Mrs Midnight and Other Stories (4 page)

Read Mrs Midnight and Other Stories Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

I had rung Jill naturally, and she seemed delighted by the news coverage.

‘I’m beginning to think you’re a bit of a star too,’ she said.

‘You are too kind, Miss Bennett.’

‘By no means, Mr Darcy.’ That was progress.

I discussed with her the television feature on the Old Essex and the Ripper suspect that I was arranging for the Local London TV News and the possibility of a full-length documentary. Three days later Jill, Crispin and I were down at the Old Essex with a camera crew. I had specially asked Crispin to come along as our ‘architectural expert’, which pleased Jill.

Once again it was raining, but not as heavily as the last time. We decided to film indoors first and wait for it to clear to do the establishing shots outside in the street. I did my stuff to camera about this wonderful old building and how it was steeped in the rich history of the East End, and then Crispin did his architecture bit. I wasn’t going to tell him that his material was bound to end up on the cutting room floor. He wasn’t bad, but he was too fond of his own voice.

Then there was a lightening in the rain so Jill and the crew went out to do the establishing shots. Crispin and I voted to stay indoors and drink the skinny lattes the P.A. had got us from the nearest Starbucks.

So there we were, the two of us, alone in the auditorium of that great dirty old Cathedral of Sin. It was so quiet; you could almost hear the dust falling through the shafts of grey light. Somewhere in the deep distance traffic rumbled in a twenty-first century street, but it was miles and ages away. Crispin started to look at me very intently, so I looked back at him. He was not bad looking, I suppose, in a rather girly way, with his shoulder length blonde hair and his pretty mouth. The looks won’t last, though, I thought. I’m dark with good cheekbones. I may be forty, but I’m built to last. I go to the gym.

‘You really are a little shit,’ he said. I was astonished, but I said nothing. Crispin went on. ‘You may as well know; you haven’t a chance with Jill. She is, as you would say, “out of your league.” You do realise that, don’t you?’

He was expecting me to react, to say something, but I didn’t. I just went on staring at him. He reckoned without the fact that I didn’t get where I am today without being a bit of a psychologist. After a pause, he started up again, but not quite as confident as before.

‘I know all about your efforts to impress her. Visits to the British Library; dinners at gastro-pubs, tickets to that truly ghastly show of yours. It won’t do you any good, you know. She isn’t remotely interested in you, never will be, and shall I tell you why—? Good God, what’s that?’

‘What?’

‘Didn’t you see it? Some sort of flicker of light, there on stage, just behind the pros arch.’

No. Nothing. Then, yes, there

was

something. By the proscenium arch, I saw a yellow light flicker, like a candle flame. Someone was holding a lighted candle on the stage. Then it began to move and we saw the outline of the thing that carried it. It was a big old woman with a long dress and a shawl over her head. Her back was to us. She looked like a huge huddled heap of old clothes. Slowly she began to shuffle away from us upstage.

‘Excuse me!’ said Crispin, in his best public school prefect voice. He was talking loud and slow as if to an idiot child. ‘Excuse me, I don’t know who you are, but I don’t think you’re supposed to be here. This is a listed building, you know! Excuse me!’

Then he started to move towards the stage.

‘Christ, where are you going?’ I said.

‘I want to know what the hell’s going on,’ he said. ‘Come on!’ I couldn’t stop him, so I just followed.

He climbed up onto the stage and I warned him about the floorboards. Dammit, there was a great hole in the middle of the stage; but he ignored me and I climbed up after him.

It was a funny thing. That great shambling lump of an old woman kept ahead of us the whole time as we threaded our way over piles of junk and rubble. We weren’t able to catch up with her, but she was always in our sight. It was almost as if she were leading us somewhere. Crispin called out to her several times, but she simply did not react. She shambled on with her flickering candle.

When she got to the back of the stage she turned right and went through a narrow brick archway. There was now no light apart from the candle and our torches. Once through the archway we were in a backstage corridor. It was all brick, black with age or fire. To our right was a stone staircase up which we could see a flicker of candle and hear the heavy footsteps of the old woman ascending, accompanied by long groaning breaths.

Surely now we could catch up with her, so we plunged up the dirty, lightless stair, barely considering now what we were doing or why.

At the top of the steps we found ourselves in another dim, black brick corridor. And we were amazed to see that the old woman, now practically bent double and so headless to us, was halfway along it, about twenty yards ahead, hobbling away. We shouted at her, but on she went regardless.

The corridor smelt of something oily and old, and when I touched the wall by accident a black tarry substance stuck to my hand.

At last we were beginning to catch up with the woman when she suddenly stopped in a viscous looking puddle, turned and then started to climb yet another staircase to her right. When we arrived at the bottom of this flight we heard her steps cease and saw that she had halted ten steps up, her back to us. The groaning breaths were beginning to sound like some dreadful kind of singing. I thought I could recognise some words of the old Music Hall song:

Why am I always the bridesmaid,

Never the blushing bride?

Ding dong, wedding bells,

Only ring for other gells . . .

With little shuffles she was turning slowly round to face us, and I knew now that my worst fears would be confirmed. As she moved she let the plaid shawl slip from her head to reveal a greasy white cranium planted with wild tufts of white hair, sprouting like winter trees in frost on a barren landscape. Half of her face I had seen before. There was the heavy brow, the wild grey eye, the great blob nose, the thick mannish chin, but the other half was a mangled mess, an angry chaos of fiery scar tissue, utterly unrecognisable as a face at all. Mrs Midnight lifted the candle to his head so that we could see it all.

Why am I always the bridesmaid,

Never the blushing bride . . . ?

Then he hurled the candle down the stairs towards us. I thought it would extinguish itself in the oily pool at the bottom of the steps. But it did not. It guttered for a moment, then a great tongue of flame leapt up from the pool and began to lick at Crispin’s jeans. There was a roar and the next minute he was engulfed in flame. I took off my jacket and tried to smother the fire, but he was screaming and fighting me off. The only thing to do was to hurry him back down the corridor which was now spitting little gobs of flame from every tarry crevice. Before we had reached the stairs leading down to the stage, Crispin collapsed. First I beat out the fire on his body with my jacket, then picking him up in a fireman’s lift I carried him downstairs. Behind me the flames were roaring like an angry ghost.

I had got down onto the stage level with Crispin on my back. I thought we were home safe so I began to run across the stage, but I had forgotten how rotten the boards were. There was a crack and suddenly we were falling into a pit. Crispin broke my fall a little, but I felt a sharp pain in my shoulder and one leg appeared to be useless. We were in the dark. I could see nothing, but there was a reek of corpses all around us.

I had a mobile in my pocket and was able to summon help

. They told me later that Crispin and I had tumbled into a cellar where they had also found a large number of dead cats in various stages of decomposition. What was odd, they told me, was that so many of the cats had suffered injuries to the head. Some of them looked as if the tops of their skulls had been surgically removed. I did not want to know.

I had broken several bones in my body and needed a couple of operations, so I wasn’t going to be pushed out of the hospital in a hurry as usually happens. I’m afraid Crispin was rather worse off. As well as other injuries, the fire had burned the beauty out of half his face. I genuinely feel bad about that.

I have a private room at the hospital, of course. In the evenings Jill, my angel, comes to see me with grapes or something else I don’t really want, but I feel better for her coming. I want to say something to her so much, but I can’t because I’m frightened of being turned down, rejected.

Get off! We want the bingo, not you, yer boring boogger!

And then, just recently, I have woken up in the early hours of the morning to find the great bulk of Mrs Midnight crouched by my bed. From the folds of the plaid shawl Mrs Midnight will take a kitten, still alive and mewing, and out of its trepanned head Mrs Midnight will scoop a quiver of grey jelly with a teaspoon.

‘This is your brain food,’ says Mrs Midnight. ‘Eat up!’

COUNTESS OTHO

5th December 1987

I loathe fans. I realise I shouldn’t be saying this. The correct thing for actors to say is that fans are the lifeblood of the theatre: we love and respect them. No, we don’t. I’m not talking about theatregoers; I’m talking about the people who hang around the stage door and ask for your autograph. These come in two categories. There are the ones who lie in wait for you as you come out after the show and demand that you sign their stupid programmes when all you want to do is go for a drink. These are bad enough, but at least they have been to see the show.

No, the people I really despise are the ones I call the Book People. They are there as you arrive at the theatre before the show, and they will almost never actually buy a ticket for it. Unless you are famous they will ignore you, but if you are they will fawn. They are the ones who carry books. Sometimes these are simple autograph books, big oblong items bound in gaudy leatherette, but the really sad ones carry huge books of actor’s directories with photographs in them, and they want you to sign below the pictures. When they are not trying to extort autographs they are comparing notes and twittering with each other about whose signature they’ve got, and whom they haven’t managed to trap. They are the train-spotters and the twitchers of the show-business world.

The Book People belong to a distinct physical type. They are men and women, nearly always undersized, with sticky, intense little faces, unwashed hair and hungry eyes. The greasy anorak or the worn brown duffel coat are their traditional modes of dress. They are vampires: they feed off the spilt blood of celebrity. They warm their stunted little bodies in the reflected sunlight of fame.

I mention them because they have begun to put in an appearance outside the stage door. This is situated in a little passage that runs between the Strand and Maiden Lane. It is a dingy and depressing alley. If you found it in Whitechapel or Soho you might expect to find a dead prostitute propped up against a wall, her eviscerated guts spilling onto the pavement, like rotten fruit bursting out of an old paper bag.

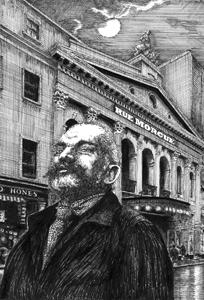

Where was I? Yes, the Book People have arrived already in our preview week. If the show fails they will no doubt all disappear which will be some small consolation. I don’t know now whether it will be a hit or not. When I am rehearsing for a show I nearly always come to believe that it is the best thing ever: it is only when performances begin that a sense of detachment reappears. A musical called

Rue Morgue

, set in Paris, featuring a number of Poe’s stories and indeed Poe himself—though, as far as I know, he never visited Paris—may fall between two stools. It may be too highbrow for the general, and too populist for the critics. The music is good Lloyd Webberish stuff and the star rather improbably playing Poe is Ricky Dee, plucked from the celebrity of a Boy Band called, for no obvious reason, Stiletto. He’s not as bad as one might have feared, but I am understudying him, as well as playing the small part of the banker Mignaud. If he breaks a leg or loses his voice I will go on in his part and I will be much better than him.

Meanwhile the Book People are all over Ricky Dee and I pass into the theatre unnoticed.

8th December

The first night went well and the critics liked it.

Rue Morgue

is a hit and the crowd of creeps around the stage door increases in number.

A parcel arrived for me in the post from my older brother Vincent who is a solicitor. With it a letter from him:

Dear Bro,

As you know, when Great Aunt Cecily died in October, she did not leave much, as she was in a Home. All the same I had a hell of a job sorting out her affairs. There was no money to speak of, but she left me the few sticks of furniture she still had. Knowing your interest in things theatrical—hope your little play is going well, by the way—she left you all her papers and scrap books. I will send these on later. In the meanwhile I send you this. I found it in a secret compartment of the escritoire. It appears to be a parcel, addressed to her, but unopened. It might, I suppose, be of interest or even some value. Anyway, it’s your pigeon. You deal with it.

All the best, etc.

Vincent.

This is a typical Vincent letter, careless, condescending, implying that he does all the work and I do nothing. He does not even call me by my name, just ‘Bro’ which I’ve always hated. An ill-disguised contempt for the stage and theatre people lurks in the background. Mention of the escritoire was another thing that annoyed me. It is a genuine Louis XVI piece and I had always admired it. I thought Great Aunt Cecily was going to leave it to me, but I expect Vincent got round her when he was visiting the Home and pretending to manage her affairs. I did not see her as often as I would have liked in her last year because I was on tour.

Cecily had been an actress in her youth and was over a hundred when she died. She gave up professional acting in the late twenties when she married a military man. It was a happy marriage by all accounts but there were no children. To the last she retained a love of the theatre, so she and I had a lot in common. I was very fond of her, and I thought she was fond of me, but all I have to show for it are a few scrapbooks and an unopened parcel. This is Vince’s doing.

For some reason I decided to take the parcel with me unopened into the theatre and beguile the useless moments when I was off stage by studying the contents in my dressing room. This evening as I was going in through the stage door I heard someone say:

‘Ye have it with ye?’

The voice seemed to come from the little huddle of Book People who stood by the door. I felt sure that the words were addressed to me. It was a strange accent to hear in London: lowland Scottish at a guess, thick, uneducated. I stared at the Book People and they stared back with mean, uncomprehending expressions. Then two of them at the back of the crowd began to bicker about something.

‘All right! You don’t have to push. There’s no call for that.’

‘I was not pushing you thank you very much.’

‘Excuse me, but are you calling me a liar?’

‘I’m sorry but I do not push. I do not push people. I don’t know who pushed you, but, I’m sorry, it wasn’t me.’

I left them, still squabbling in their little hell.

It was not until the interval that I got round to the parcel. It had been sent from the United States to England and the postmark was dated 1918, day and month illegible. It had been elaborately done up in brown paper with string and sealing wax, and I had to borrow a knife from the Assistant Stage Manager to open it. Inside was a loose folder containing over a hundred sheets of hand-written manuscript. On the folder itself was written in a painstaking round hand:

Countess Otho, a drama in four acts by Richard Archer Prince

.

It was a play. Clipped inside the cover of the folder was a typewritten letter on company notepaper.

Sammons Plays Ltd, for the Finest in Today’s Drama,

303 W 57th St. NY. U.S.A.

December 19th 1918

My Dear Cecily,

On May 17th this year our mutual friend Mr William Abingdon came to the offices of my publishing house in West 57th Street to discuss the MS of

Countess Otho

which he had left with me some days previously. I told him that the work was certainly a curiosity, but that my firm published plays of proven merit and not curiosities. Had I known that Mr Abingdon was so down on his luck I would have given him something for his pains, but, as soon as he heard my verdict he went away without even giving me the opportunity of returning the MS. As you know, he committed suicide the following day. No one seems to want it, so I send it to you, because you have an interest in such things and because you knew some of the folk connected with this little curiosity.

As a tribute to our former friendship.

Jacob R. Sammons.

I could make nothing of this, or for that matter, of the play which was hand-written on various sheets of paper, some lined and torn out of a cheap exercise book, some headed with the addresses of provincial hotels. The writing itself was variable. It was an uneducated hand but parts had been written with great care and neatness; other parts, particularly those on unlined hotel notepaper, were erratic and barely legible scrawls.

My cue was called over the Tannoy. The effort of reading only a few lines had exhausted me and I decided to postpone further study of it until tomorrow. I have left the manuscript in the theatre.

15th December

I have not had time to write for several days. Things have happened. There was a cold snap, black ice on the streets, even in the Strand. In Maiden Lane five days ago Ricky Dee slipped, fell and smashed his hip. Now he’s in hospital and can’t move. There was a tremendous fuss because he claimed he’d been pushed. Luckily I could prove that I was nowhere near or they might have suspected me, I suppose. So, being his understudy, I went on for him as Poe. I have had to put on this ridiculous moustache, otherwise it’s fine. Of course the management is already talking about a ‘name’ to replace him, or rather me, but they may be thinking better of it. People have been saying great things about my performance and no-one has asked for their money back at the box office. There have been jokes about a ‘lucky break’ for me, but I can take it. It’s all good publicity.

Yesterday when I had finished the big number ‘Dark Streets of my Mind’, the audience cheered and clapped for what seemed like several minutes. I have stopped the show. It was strange: I found that my eyes had filled with tears and all I could see was a spangled web of coloured light, purple-orange, blue-green from the floods and spots shining down on me. I was wrapped round with light and applause, and for a moment the world stopped pinching.

Outside before the show I have been signing things for the Book People. No, I haven’t changed my mind about them. They’re still losers. The other day while I was signing I heard that voice again with the thick Scottish accent.

‘Have ye read it yet?’

‘Who said that?’ I said, but the BPs looked blank. They just shook their greasy little heads and kept thrusting their filthy biros into my hand to write for them. There was someone else in the crowd, behind the rest. He was dark and hung back, unlike the others, and he looked more like a tramp, but it was dark so I couldn’t see properly.

18th December

Now, I’m into my part and I have done all the interviews and running around associated with being the latest star, I have had time to have a look at

Countess Otho

. I keep it in my dressing room, and sometimes I come in early to study it. It’s like a hobby.

Of course as a play it’s utterly hopeless, written by a complete no-talent, probably a madman of some kind.

The plot is only intermittently comprehensible, but it seems to reflect the turn-of-the-century vogue for Ruritanian Romance.

The Prisoner of Zenda

published in 1894 began it all. It concerns a Princess Sar, rightful heiress to the throne of Adelphia (sometimes spelt Adelfia) who is tricked into marrying the evil Count Otho. Otho is a plausible villain: and only the Countess sees through his mask of virtue. ‘To others he is a god,’ she says at one point, ‘but I see only a sink of shattered turds.’ On the King’s death, Count Otho usurps the throne. In order to regain power and exact revenge, the Countess, like Hamlet, pretends to be mad. Count Otho wants to put her away for good, but cannot do so before her madness has been established in open court. ‘Countess Otho’ triumphantly proves her sanity and, at the moment of victory, stabs the Count to death. This bloody act brings the play abruptly to a close.

I think I have made

Countess Otho

sound more accessible than it really is. Much of it is more dull than strange. Large chunks of it have quite obviously been lifted from other plays and clumsily transposed. The only glimmerings of talent or originality occur in the scenes in which the Countess is feigning insanity. One speech sticks in my mind because of its suggestion of theatrical imagery. I have corrected the spelling which is appalling throughout, though in some parts it has been corrected by another hand.

COUNTESS OTHO: The worm squeals on the dunghill. All the sky is blotted out. The wind and the rain are blotted out. The sea is blotted out. The houses are flat. The trees and mountains are flat. The little hills have been put into the scene dock, and the brook is starved of water. The fairy daggers of the stars have been put into the property cupboard. I have walked on and I have seen what is behind, and it is nothing. You call me mad? Mad? You will hear of my madness. The whole world will ring with it.