empire dealt with that—bringing in a hundred ships from Audette; but moving forces from Audette encouraged Duadin to move on its neighbor, and while all that was going on, over on the opposite side of the Empire, the Succession Wars of Patmai broke out, which simply could not be addressed.

The winner of that struggle took a sector out of the Empire, and the Empire, for once, had to sigh collectively and say that rebellions were short and tyrants had lifespans—while the Empire was long, and had a long memory for former situations. It meant to bring Patmai and Patmara back into the Empire.

It would—perhaps—do that, when it found the time. And when it was convenient.

Meanwhile the Mersians, old allies, conspired at overthrow, in yet another direction.

One thing happened, and another, not far apart.

That was the way the Empire ebbed a little from certain shores, even while still advancing on others. That was the way that, here and there on its edges, more small fires sprang up, put out if convenient, allowed to burn down in isolation if not—sometimes peeling a world away for a while, or longer.

The fact was the Empire had become like an old cloth fraying from wear at the edges—and if ever a young, strong and hungry force such as it had once been should brush up against it now, the Empire would be in the direst difficulty, unable to muster all its scattered parts to its own defense.

Therefore the Empire feared the borders it once had thundered out to expand and expand and expand . . . while its secret heart grew weaker.

Fear became its own war of attrition. Policymakers at the heart of the Empire feared the motives of those who came from those border worlds. It was easy, safe politics, to blame every ill on the barbarians, so as not to have to examine the rot at the heart of things that still functioned tolerably well, as the center of Empire saw it. The status quo became the rule, and woe to him who disturbed it.

Nowadays the Empire felt safer with less forceful governance, and mistrusted local authorities who pointed to distant or future causes of trouble—or worse, local officials who suggested doing something about them. The powers of the Empire listened to nothing that would mean real revision of the Way Things Were.

That philosophy had gone on a long, long time, in a state of slow drift, slow rot.

But in the way of old Empires, once the heart began to soften, once certain strong-willed people living their lives out between the rotten core and the frayed edge began to understand that the Long Night could come down on them in their lifetimes, they found

they

had not been in the Empire long enough to be philosophical about it all.

They

were

inclined to fight against the Long Night.

And they might

be

barbarians, a generation back, but they had committed everything to the existence of the Empire. They saw the good in it, and they saw the alternative far more clearly than the denizens of the capital could see it—the red age, the blood age, the forever-dark to follow, with fire and with killing. They had fought their way out of it—and they were not ready to sit still and slide back into it.

So they stiffened their backbones and sharpened their wits and determined that an Empire rotten at the heart

could

survive, if wit and courage of its outliers stiffened resistence all about it. They would become the armor keeping an old, old creature alive and whole.

Dominic Flandry had bent events in the Empire’s favor. In an action fairly minor as the Empire viewed things, he had set up barbaric Scotha as a new and progressive part of the Empire, weaving a new patch onto an old situation. He had outwitted, outmaneuvered, and outplanned the opposition; he had set a new ruler on the throne, which had definitely been important for the Scothan Sector, and for the Hydran Quadrant which contained it. Where Dominic Flandry was now—whether he had gone off to the far edges of the Empire to devise some clever solution for its woes in another direction—possibly dealing with the Patmara affair, or the Mersians—no one locally knew.

But there had grown up a little cabal in the academy at the heart of the Hydran Quadrant, on this side of the Empire.

Four young diplomats belonged to this odd group. They were four very diverse individuals, a man and three women, classmates, or at least their academic careers had somewhat overlapped, and they found common interests and a common philosophy, in this artificial world distant from all their origins, working in the diplomatic service in various capacities. They all had a last name—not universal in the Empire, and it was all the same name, which was not at all as common as, say, Smith, Ngy, or No’b’Ar-Grisigis.

In this case, it was a name of legend in the Quadrant. The last name was Flandry, and it was

not

a common name in Scotha Sector, or Mardier Sector, or in Lussanche, or in Modi, or anywhere about these parts.

These four were human—well, mostly so. The junior of the four was a brown-eyed lad, all human, with a mop of ringlets and, lately, a mustache—the three senior were women, had ringlets more or less original, one short-cut and red-brown, one long and lustrously dark; and one, well, the hair had been white-blond from the start and the owner refused to say whether it was original, but one suspected . . . and the eyes—well, the

eyes.

All the lot of Flandrys had brown eyes except Audra, the young woman from Scotha, who had followed the fashion and had eyes as yellow as a G4 sun, a matter of some amusement to her half-brother and -sisters.

They all looked really not a thing alike—especially the yellow-eyed one, whose ears were somewhat odd, and whose brow had two dainty but distinct horns at the hairline.

They all were lightly built, not so tall—and as a group one would say they were a good-looking foursome, though they were not remarkable, not even the Scothian. But when you saw more than one of them sitting in a general meeting, or when they gathered, as they did once weekly, at The White Tree Pub, opposite the Quadrant Offices, you took a second glance.

Then if you’d ever known Dominic Flandry, you might take a third look, especially at the youngest, the young man, who was the very spit of the elder Flandry in his youth.

And when, deep in the secrecy of the Quadrant Offices, this four talked together, it sounded as light as their conversations in the pub, but life and death sometimes figured in it; and they talked about places on the edge of the great dark, and named names that should not be named elsewhere.

Not all of them had been on track for high positions in State. But the dark-haired eldest had been, and she had snared all the others. You wanted a favor from the State Department—she could do it.

And the blonde girl—Audra was her name, Audra Flandry, had come to

her

when she had needed the biggest of favors, and an assignment otherwise not likely to come to her.

“Heralt’s my brother,” Audra had said, showing a copy of a letter which had taken its sweet time getting to her. “Heralt’s

mine

.”

“You don’t want to

rule

Sotha,” the eldest had said.

Audra had shaken her head no, and yellow eyes flicked down and up, startling in their intent, under tilted brows. “No way do I want to rule Sotha. But I want this mission. I want a ship. I want everything I can get.”

Her mother, by a curious twist of fate, was Gunli, late queen of Sotha. Her youngest half-brother was Heralt, current king. And how that brother had gotten to be king was not a pleasant story.

“Your half-brother,” the eldest said, having read the letter—having, in fact, been the one to get it to her half-sister, “wants you to come back and marry one of his enemies.”

“His ally, actually.”

“An ally who’d betray him in a heartbeat. And you don’t certainly mean to go through with a marriage. With a barbarian lord who probably doesn’t bathe regularly—let alone accept Empire law?”

“I want a ship,” Audra said. “I’ve never asked a favor. I’m asking it now.”

The matter occasioned a meeting of the four, over tea, in a quiet, secure room, in Quadrant Central, and without the direct knowledge of persons highest-up in the Quadrant.

“You don’t want Sotha,” said another of the four. “And

surely

you don’t want to be queen of Wigan. So what are you thinking?”

Audra scowled. “That my half-brother is no fool.”

“No, more’s the pity,” the youngest said. “He’s ambitious, he’s just come back from exile and killed your uncle—”

“Who had it coming,” Audra said, and her face grew cold in contemplation of the history she knew. “Empire law wouldn’t let me deal with it. Not without resigning. And I wouldn’t. But—”

“But now you will?” the redhead asked, while the senior of them said nothing.

“No such thing. I have no intention of marrying the King of Wigan.”

“This half-brother—” the redhead said.

“I have every intent of dealing with this. I couldn’t, before. Now I have an appeal from

inside

Scothania.”

“That wants you to come back and marry a stranger who doesn’t bathe!”

Audra shoved back from the table. The youngest put out his hand and laid it on hers, calming.

“Audra’s entitled to have this mission,” he said quietly. “Audra could be Queen of Scotha if she’d wanted to.”

“Not just if I wanted to,” Audra said. “I could renounce the Academy and go—or go with that piece of paper

asking

me to come in.” She pushed away and walked to the side of the room, to the sideboard with its teapot, and poured a second cup, in silence.

“She has the right,” the dark-haired senior said. “She has the absolute right.”

“Trade a career the Empire for a planet with its problems?” the redhead asked, shaking her head. “I’m not fighting her getting a mission. I’m fighting her going out there and getting killed.”

“They killed her mother,” the young man said quietly. “Herse did. Killed her older brother. Killed the whole family except her mother got her out.”