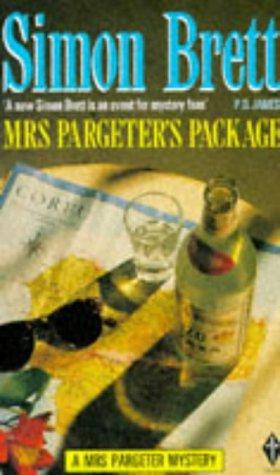

Mrs Pargeter's Package

Read Mrs Pargeter's Package Online

Authors: Simon Brett

CHAPTER 1

As the coach zigzagged through the darkness in a grinding of gears, Mrs Pargeter reflected that this was not her preferred style of travel. She knew that she had been spoiled by the late Mr Pargeter, but felt strongly that his insistence on first class facilities at all times had been more than mere pampering. Travel, it had always been his view, was a tedious necessity, the important part of any journey was what one did on reaching one's destination, and therefore the less strain the actual business of transportation involved, the better. The cost of attaining such comfort, however high, was money well spent. It had been particularly important in the late Mr Pargeter's line of work that he always arrived anywhere with all his wits about him.

However, one will suffer a lot in the cause of friendship, and it was a mission of friendship that had brought Mrs Pargeter to Corfu in these atypical circumstances. Joyce Dover, now tense beside her, peering anxiously through the coach window at the occasional light on the hillside, had been in a bad state when she first suggested the mutual holiday. Mrs Pargeter could not but sympathise; the void left in her own life by the death of the late Mr Pargeter was still a daily ache of melancholy; and Joyce had recently lost her husband, Chris. Though Mrs Pargeter had never met the man in question, she knew what her friend was going through, she knew how much nerve proposing the trip must have required, and had been happy to agree to the proposal.

She had offered to make the arrangements herself. As well as taking the burden of such details off her friend's troubled shoulders, this would also have ensured a level of resort and accommodation in keeping with her own – admittedly rather high – standards. Money never appeared to have been a problem for Joyce, but if there had been any difficulty, Mrs Pargeter would have been happy to subsidise her.

Joyce, however, had been adamantly opposed to this offer of help. Activity, she insisted, was the therapy currently required, and arranging a holiday would be an ideal distraction for her. She and her husband had never been to Greece, it was therefore an area without prompts to painful memories, so it was to Greece that they would go.

And before Mrs Pargeter had had time to drop a few hints about the parts of Greece she thought most suitable and the hotels she thought most comfortable, the bookings were made. A fortnight's package tour in early June to Agios Nikitas on the north-east coast of Corfu. Self-catering in the Villa Eleni.

Self-catering? It was remarkable, Mrs Pargeter reflected, what one would do in the cause of friendship.

So it was in the cause of friendship that she had turned up at Gatwick Airport two hours early to check in for their charter flight. It was in the cause of friendship that she had sat at Gatwick Airport for the five hours that that flight had been delayed. Friendship had made her pretend enthusiasm for plastic food in a cramped Boeing 727 full of screaming children, and friendship now found her shaken about in the back of the coach that wheezed along the switchback coastal road from Corfu Airport to Agios Nikitas.

But Mrs Pargeter did not repine or complain. Hers was a philosophical nature. Life with the late Mr Pargeter had taught her not to set too much store by anticipation. Don't waste energy in fear of the future, he had always said. Wait and see what happens, and when it does happen you'll be surprised at the resources you find within yourself to cope with the situation.

So Mrs Pargeter smoothed down the bright cotton print of her dress over plump thighs, let the warm air from the coach window play through her white hair, and waited to see what the next fortnight would bring.

CHAPTER 2

'Could I have your attention, please?' The tour rep, who had identified herself in a fulsome English girls' public-school accent at Corfu Airport as 'Ginnie', shouted above the groaning of the coach's engine.

It took a moment to get the attention of all the party. After the discomforts of their journey, and in spite of the lurches of the coach, a good few had dozed off. Keith and Linda, the young couple from South Woodham Ferrers in Essex, who had just got their eighteen-month-old Craig off to sleep, complained of the interruption. Mrs Pargeter, who had provided Craig with an unwilling target for airline-food-throwing practice during the three-and-a-half-hour flight, also regretted his return to consciousness.

'Sorry,' said Ginnie, in a voice that didn't sound at all sorry. Presumably she too was feeling strained after five hours waiting for them at Corfu Airport. 'I just wanted to say that we are very nearly there. In a couple of minutes, we turn off the main road down to Agios Nikitas. I should warn you, the track down to the village is pretty bumpy.'

'What, bumpier than this one? Must have more bumps than the mother-in-law's car,' said the retired man in the beige safari suit, who at Gatwick check-in had appointed himself the life and soul of the party. Mrs Pargeter had decided at the time that a little of him would probably go a long way; the total lack of reaction to his latest witticism suggested that ten hours in his company had brought everyone else round to the same opinion. Even his weedy wife, in matching beige safari suit, was unable to raise the wateriest of smiles.

'Anyway,' Ginnie continued, 'because we're rather later in arriving than we expected . . .' – grumbles of the you-can-say-that-again variety greeted this – 'and you may be hungry . . .' – this was endorsed with varying degrees of enthusiasm – 'when we get to the village, some of you may want to go and have something to eat, and others want to go straight to your accommodation. So what we'll do is stop first at Spiro's taverna and offload those who want to eat, while the coach'll take the rest to their villas.'

'And what'll happen to the luggage of the taverna party?' asked Mrs Safari Suit.

'It'll be delivered to the villas. Be quite safe there till you've finished eating.'

'That's a relief,' said Mr Safari Suit, and then slyly added, 'Cor! Phew!' The pun had elicited only minimal response when he'd first used it in the Gatwick departure lounge. Now, on its eleventh airing, it got no reaction at all.

'Er, excuse me, Ginnie,' asked Linda from South Woodham Ferrers, 'you mention Spiro's, but there is more than one taverna in the village, isn't there?'

'Oh yes, there's Spiro's and there's The Three Brothers and there's Costa's and the Hotel Nausica. Try them all by all means, but, er, the general consensus of clients who have been here over the years is that the atmosphere at Spiro's is the best. And the food, actually.'

'Do they all have Greek dancing?' asked the Secretary with Short Bleached Hair.

'Yes, there's Greek dancing most nights, and then each taverna has a party night every week. Special menu, dancing displays and so on. Costa's has his on Friday, the hotel on Saturday, Spiro on Monday and The Three Brothers on Wednesday.'

'Oh, right, we'll try Costa's tomorrow,' said the Secretary with Short Bleached Hair to her friend.

'And are there any nightclubs?' asked her friend, the Secretary with Long Bleached Hair.

'Not nightclubs as such. Not in Agios Nikitas – though of course things go on pretty late in the tavernas. If you want proper nightclubs, you have to go along the coast to Ipsos or Dassia.'

'Oh, right, we'll try that Saturday,' said the Secretary with Long Bleached Hair to the Secretary with Short Bleached Hair.

Having fielded this flurry of questions, Ginnie turned to the coach driver and said something in fluent Greek. He laughed, though whether at the expense of his passengers or not was hard to tell.

'God, I hope we get there soon,' muttered Joyce, as the coach lurched off the main road on to a pitted, stony track. 'I'm desperate for a pee.'

'Won't be long now,' said Mrs Pargeter, in her comforting, slightly Cockney voice.

'And for a drink,' said Joyce. Her small face was tight with anxiety beneath its spray of blonded hair.

The desperation for a drink sounded greater than that for a pee. Mrs Pargeter had a moment of worry. She knew that anything offering temporary oblivion was seductive in the first bleak shock of widowhood, but her friend did seem to be giving in too readily to the temptations of alcohol. Joyce had kept going with gin and tonics through the long wait at Gatwick and taken everything she had been offered on the plane.

And then there had been that strange business with the package . . . Before they went through to the departure lounge, Joyce had suddenly asked Mrs Pargeter if she had room in her flightbag to carry something for her. 'Not that it's too heavy or anything, Melita, just don't want to be over the limit if I'm stopped by Customs.'

The package that had been handed over, and that still resided in the flightbag under Mrs Pargeter's seat, had been stoutly wrapped in cardboard and brown paper, but the way its contents shifted left no doubt that it contained a bottle. The need to take her own supplies into a country where alcohol was as readily available as Greece suggested that maybe Joyce did have a bit of a 'drinking problem'.

But her caution about the Customs had not been misplaced. The grimly-moustached officer at Corfu Airport had singled out the fifty-five-year-old Joyce, along with a couple of more obvious student targets, and insisted on her opening suitcases and flightbag. Despite a detailed search, he found nothing that he shouldn't and the suspect was allowed to go on her way.

It did seem strange, though . . . And now Mrs Pargeter thought about the incident, she realised that the Customs officer had not found any other bottles in her friend's luggage. So why had the package been given to her? What had Joyce meant about the danger of being 'over the limit'? That was even stranger.

Mrs Pargeter was interrupted by Ginnie's voice before she had time to ask Joyce for an explanation. 'Right, everyone, as we turn the corner here, we'll be able to see over to Albania. Nobody quite knows what goes on in there, so a word of advice . . . if any of you are renting out boats during your stay, don't go too close to their side, OK?'

The passengers turned to look out over the void of sea to the distant lights. A large brightly-illuminated vessel moved slowly up the centre of the channel. The atmosphere in the coach changed. Now they were so close to their destination, excitement rekindled for the first time since that distant half-hour at Gatwick before they had heard about the flight delay.

'And down the bottom of the hill there you can see the village.'

They rounded the last corner. Light spilled from the seafront tavernas and villas on to the glassy arc of a little bay. Reflected bulbs winked back from the water to the strings of real bulbs above them. At their moorings bobbed motorboats, four carbon-copy yachts from a flotilla, and sturdy fishing boats with large lamps on the bows to attract their night-time catch. Some of the older fishing vessels had eyes painted either side of their prows, luck-bringers designed to outstare the Evil Eye, a phenomenon which still had its believers on Corfu.

The road ran between the buildings and the sea. Wooden piers thrust out into the water opposite the taverna entrances. At one a stout blue caique was moored.

The coach scrunched to a halt outside a large rectangular stone building over the front of which a striped canvas awning was stretched. Beneath this, tanned holiday-makers in T-shirts and shorts sat over drinks and food, paying no more than desultory attention to the new arrivals. The sound of recorded bouzouki music, together with a smell of burning charcoal and herbs, wafted in through the coach's windows.

'At last,' said Ginnie. 'Welcome to Agios Nikitas.'

CHAPTER 3

'I really am desperate now. Must find the Ladies. You get a table, won't you, Melita?'

'Yes,' Mrs Pargeter called after Joyce's retreating back, before picking up her flightbag and moving at a more sedate pace out of the coach. She saw Joyce hurry into the stone building, only to re-emerge a few seconds later, redirected round the side where a painted notice with an arrow read 'Toilets'. It seemed that language wasn't going to be a problem in Agios Nikitas.

This impression was endorsed by the greeting of the tall man who rose from a roadside table to greet the coach party. 'Welcome to Spiro's,' he said expansively. 'Here we will give you good time. Good drink and food to relax you after your journey. Ask Spiro what you want – anything – no problem.'

He was olive-skinned, in his fifties, but well-preserved, with muscular shoulders. Despite his bonhomie, a latent melancholy lurked in eyes that gleamed like black cherries under bushy eyebrows. The hair on his head was dusted with grey, but it still grew black in the 'V' of chest exposed by his open white shirt. He wore waiter's uniform black trousers and shoes, but carried an air of undisputed authority. He snapped fingers at the younger waiters to have the newcomers distributed to tables and drinks orders taken. From the doorway to the taverna he orchestrated the distribution of this first round, and within moments everyone had been served with glasses and bottles sweating from the fridge.

The orders had varied. Half-litres of lager, bottles of Greek white wine, Cokes, a fizzy orange for Craig from South Woodham Ferrers, a few traditionalists' gin and tonics, a couple of more daring ouzos. Mrs Pargeter, safely ensconced at a table for two with her flightbag stowed beneath the seat, did not know where Joyce had reached in her alcoholic cycle, but was in no doubt about what she herself wanted to drink. The Pargeters had developed an enthusiastic appetite for retsina on Crete, where they had spent three months after one of the late Mr Pargeter's more spectacular business coups. An all too rare sustained period of conjugal togetherness, Mrs Pargeter recollected fondly.

By the time Joyce returned from the Ladies, the coach had departed with Ginnie aboard to supervise the disposition of luggage and tired tourists, and Spiro had disappeared inside the building to supervise food orders. Joyce looked flushed and anxious, and had certainly been gone a long time. Mrs Pargeter hoped that her friend wasn't ill. There was something disturbingly jumpy in her manner, but maybe it was no more than continuing reaction to her bereavement.

'Loos are spotless,' Joyce announced as she sat down.

'Oh, good. You all right, love?'

The concern was waved aside. 'Yes, yes. Have you ordered me a drink?'

'Wasn't sure what you wanted. Try some of this?' Mrs Pargeter proffered the retsina bottle.

Joyce sniffed the contents and grimaced. 'No, thank you.' She looked round and was immediately rewarded by the approach of a young waiter, carrying paper cloths and a metal holder for oil, vinegar, salt, pepper and toothpicks. 'Could you get me a drink, please?'

'Yes, please.' Deftly he lifted the retsina bottle and glasses, slipped the paper cloth under them on to the polythene-covered table top and snapped its corners secure under elastic cords. 'What you like, please?'

'An ouzo.'

'An ouzo, of course, please. No problem.'

'Thank you. Can I ask what your name is?'

'Name, please? I am Yianni, please.'

He flashed an even-toothed smile and whisked away, his improbably slim hips gliding easily between the tables.

'Hm, how do you get one like that?' Joyce asked wistfully.

'I hadn't thought of you as on the look-out for a toyboy,' said Mrs Pargeter.

'Chance'd be a fine thing. No, first time in my life that I'd be free to have a toyboy, and now I'm fiftysomething and stringy, so nobody's going to be interested.'

'Oh, well . . .' Mrs Pargeter shrugged philosophically. 'That's the way things go. I once heard someone say that experience is the comb life gives you after you've lost your hair.'

'Sickening, isn't it? Trouble is, Melita, when you actually do have the freedom, you don't realise it. 1 mean, when I was about twenty I could have been having a whale of a time, lots of affairs, no strings, but did I? No, I just spent all my time worrying because nobody appeared to want to marry me. Didn't you find that?'

'Well, not exactly.' Mrs Pargeter didn't really want to elaborate. In fact, she had had a vibrantly exciting sex-life before she met the late Mr Pargeter – and indeed a vibrantly exciting sex-life throughout their marriage – but she had always believed that sex was a subject of exclusive interest to the participants.

Joyce was fortunately prevented from asking for elaboration by the arrival of Yianni with her ouzo. She diluted it from the accompanying glass of water, watched with satisfaction as the transparent liquid clouded to milky whiteness and took a long swallow, before continuing her monologue. 'Conchita's just the same as I was. I mean, there my daughter is, lovely girl, early twenties, successful career, could have any man she wants, and what does she do? She keeps falling for bastards – married men, usually – and keeps getting her heart broken when they won't leave their wives and set up home with her. Why goes that happen?'

'In my experience,' said Mrs Pargeter judiciously, 'women who always go after unsuitable men do so because deep down they don't really want to commit themselves.'

'Huh,' said Joyce. 'Well, I just wish Conchita'd settle down and get married.'

'Why? Do you really think marriage is the perfect solution?'

'I don't know. I just think life is generally a pretty dreadful business and maybe it's easier if there are two of you trying to cope with it.'

This seemed to Mrs Pargeter an unnecessarily pessimistic world-view. She had never regarded life as an imposition, rather as an unrivalled cellarful of opportunity to be relished to the last drop. Probably it was just bereavement that had made her friend so negative.

'I don't know, though,' Joyce went on, digging herself deeper into her trough of gloom. 'How much do you ever know about other people? I mean, you think you're close, you live with someone, sleep with them for twenty-five years, then they die and you realise you never knew them at all. I don't think you ever really know anything about another person.'

This made Mrs Pargeter think. It did not make her question her own marriage – she had never doubted that she and the late Mr Pargeter had known each other through and through – but it did make her ask herself how much she knew about Joyce Dover.

The answer quickly came back – not a great deal. Mrs Pargeter had met Joyce some fifteen years before in Chigwell, during one of those periods when the late Mr Pargeter had had to be away from home for a while. Joyce's husband, Chris, it transpired, was also away at the time (though on very different business), and she and their daughter Conchita, then a tiny black-eyed six-year-old, were living in a rented house till his return. The two women had seen a lot of each other for three months, and kept in touch intermittently since.

Though there was a ten-year age difference between them, they had got on from the start, without ever knowing a great deal about each other's backgrounds. Joyce, Mrs Pargeter was told, had always lived in London. Her husband Chris had been born in Uruguay, but, politically disaffected with the governing regime, had fled to England in his late teens. He had made a success of some kind of export business (dealing chiefly with Africa) and had, from all accounts, turned himself into the perfect English gentleman. His origins were betrayed only in details like his daughter's unusual Christian name. That was all Mrs Pargeter had ever known about the life and business of Chris Dover.

And she had seen to it that his wife Joyce knew even less about the life and business of the late Mr Pargeter.

Joyce maundered on, but Mrs Pargeter only half-listened. The retsina was as welcome as ever, and in the soft, warm breeze that flowed off the sea, lulled by the recorded strumming of bouzoukis, she started to relax. It had been a tiring day, and the prospect of a lethargic fortnight in the sun became very appealing. There was always, Mrs Pargeter found, something seductive about being in a new place. So many exciting details to find out when you start from total ignorance. Yes, she was going to enjoy herself in Agios Nikitas. Very relaxing, she thought, to be in a place where I know no one, and no one knows me.

Which was why she was so surprised to hear a voice saying, 'Ah, good evening. Mrs Pargeter, isn't it . . . ?'