Mrs. Kennedy and Me: An Intimate Memoir (26 page)

Read Mrs. Kennedy and Me: An Intimate Memoir Online

Authors: Clint Hill,Lisa McCubbin

Tags: #General, #United States, #Political, #Biography, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Politics, #Biography & Autobiography, #United States - Officials and Employees, #20th century, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Onassis; Jacqueline Kennedy - Friends and Associates, #Hill; Clint, #Presidents' Spouses - Protection - United States, #Presidents' Spouses

I stood close to Mrs. Kennedy as they presented the dagger and she accepted it graciously.

What the hell do they think she is going to do with a dagger?

I thought.

Then they brought out the lamb, all dressed in a colorful silk costume. She touched it on its nose and then thanked them for their thoughtfulness as the tribal chieftain led the animal away.

I hurried Mrs. Kennedy into our car, and as we started back onto the winding road to the Khyber Pass, I could hear the poor animal bleating as it was sacrificed in her honor.

As we progressed over the winding mountain roads, armed tribesmen and members of the Khyber Rifles, the Pakistan army’s paramilitary force responsible for securing the border, escorted us. It was a crystal clear day and you could see for hundreds of miles across the rugged terrain that formed the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Our convoy was being carefully watched throughout our journey to the Khyber Rifle outpost, and off in the distance, at various intervals, I could discern men with rifles standing guard as we passed the various checkpoints. The Pakistan government wanted to make sure that nothing would happen to mar the visit to the Khyber Pass.

We drove through the town of Torkham, to the border separating Pakistan and Afghanistan, to the Khyber Pass, where the Pakistan and Afghanistan military faced each other eyeball to eyeball. It was here that the Khyber Rifles maintained control. Looking out from this point at the Hindu Kush mountains, one can feel the presence of Genghis Khan and his horde of Mongol tribesmen as they rode through these mountains. The soldiers of Alexander the Great had passed this way, and based on the number of blue-eyed people we saw along the way, it was apparent they had left descendants behind.

Mrs. Kennedy was wearing the cap President Ayub Khan had given her, and I was sure it was the first time anyone had ever worn the cap with a tailored jacket, skirt, and pumps.

Mrs. Kennedy commented on what a beautiful sight the view was and we then went to Landi Kotal, the headquarters of the Khyber Rifles, to have lunch at the Khyber Rifles Mess. Ron Pontius and I exchanged glances when they brought out a big platter of roast lamb—thankfully not the same animal that had been presented as a gift a few miles back.

Our last night in Pakistan was spent back in Karachi and there was one last thing Mrs. Kennedy wanted to do. The year before, Vice President Lyndon Johnson had visited Pakistan and made a big deal out of meeting a camel cart driver named Bashir, whom he had stopped to shake hands with by the side of the road. In typical LBJ fashion, the vice president casually remarked, “Why don’t y’all come see me sometime?” Bashir accepted the invitation, and the friendship between the American vice president and the Pakistani camel cart driver turned into a media spectacle as Bashir toured the United States and became an overnight celebrity.

Mrs. Kennedy had brought a letter from Vice President Johnson and wanted to personally deliver it to Bashir. So it was arranged for Bashir to bring his family and his now famous camel to visit her at the president’s residence in Karachi, with the full ranks of press in attendance.

Of course the press wanted a photo of Mrs. Kennedy with Bashir and the camel. They were snapping away like mad when Mrs. Kennedy suddenly turned to Bashir and asked, “May we ride your camel, Bashir?”

Oh dear God.

Riding the camel was not in the program. Mrs. Kennedy and Lee were both wearing knee-length sleeveless dresses with high heels—not exactly camel-riding attire—and I thought,

that’s all we need is for you to fall off a camel with the press catching it all on film.

Bashir looked nervously at the president’s military aide for permission. Then the military aide turned to me. “What do you think? Is it okay, Mr. Hill?”

Mrs. Kennedy and Lee were laughing and having such a good time, I thought, what harm can it do?

“If Mrs. Kennedy wants to ride the camel, go ahead and let her ride the camel,” I said.

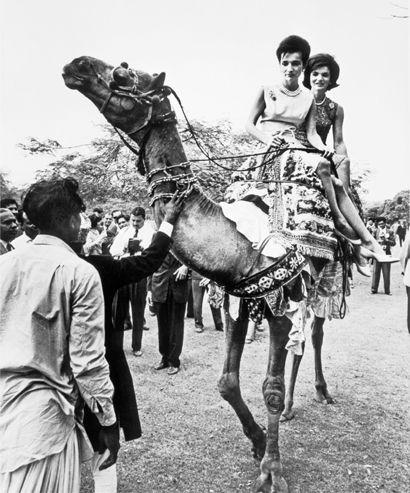

So Bashir got the camel to kneel, and while Lee required some assistance getting on the camel’s back sitting sidesaddle, Mrs. Kennedy turned her back to the camel, put her hands on the saddle, and effortlessly hoisted herself up. Sitting side by side, Lee and Mrs. Kennedy were just laughing and laughing. But this wasn’t enough for them. No, they wanted to ride the camel, not just sit on it.

“Up, up!” Mrs. Kennedy said as she motioned with her hands to Bashir. “Make him stand up!”

Bashir was so nervous he was sweating. He knew that a camel does not get up very gracefully and with the two women sitting sidesaddle, they were perched rather precariously on the camel’s back. He looked at me again, and I nodded.

“Go ahead,” I said.

As the camel slowly got up—first its back legs, and then its front legs—I called out to Mrs. Kennedy, “Hold on!”

So there they were high atop the camel, Lee in front and Mrs. Kennedy at the back, laughing and just having the best time as the photographers were snapping away like crazy. Bashir led the camel around at a slow pace, and then Mrs. Kennedy said to Lee, “Hand me the reins, Lee.”

Fortunately Bashir did not let go of the lead, and despite Mrs. Kennedy’s best efforts to get the camel to take off in a gallop, Bashir retained control.

I stood there and watched with amusement, not saying a word, as Mrs. Kennedy laughed and laughed.

T

HE TRIP TO

India and Pakistan had been tremendously successful for Mrs. Kennedy personally as well as politically. Ambassador McConaughy would write a note to President Kennedy expressing the enormous impact she had: “She has won the confidence and even the affection of a large cross section of the Pakistani populace who feel that they know her and know that they like her. I believe benefits to our relations with Pakistan will be reflected for a long time in ways intangible as well as tangible.”

André Malraux and Marilyn Monroe

Mrs. Kennedy and André Malraux at White House dinner

T

he trip to India and Pakistan had truly been an adventure and Mrs. Kennedy couldn’t stop talking about it. For three days, she stayed in London, at Lee and Stash Radziwill’s posh townhouse at No. 4 Buckingham Place, not far from Buckingham Palace, and while there was one official visit with Queen Elizabeth, mostly it was meant to be a few days of relaxation before returning to the United States.

Mrs. Kennedy and Lee regaled Stash with stories of their adventures, and when Stash would be disbelieving about something, Mrs. Kennedy would turn to me and say, “Tell him, Mr. Hill. Didn’t it happen just as we said?”

She seemed to recall every detail of every fort and palace she had visited, and was still in awe over the magnificent Islamic architecture, the splendor of the Taj Mahal, the opulence of the Indian president’s residence. During one of these conversations, I must not have responded in the way she expected to something she had said, because she suddenly turned to me and asked teasingly, “Doesn’t anything ever impress you, Mr. Hill?”

I remember looking at her lounging on the sofa in casual slacks, a cigarette in her hand, laughing, so relaxed with her sister and Stash. I wanted to say, “You know what impresses me, Mrs. Kennedy? You. Everything you do impresses me. The way you handle yourself with such grace and dignity without compromising your desire to enjoy life and have fun. You don’t even realize the impact you have, how much you are admired, how you just single-handedly created bonds between the United States and two strategic countries far better than any diplomats could have done. And you did it just by being curious and interested and sincere and gracious. Just by being yourself. No politics. No phoniness. Just you being you.”

But I was there to do my job, and my job did not entail saying things like that to her. So all I said was “I guess it takes a lot to impress me, Mrs. Kennedy.”

W

HEN WE RETURNED

to Washington on Thursday, March 29, the president was waiting at Washington National Airport to greet Mrs. Kennedy. There were lots of press and it was a heartwarming homecoming. As it turned out, Sardar had not yet arrived, but arrangements had been made for the horse to be delivered on a Military Air Transport Services (MATS) plane a couple of weeks later. Somehow President Ayub Khan had convinced someone to allow Sardar’s trainer to accompany the horse on the long journey, with specific instructions not to leave Sardar until he was delivered to Mrs. Kennedy. So when Sardar showed up at Andrews Air Force Base in the middle of the night, poor General Godfrey McHugh, President Kennedy’s military aide who had been charged with handling the rather delicate arrangements, was in for quite a shock when the trainer, all decked out in his military attire—the red jacket with brass buttons, white jodhpurs, boots, and turban—got off the plane with the damn horse.

When we returned from the India and Pakistan trip, it was back to our normal routine of Middleburg on the weekends, with Mrs. Kennedy returning to the White House for special functions.

After ten days in Palm Beach for Easter, we returned to the White House the day before another historic dinner honoring Nobel Prize winners from the Western Hemisphere. Impressive as it was to host forty-nine Nobel laureates in her home, Mrs. Kennedy was far more concerned with and excited about a dinner two weeks later honoring André Malraux, the French minister of culture.

While many Americans might not have been familiar with Malraux, he was one of Mrs. Kennedy’s idols, and she had become enamored with him during her trip to Paris the year before. Malraux had led an extraordinary life: he was an adventurer/explorer, a Spanish Civil War veteran, a World War II resistance leader who had escaped from a Nazi prison, and had served in the de Gaulle administration since its inception. But Mrs. Kennedy, with her degree and interest in French literature, knew him best for his prizewinning writings.

Malraux had escorted Mrs. Kennedy through several Paris art museums during the 1961 trip, and even though I was merely on the sidelines at the time, there seemed to be a strong connection between the two of them as they chatted comfortably together in French. Tish called their relationship a mutual “intellectual crush” and that, I think, summed it up perfectly. During one of our many discussions about the Paris trip Mrs. Kennedy said, “Mr. Malraux is so interesting. He has been everywhere, knows everyone, and has done so many things. He is a real hero of France.” Mrs. Kennedy wanted this dinner to be the most special one yet, and the guest list was the top priority.