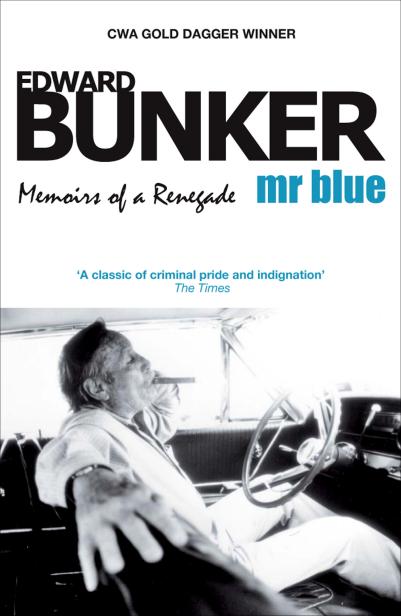

Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade

Read Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade Online

Authors: Edward Bunker

Mr Blue

Memoirs of a Renegade

Contents

In March of 1933, Southern California suddenly began

to rock and roll to a sound from deep within the ground. Bric-a-brac danced on

mantels and shattered on floors. Windows cracked and cascaded onto sidewalks.

Lath and plaster houses screeched and they bent this way and that, much like a

box of matches. Brick buildings stood rigid until overwhelmed by the

vibrations; then fell into a pile of rubble and a cloud of dust. The Long Beach

Civic Auditorium collapsed with many killed. I was later told that I was

conceived at the moment of the earthquake and born on New Year's Eve, 1933, in

Hollywood's Cedar of Lebanon hospital. Los Angeles was under a torrential

deluge, with palm trees and houses floating down its canyons.

When

I was five, I'd heard my mother proclaim that earthquake and storm were omens,

for I was trouble from the start, beginning with colic. At two, I disappeared

from a family picnic in Griffith Park. Two hundred men hunted the brush for

half the night. At three I somehow managed to demolish a neighbor's back yard

incinerator with a claw hammer. At four I pillaged another neighbor's Good

Humor truck and had an ice-cream party for several neighborhood dogs. A week

later I tried to help clean up the back yard by burning a pile of eucalyptus

leaves that were piled beside the neighbor's garage. Soon the night was burning

bright and fire engine sirens sounded loud. Only one garage wall was

fire-blackened.

I remember the ice-cream caper and fire, but the other

things I was told. My first clear memories are of my parents screaming at each

other and the police arriving to "keep the peace." When my father

left, I followed him to the driveway. I was crying and wanted to go with him

but he pushed me away and drove off with a screech of tires.

We lived on Lexington Avenue just east of Paramount

Studios. The first word I could read was

Hollywoodland.

My mother was a chorus girl in vaudeville and Busby

Berkeley movie musicals. My father was a stagehand and sometimes grip.

I don't remember the divorce proceedings, but part of

the result was my being placed in a boarding home. Overnight I went from being

a pampered only child to being the youngest among a dozen or more. I first

learned about theft in this boarding home. Somebody stole candy that my father

had brought me. It was hard then for me to conceive the idea of theft.

I ran away for the first time when I was five. One

rainy Sunday morning while the household slept late, I put on a raincoat and

rubbers and went out the back door. Two blocks away I hid in the crawlspace of

an old frame house that sat high off the ground and was surrounded by trees. It

was dry and out of the rain and I could peer out at the world. The family dog

quickly found me, but preferred being hugged and petted to raising the alarm. I

stayed there until darkness came, the rain stopped and a cold wind came up.

Even in LA a December night can be cold for a five-year-old. I came out, walked

half a block and was spotted by one of those hunting for me. My parents were

worried, of course, but not in a panic. They were already familiar with my

propensity for trouble.

The

couple who ran the foster home asked my father to come and take me away. He

tried another boarding home, and when that failed he tried a military school,

Mount Lowe in Altadena. I lasted two months. Then it was another boarding home,

also in Altadena, in a 5,000 square foot house with an acre of grounds. That

was my first meeting with Mrs Bosco, whom I remember fondly. I seemed to get

along okay although I used to hide under a bed in the dorm so I could read. My

father had built a small bookcase for me. He then bought a ten-volume set of

Junior Classics, children's versions of famous tales such as

The Man without a Country, Pandora's Box

and

Damon and Pythias.

I learned to read with these

books.

Mrs Bosco closed the boarding home after I had been

there for a few months. The next stop was Page Military School, on Cochran and

San Vicente in West Los Angeles. The parents of the prospective cadets were

shown bright, classy dorms with cubicles but the majority of cadets lived in

less sumptuous quarters. At Page I had measles and mumps and my first official

recognition as a troublemaker destined for a bad end. I became a thief. A boy

whose name and face are long forgotten took me along to prowl the other dorms

in the wee hours as he searched pants hanging on hooks or across chair backs.

When someone rolled over, we froze, our hearts beating wildly. The cubicles

were shoulder high, so we could duck our heads and be out of sight. We had to

run once when a boy woke up and challenged us: "Hey, what're you

doing?" As we ran, behind us we heard the scream: "Thief!

Thief!" It was a great adrenalin rush.

One night a group of us sneaked from the dorm into the

big kitchen and used a meat cleaver to hack the padlock off a walk-in freezer.

We pillaged all the cookies and ice-cream. Soon after reveille we were

apprehended. I was unjustly deemed the ringleader and disciplined accordingly.

Thereafter I was marked for special treatment by the cadet officers. My few

friends were the other outcasts and troublemakers. My single legitimate

accomplishment at Page was discovering that I could spell better than almost

everyone else. Even amidst the chaos of my young life, I'd mastered syllables

and phonetics. And because I could sound out words, I could read precociously —

and soon voraciously.

On

Friday afternoons nearly every cadet went home for the weekend. One weekend I

went to see my father, the next to my mothers'. She now worked as a coffee shop

waitress. On Sunday mornings I followed the common habit of most American

children of the era and went to the matinee at a neighborhood movie theater. It

showed double features. One Sunday between the two movies, I learned that the

Japanese had just bombed

P

earl Harbor. Earlier, my father had declared: "If

those slant-eyed bastards start trouble, we'll send the US Navy over and sink

their rinky-dink islands." Dad was attuned with the era where

nigger

appeared in the prose of Ernest Hemingway,

Thomas Wolfe and others. Dad disliked

niggers,

spies, wops

and the English with "their goddamn king." He

liked France and Native Americans and claimed that we Bunkers had Indian blood.

I was never convinced. Claiming Indian blood today has become somewhat chic.

Our family had been around the Great Lakes from midway through the eighteenth

century, and when my father reached his sixties he had high cheekbones and

wrinkled leather skin and looked like an Indian. Indeed, as I get older, I am

sometimes asked if I have Indian blood.

At Page Military School, things got worse. Cadet

officers made my life miserable, so on one bright California morning, another

cadet and I jumped the back fence and headed toward the Hollywood Hills three miles

away. They were green, speckled with a few red-tiled roofs. We hitchhiked over

the hills and spent the night in the shell of a wrecked automobile beside a

two-lane highway, watching the giant trucks rumble past. Since then that

highway has become a ten-lane Interstate freeway.

After shivering through the night and being hungry

when the sun came up, my companion said he was going to go back. I bid him

goodbye and started walking beside a railroad right of way between the highway

and endless orange groves. I came upon a trainload of olive drab, US Army

trucks that waited on a siding. As I walked along there was a rolling crash as

it got underway. Grabbing a rail, I climbed aboard. The hundreds of army trucks

were unlocked so I got in one and watched the landscape flash past as the train

headed north.

Early

that evening I climbed off in the outskirts of Sacramento, 400 miles from where

I started. I was getting hungry and the shadows were lengthening. I started

walking. I figured I would go into town, see a movie. When it let out, I would

find something to eat and somewhere to sleep. Outside of Sacramento, on a bank

of the American River full of abundant greenery, I smelt food cooking. It was a

hobo encampment called a Hooverville, shacks made of corrugated tin and

cardboard.

The hoboes took me in, but one got scared and stopped

a sheriff s car. Deputies raided the encampment and took me away.

Page Military School refused to take me back. My

father was near tears over what to do with me, until we heard that Mrs Bosco

had opened a new home for a score of boys, from age five through high school.

She had leased a 25,000 square foot mansion on four acres on Orange Grove

Avenue in Pasadena. It was called Mayfair. The house still exists as part of

Ambassador College. Back then such huge mansions were unsaleable white

elephants.

"Mayfair" was affixed to a brass plate on

the gatepost of a house worthy of an archduke: but a nine-year-old is

unimpressed by such things. The boys were pretty much relegated to four bedrooms

on the second floor of the north wing over the kitchen. The school classroom,

which had once been the music room, led off the vast entrance hall, which had a

grand staircase. We attended school five days a week and there was no such

thing as summer vacation. The teacher, a stern woman given to lace-collared

dresses fastened with cameos, had a penchant for punishment. She'd grab an ear

and give it a twist, or rap our knuckles with a ruler. Already I had a problem

with authority. Once she grabbed my ear. I slapped her hand away and abruptly

stood up. Startled, she flinched backwards, tripped over a chair and fell on

her rump, legs up. She cried out as if being murdered. Mr Hawkins, the black

handyman, ran in and grabbed me by the scruff of my neck. He dragged me to Mrs

Bosco, who sent for my father. When he arrived, the fire in his eye made me

want to run. Mrs Bosco brushed the incident away with a few words. What she

really wanted was for my father to read the report on the IQ test we had taken

a week earlier. He was hesitant. Did he want to know if his son was crazy? I

watched him scan the report; then he read it slowly, his flushed anger becoming

a frown of confusion. He looked up and shook his head.

"That's a lot of why he's trouble," Mrs

Bosco said.

"Are you sure it isn't a mistake?"

"I'm sure."

My father grunted and half chuckled. "Who would

have thought it?"

Though what? He later told me the report put my mental

age at eighteen, my IQ at 152. Until then I'd always thought I was average, or

perhaps a little below average, in those abilities given by God. I'd certainly

never been the brightest in any class — except for the spelling, which seemed

like more of a trick than an indicator of intelligence. Since then, no matter

how chaotic or nihilistic my existence happened to be, I tried to hone the

natural abilities they said I had. The result might be a self-fulfilling

prophecy.

I continued to go home on weekends, although by now my

mother lived in San Pedro with a new husband — so instead of switching over every

weekend, I spent three of the four with my father. Whichever one I visited, on

Sunday afternoon I would say goodbye, ostensibly returning straight away to

Mayfair. I never went straight back. Instead I roamed the city. I might rent a

little battery-powered boat in Echo Park, or go to movies in downtown Los

Angeles. If I visited my mother in San Pedro, I detoured to Long Beach where

the amusement pier was in full swing.